Japanese immigration to Pacific states began in the 1880s after anti-Chinese legislation led to a shortage of cheap labor. Labor recruiters for factories, rail roads, mining camps, fisheries and plantations looked to Japan to recruit cheap labor from abroad (Takaki 180). The rising Japanese population led to the Census Bureau creating a “Japanese” category for race, distinct from the “Chinese” race and subsequent anti-Japanese legislation was passed in the United States.

Anti-Japanese sentiments culminated with Executive Order 9066 in 1942–3 months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The order interned Japanese Americans, including those who were citizens, in camps primarily located in Mountain and MidWest states. Executive Order 9066 did not intern Japanese Americans in Hawaii.

I will analyze how the internment of Japanese Americans affected their migration patterns across the United States. I will also analyze how the citizenship status (the Nisei) of Japanese Americans affected their migration.

Data:

I am using census data from the Integrated Public-Use Microdata Series (IPUMS). I am working with 1% samples from 1900 to 1960 and 1970 (Form 1% state sample).

The 1960 and 1970 census are self-reported, mail back forms. Unlike censuses from 1870 to 1950, the 1960 and 1970 censuses are not administered by census enumerators.

I am excluding Hawaii and Alaska from my analyses because there is no Hawaii or Alaska census data for 1940 and 1950. However, I recognize that Hawaii and Alaska were important immigration destinations for Japanese immigrants. Hawaii had a very high Japanese American immigrant and citizen population and did not intern Japanese Americans during WWII.

Method:

I divide my analyses of Japanese American migration into 2 segments, Issei and Nisei migration.

Issei are 1st generation Japanese American immigrants born in Japan who were incapable of becoming American due to the 1790 Naturalization Act. The act only permitted “free white persons” to become naturalized citizens. (The Naturalization Act was amended in 1870 to naturalize Blacks born in the US.) Issei were distinctly classified as “Japanese,” not “White” in the census, denying them naturalization. The denial of naturalization for Issei was formally upheld in Ozawa v. United States (1920). The court ruled that Issei could not be white, because the Japanese were “clearly of a race which is not Caucasian,” a position upheld by the census for 30 years prior.

However, Nisei, 2nd generation immigrants born in the United States, did have American citizenship. Nisei were able to better integrate into American society because it was harder to legally discriminate against Nisei, as they were American citizens. Nisei were also better culturally integrated and had more education.

I used the IPUMS RACE variable (RACE=5) to identify Japanese Americans and then used IPUMS BPL to separate Issei (BPL=501) and Nisei (BPL<100). All analyses are weighted with the IPUMS individual sample weight PERWT variable.

I mapped the Issei and Nisei populations by STATEFIP and by YEAR. Additionally, I graphed the growth of the Japanese American population by Issei and Nisei by YEAR.

Results:

Issei immigration to the U.S. ended in 1924 after the 1924 Immigration Act banned all Asian immigration to the U.S. However, the 1924 Immigration Act was replaced by the 1952 McCarren-Walter Act, which permitted Asian immigration (with a quota based on 1920 census information). (The Mccarren-Walter Act was subsequently replaced by the 1965 Hart-Celler Act, which replaced quota based immigration with skill, refugee and family member based immigration.)

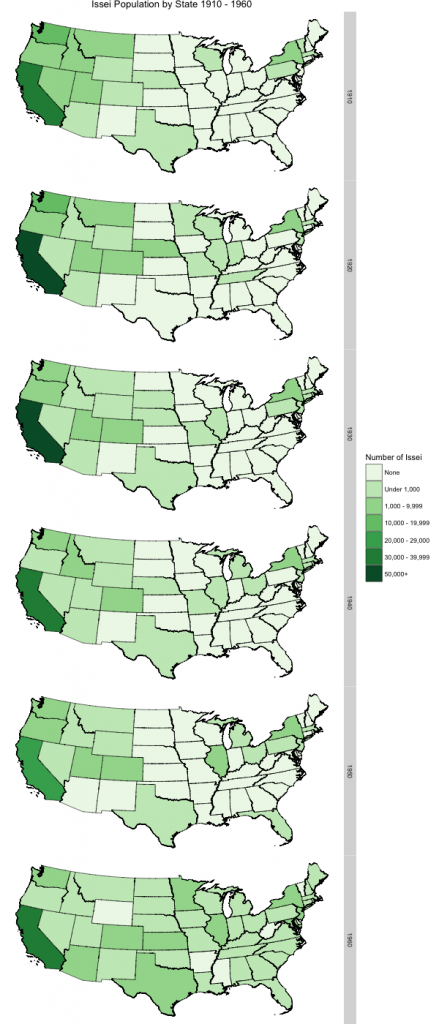

We can see Issei migration from the west to east. Issei originally immigrated to western states, then to the Middle States and then finally branched out to the Midwest in the 1940s and 1950s. The migration starts to dwindle in 1940 and 1950 most likely due to death and no new immigration. In 1960 we start to see fresh migration under the Mccaren-Walter Act. New Japanese immigrants filled in the Southern States and remaining MidWest States.

