The Public Good of AT&T Stadium

Abstract

This paper looks at the Dallas Cowboys’ initiative for a new stadium and how eminent domain was used to seize property for the project. In order for eminent domain to be justified, the land must be used for the “public good,” yet the Cowboys are privately owned. To determine how the Cowboys portrayed themselves as a public good, I examine local laws and politics to understand the legality of the situation. Then I examine the attitude of the media surrounding the project and how grassroots organizations resisted the initiative and were defeated. By promising a great economic improvement and using the multitude of varying business connections afforded by a strong Local Growth Coalition, Jerry Jones succeeded in using eminent domain to build a voter approved and subsidized stadium. This result reveals the ways that certain businesses influence local populations to increase their private value through governmental means.

Introduction

John Locke famously wrote that the role of a government is to protect an individual’s life, liberty and property. These beliefs became the philosophical backbone for the American Revolution, and the Declaration of Independence references these unalienable rights in its preamble. Considering these core values of the United States, the government’s power to exercise Eminent Domain seems like a modern Kafkaesque nightmare, yet in recent years authorities have increasingly evoked this process to seize private property. Eminent domain is a power that the government can evoke to forcibly take privately owned property, such as houses and businesses, in exchange for what the government determines to be just compensation, so long as the intended use of the seized land is determined to be “for the public good.” What constitutes a public good has become broader, and local governments have begun to use this power to seize privately owned lands in order to make room for huge new sports complexes. This expanded use of eminent domain foreshadows the greater muddying of the line between government and private infrastructure for companies that can demonstrate public value.

The Construction of Cowboys Stadium

In 1994, Jerry Jones, the owner of the Dallas Cowboys, looked around his 65,000 seat Texas Stadium and decided that it just was not impressive enough for his taste. He dreamed up an entertainment mega-plex that affirmed the mantra that everything is bigger in Texas. Although Jones’ net worth is right around 5 billion dollars, he looked toward local government for a hefty subsidy to help him pay for the state of the art, billion dollar stadium, as is precedent in the US when a team seeks to build a new stadium (Ozanian). Dallas, which claims the team’s location, denied Jones’ request to offer a public vote on new taxes to fund the project; they had just funded a new basketball arena and the council did not believe they could justify raising another 425 million through new taxes (Delaney 81). Undeterred, Jones canvassed local cities until he found Robert Cluck, the Mayor of Arlington, Texas, who jumped at the chance to host the new stadium, saying, “we offered them money to come here and build their stadium, we were just trying to help them out” (Kuriloff). Cluck convinced the city council to hold a vote to install new taxes in order to raise 350 million dollars to subsidize the stadium, and the residents of Arlington approved the initiative, essentially paving the way for a project that would significantly benefit the Cowboys and their owner.

In the ensuing months, construction of the stadium stagnated until the city could purchase a collection of about 150 private residences and businesses in the proposed location. Some people took the city’s initial offers, yet most held out. It was not until the Supreme Court’s 2005 ruling in Kelo v. New London that the project could move on. The ruling stated that eminent domain, the governmental seizure of private property in the name of the public good, can be used in cases in which the public good is not a specific public infrastructure, rather anything that a local area determines to be of worth to the city. In other words, the ruling broadened the definition of public good to include private enterprises. Within a day, the Mayor had announced that the town would use eminent domain in the stadium project. After the Cowboys settled with the remaining holdouts, they had space to build their 1.6 billion dollar stadium. But how were the Cowboy’s able to portray the new stadium as a public good? Why did the residents agree to new taxes and the ostentatious hassles of a billion dollar construction project for a business that could fund itself? Through an analysis of local media, laws, and corporate response to activist movements, the answer becomes clear and raises concern about the power of private businesses vicariously using government power for their private benefit.

