To properly understand the cultural significance of Anna Cora Mowatt Ritchie, one must understand the historical context in which she wrote and performed.

American drama offered its participants no prestige. The stages were no more populated with citizens of class and esteem than the seats in the theaters. In antebellum America, it was said that “the greatest opportunity for the aspiring dramatist lay in becoming an actor or actor-manager-dramatist,”[1]. The vocation of playwright held no special place of honor, and the overwhelming majority of them were white males, churning out formulaic melodramas. The popular plays emphasized spectacle, and favored exaggerated situations over faithful depictions of reality. Actors and actresses were not accepted into the upper echelons of society, and were considered morally corrupt. The public was especially suspicious of actresses.

Why the women? “The cult of the true womanhood,” also called the cult of domesticity, had reached its peak in America during the 1860s, building in popularity since the 1830s[2]. This cult defined feminine behavior, and violators were to be shunned or shamed by all respectable members of society. A respectable woman would not to showcase her body on a stage and would not work outside of the home. She must always be pious, pure, and submissive. Even Mowatt admitted in her autobiography that “the idea of becoming a professional actress was revolting,” which explains why her first foray on the stage was not as an actress, but as an orator[3].

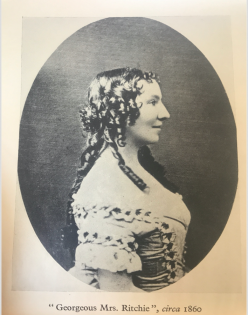

Mowatt carefully framed her reading as high-class event, only done to support her family and as a last resort. Additionally, Mowatt “further manipulated her social and gender identity vis-à-vis her self-presentation” wearing a simple costume of a plain white dress, and no adorments except a rose in her hair, and one at her bosom.[4] Her careful cultivation of her presentation ensured the protection of her reputation and allowed her to begin her career without sacrificing her honor or place in society. Later, Mowatt’s transition to the stage did still shock and awe those in her social circles, but she had laid the groundwork so that it did not cost her everything.

By the turn of the century, drama was “established as a source of entertainment, a political weapon, a means of glorifying the nation and a teacher of moral behavior,” – a starkly different environment than at the start of Mowatt’s career[5].

[1] (Meserve 42).

[2] (Macki 4).

[3] (Macki 5)

[4] (Macki 4).

[5] (Meserve 42).