This week established a great foundation through which we will be able to dive into the rest of the course. In opening up the conversation about what sound actually means and how we can perceive it better, the Kahn reading provided a very strong understanding of what sound means. As he explains, sound pertains to the sounds, voices and aurality that falls within the auditive phenomena, which can be wide-ranging and often beyond what we typically think of as sound. As we learn early on in the text, sound has played a crucial role in the world’s history, and yet we often fall subject to the tendency of leaving these sounds behind – forgetting about their historical significance. As such, his text aims to discover the “political, poetical, and ecological” aspects of sound that have been drowned out by us over time.

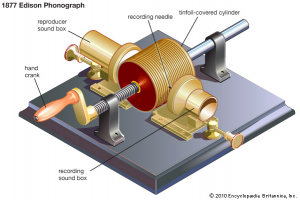

One major discussion that he brings about during his brief description of post-modern sound is the implementation and significance of the phonograph (see below):

As the reading explains, this instrument concentrates on the intersection of sound with its surroundings – the touch, the vibrations, and the living environment that defines sound art. More specifically, Kahn explains that “the book concentrates primarily on ideas of phonography, by which I mean all mechanical, optical, electrical, digital, genetic, psychotechnic, mnemonic, and conceptual means of sound recording as both technological means, empirical fact, and metaphorical incorporation…” (Kahn, 16). To me, I found this discussion to be particularly interesting, as before the introduction of this instrument by Edison in the late 19th century, we had a lack of ability to preserve sound in an anecdotal way. As Kahn explains, the phonograph opens these doors, which were fundamental in sound art as a practice.

Next, in the Handmade Electronics Reading, we were able to learn about the construction and goals behind electronic production. In general, Collins lays out five simple goals for his electronic production framework: use battery powered projects, keep things simple, keep things cheap, to design by ear (not eye), and to to learn that there is no “right way” of doing things in sound art production, so we can “forgive and forget” easily.

In the next section, Collins provides us with a simple breakdown of the various components that go into electronic music production. He runs through sections describing how to listen to your projects (which amplifiers / drivers are best), the tools that are important to have in the production process, the parts, the batteries, and the architecture of the project. Overall, this reading (similar to the Khan piece) helps use better progress our initial knowledge of the sound art practice field and the ways in which we can approach the subject in a new and unique frame of mind.

<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>*<>

Alvin Lucier: One piece that I particularly liked in Lucier’s portfolio is titled I am Sitting in a Room. In this piece, Lucier repeats the words in the title of his piece into a room while recording the output from the speaker, and as he continues to do so, we end up arriving at the room’s characteristic resonance. Through this piece, Lucier shows us that each space has its own characteristic resonance that is unique to its environment and internal surroundings. Additionally, I found his piece titled Music on a Long Thin Wire, to be interesting, as Lucier uses a a horseshoe magnet and amplifiers to induce vibrations onto a wire. To me, both of these pieces provide an understanding of how sound interacts with space and how the installation completely depends on its surroundings.

Doug Hollis also had work that I found to be very interesting – particularly because of his pieces’ interaction with the wind blowing across the surfaces of his work. For example, his work titled Aolian Harp has a 27-foot-tall harp that is essentially played by the wind blowing between its strings, resulting an an eerie orchestra of sounds played naturally by its surroundings. Similarly, he has another piece titled Zephyr Trio, which has three tall poles, each with a panel that juts out perpendicular to the vertical pole. As the wind hits these panels, sound plays through the hollow vertical poles, resulting in the sounds of an organ being played by the wind. I especially liked these pieces by Hollis becuase they rely entirely on the sculpture shape as well as the installation of the piece (in relation to it’s surrounding environment).

Overall, each of these pieces were interesting, from Tinguely’s intricate and beautiful Tinguely Fountain in Switzerland to Natasha Barrett’s We are Not Alone piece, which occasionally erupts in movement when sounds play around it, I found each piece to be telling of the ways in which sound art can respond to acute changes in environments surrounding the displays. To me, there is a very clear interaction between physical movement and noise – an awareness that I was not as profoundly aware of before viewing the functionalities and intricacies of these pieces.