Methods

Hyperlocalism

The big idea I will use to examine the discussion behind the construction of the new stadium in Arlington is hyperlocalism, a term that Hess defines as “the use of localized knowledge and local social networks as a source of corporate profit” (Hess 5). This can be applied to how teams in the National Football League, all of which have a local identity, generate private revenue. Because sports teams are connected with the culture of a place, many residents of that place identify with the team just as they do with the region. Even if they are not avid fans, some people still show an inclination to root for the home team if they are doing well. Just look at the lyrics of Take Me out to the Ball Game: “Root, root, root for the home team, if they don’t win it’s a shame.” The true shame is that teams often threaten to leave their city if they cannot reach a deal with the local government for a new stadium, just as the Rams did early this year (Hanzus). Teams play on the localized fear that residents have of losing a local team in order to secure funding that will generate future profits, thus exploiting the local residents for profit, a key component of Hess’ hyperlocalism. This concept can prove useful when looking at the way that teams spread pro-stadium campaigns through what Hess calls “localized networks” that involve collections of businesses that stand to benefit from large economic projects.

LGCs and Corporate Welfare

These localized networks that are the driving force behind many movements to subsidize public stadiums are called local growth coalitions, or LGCs. An LGC may seem like a local force to try improve economic justice in a region, through initiatives aimed at helping local businesses succeed; however, they almost exclusively help large corporations, essentially operating as vehicles for hyperlocalism. In his report on the media’s impact on stadium initiatives, Kevin Delaney states that growth coalitions are “dominated by corporations, real estate firms, political elites, financial organizations, and the local media”, (Delaney 73). LGCs focus on large, publicly funded projects because “land exchange values increase with development projects and thus generate profits,” (Lekakis 6). These coalitions focus on the “exchange value” of land and ignore the “use value,” thus creating a rift between local elites who benefit from the sale and development of land and the residents who use the land for less profitable ventures. Because LCGs are pervasive in many different business fields, they are often have a large influence on public perception, and this “overwhelming influence on urban affairs results in opposition” (7). In terms of eminent domain, LGCs are likely to support its use in order to raise the exchange value of the land with a new stadium, thus reducing its use value for the people who live there.

A term that references this imbalance between the residents, and speaks to the businesses that benefit from it, is Corporate Welfare. This term is an ironic phrase that parallels impoverished people and welfare with corporations and government subsidies. LGCs are often catalysts in deals that could speculatively be corporate welfare, as they use their private resources and hyperlocalism to generate public funding. The irony associated with this term is derived from the ideology of the capitalist US economy in which businesses are supposed to create success for themselves without the help of “handouts” or “entitlements,” which have become dirty words in America. In order for a business to appear thriving and healthy while still accepting governmental subsidies, they must position themselves as a public good to avoid the designation of accepting Corporate Welfare. The media proves to be an important ally for corporations to have in order to avoid the unilateral public designation of corporate welfare.

Media

The impact that local media has on the opinion of its audience is appreciable, and when it comes to a questionable public project, the media’s attitude towards it can be a determining factor in the outcome. In many places that approve stadium projects, the media organizations are involved in an LGC that is pushing for the project’s success (Delaney 76). In a study of the overall media positions of a variety of stadium initiatives, a perfect 8/8 projects went the way that the media had portrayed (positive media positions were approved, negative were denied) when LGCs focused on the stadium issue (76). In this way it can be seen how large corporations use hyperlocalism to work together to progress goals of corporate development. Even if there is no LGC with interest in the initiative, the media can step in and influence the people in a way that aligns with their political bias. As Delany notes “the media can effectively challenge these initiatives when it steps into a power vacuum left by a corporate community lacking unity” (89). For any new stadium initiative, the local media’s portrayal of the project is a key factor in deciding its ultimate fate, so examining the general attitude of the media towards a stadium initiative is a way to gain insight into the outcome of that initiative.