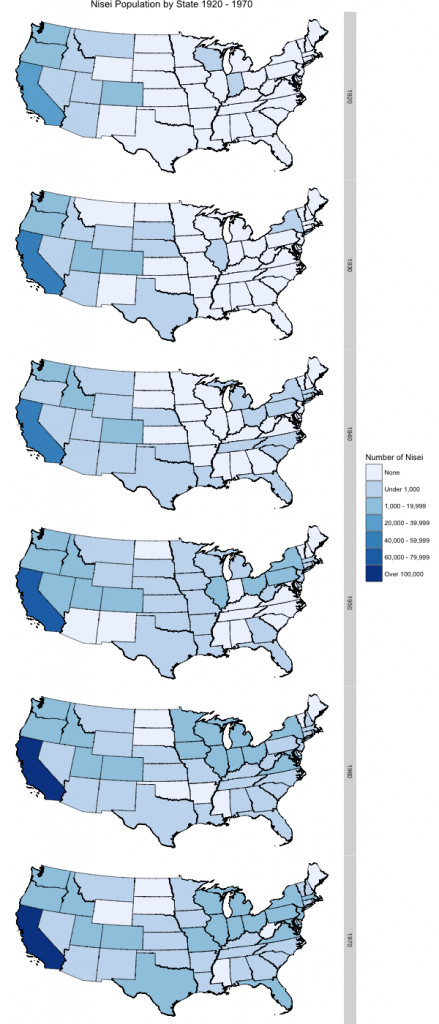

Figure 2 displays the Nisei migration from west to east. Between 1920 and 1930, Nisei begin to migrate from the Western states to the Rocky states, leaving California. This may be due to the 1920 and 1923 amendments to the California Alien Land Law which banned Nisei from owning land on behalf of their non-citizen Issei parents (Lyon).

It is important to remember that until internment, most Nisei were still dependent on their Issei parents. Many Nisei migrated with the Issei or were born in the state. Two Issei parents giving birth to five Nisei children would raise Nisei migration on the maps more than Issei migration would be raised.

The maps also show Nisei migration patterns after the internment. In 1950 we see that Nisei had moved to most of the MidWest and had already started moving to Southern states. Interestingly, Nisei also moved back to California in 1950.

Figure 3 supports my claim that the Mccaren-Walter Act and Hart-Celler Act increased Japanese immigration. It explains the increased Issei population growth across the entire US. However, the graph (and maps) does not account for Sansei, 3rd generation Japanese Americans born to Nisei parent(s). I could not find a way to separate Sansei from Nisei without using the IPUMS AGE variable. I found it to be risky to divide AGE based on my assumptions on when the generational Nisei and Sansei cutoff would be. The dramatic increase in the 1960 Nisei population is due to Sansei.

Conclusion:

Through the use of IPUMS census data we can visualize and track Japanese American migration from west to east. Anti-Japanese laws and labor discrimination forced Japanese Americans to remain concentrated in the West until the 1942 internment. After WWII and the internment, Japanese Americans, especially the well educated Nisei, were able to travel and settle in new locations. Many Nisei were offered the opportunity to leave internment camps early if they could find work or attend university in the MidWest or east coast (Digest of Points). We see this shift in the Nisei data. By 1970, Nisei had nearly been evenly spread across the US (California remained the outlier).

The graphs also display Issei migration patterns and mortality rates. Ronald Takaki notes that unlike the Nisei, the Issei, “developed a separate Japanese economy and community” in the West and most survivors returned to their Californian roots by 1950 (Takaki 180). We consistently see declining Issei population numbers until 1960, when Japanese immigration is reopened.

The data and graphs overall support my theory that the internment of Japanese-Americans in 1942 eventually led to Nisei migrating elsewhere across the U.S.–primarily MidWest and Eastern states. Many Nisei chose the MidWest because they were barred from returning to the West, usually because of racist policies of resettlement. The Alien Land Laws were not repealed until 1952 (Lyon).

Works Cited:

“Digest of Points.” Conference of Consideration of the Problems Connected with Relocation of the American-Born Japanese Students Who Have Been Evacuated From Pacific Coast Colleges and Universities. Stevens Hotel, Chicago: Occidental College Library, 29 May 1942.

Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (McCarran-Walter Act). Pub. L. 82-414. June 27, 1952.

Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 (Hart-Celler Act). Pub. L. 89-263. October 3, 1965.

Lyon, Cherstin. “Alien land laws.” Densho Encyclopedia. 23 May 2014, 22:40 PDT. 9 Feb 2016, <http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Alien%20land%20laws/>.

Takaki, Ronald. Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. New York: Little, Brown and Company, 1998.