Kelo v. New London

In 2005, the Supreme Court made a landmark ruling that broadened the definition of what is a “public good” by allowing local governments to make the decision themselves. The case originated in New London, Connecticut, where the local government used eminent domain to give land to a real estate developer for the vague purpose of “economic development.” The residents who had been removed from their homes argued that “economic development” and “public good” were not synonymous, and led by Susan Kelo, the case made its way to the US Supreme Court. In a 5-4 decision, the Court said that “public use” was not just limited to “use by the public,” thus establishing a precedent where local governments could make their own decisions as to the extent that they would use eminent domain (Cornell Law). This decentralization favors the states and allows them to “adjust restrictions to eminent domain on the state level,” (Poirier 111). In effect, this ruling “legalized” hyperlocalism in regions where the government has a tolerant definition of public good, like The Lone Star State. In Texas, the law “does not prohibit the taking of private property through the use of eminent domain for economic development,” and it even goes further to specifically make an inclusion for “a sports and community venue project approved by voters at an election,” (Title 10). Justice Stevens justified these increased state rights in his case opinion by writing that “State courts are fully competent to adjudicate challenges to local land-use decisions,” (Poirier 118). Public entertainment meccas must be important to Texans, as their legislature has specifically allowed eminent domain to be used for the creation of stadiums, so long as it is approved by voters. This of course creates the ultimate goal for a team to portray themselves as a local good, and it sets the stage for LGCs and to push for decisions that may not be in the local residents’ best interests, emphasizing the danger of hyperlocalism for property owners.

Results

Jones’ Rhetoric and the Media

When a team requests funds for a new stadium, they often use the same argument that their new stadium will bring an economic revival to the city. It’s a compelling argument, as it’s logical that a gorgeous, new, high-tech stadium will bring people from all over to the city, causing nearby businesses to flourish. Owner’s say that a stadium will provide jobs and lift a “blighted” area to prosperity. Jerry Jones has championed these beliefs over and over, saying,

“As far as 15 years ago I’d go to the floor of the Texas Legislature and I’d say: ‘You’re not creating a subsidy to build a stadium, you’re priming the pump for people intoxicated with being involved with sports. Use them to prime the pump with private dollars, because invariably, they’ll spend more than you’d ever imagine,” (Sandomir).

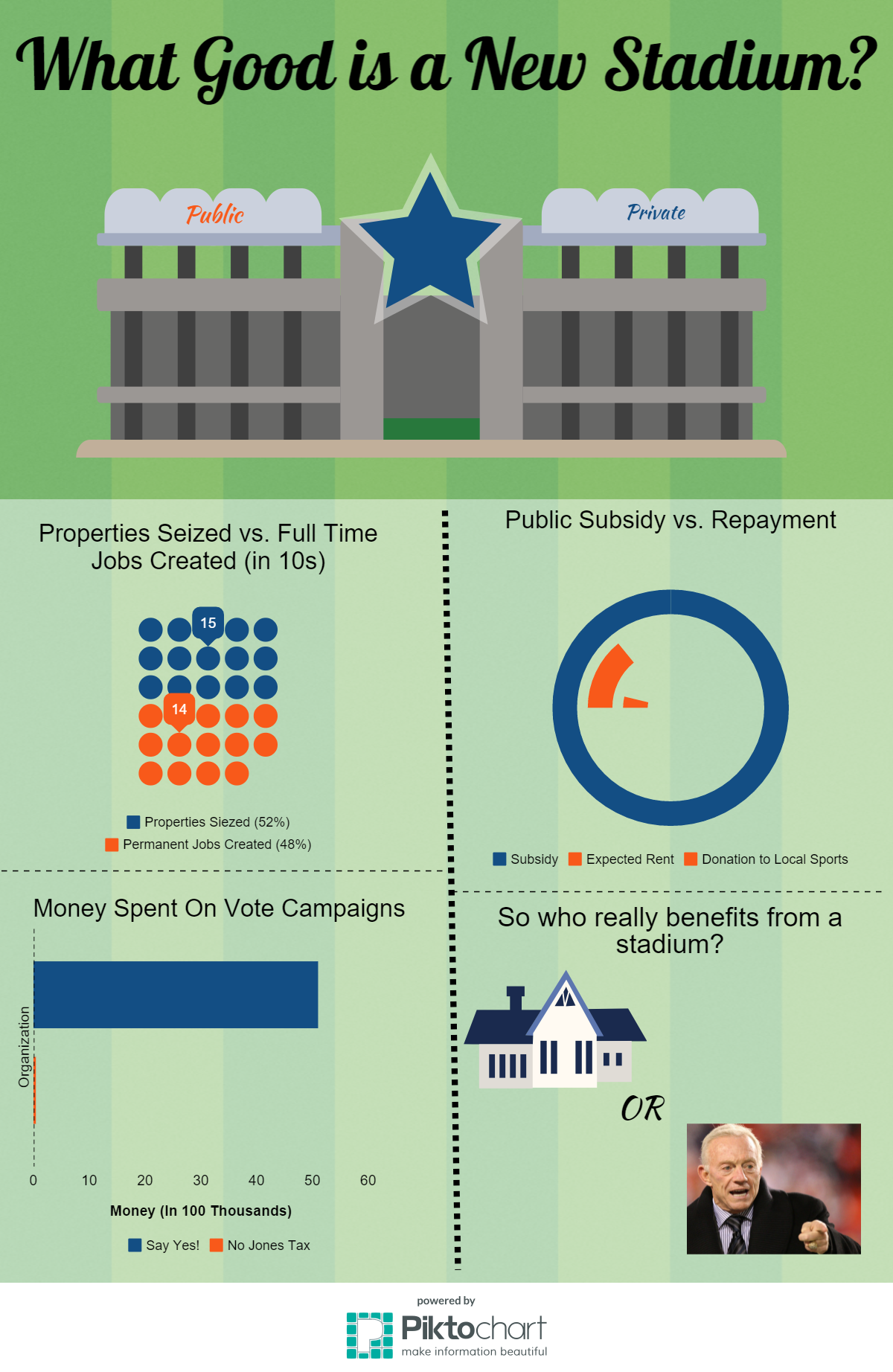

Jones argues that a new stadium will bring wealthy fans who are eager to spend money to the area, yet there is good evidence to suggest that “spending generated by a suburban-style stadium takes place inside the gates” (Korosec). According to a study that examined a large amount of research associated with new stadiums, “independent work on the economic impact of stadiums and arenas has uniformly found that there is no statistically significant positive correlation between sports facility construction and economic development (103). Much of this can be explained by the fact that public spending and lost tax revenue often exceeds the revenue generated by the stadium. When Arlington invested in the Cowboys, the revenues from naming rights, event tickets, and concession sales all went, and continue to go, directly to Jones. Jones was aware of this, yet he continued to use calculating local rhetoric, like the “Vote Yes! A Win for Arlington” campaign, to build support for his case while staying hidden from the public eye. (Ross).

Through the power of LCGs and the media, “Vote Yes! A Win for Arlington” raised over 5 million dollars in support of the new stadium initiative (Kuriloff). This may seem like a lot, however the Cowboys funded this group, and they used its local reach to spread support for the stadium. The group showcased both players and cheerleaders from the team at events, and the campaign used its large budget to “put out 10 mailers, three TV ads and have sponsored rallies aimed at various neighborhoods and minority groups,” (Korosec). They ran a highly effective operation using civic pride in the Cowboys to generate public support, even though their plan had negative effects on the communities that would be taken away for the stadium’s land. These communities emphasize the tension between the exchange value that the Cowboys offered for the land, and the use value that residents had raised through the strengthening of their community over time. For someone who has lived in the same place for many years, that place becomes worth more than the actual value of the land; it holds memories, familiarity, and a sense of community that is not intrinsically factored into the price of a property. This makes it hard to part ways for some seemingly arbitrary amount of money that a real estate agent proposes. This was the case for Paul Jordan, an Arlington resident who lost his home he said “It’s one of those rare neighborhoods that you don’t often find that had a sense of community, I knew everyone around me on a first-name basis.” (WFAA).

Compared to the 5 million dollars in support of the stadium, the opposition group, “No Jones Tax Coalition”, raised only 43,000 dollars, and when faced with opposition funding that high and a media that worked against them, their chances of influence were low (Ross). The Arlington media enforced a pro-stadium bias by selectively covering events that aligned with their beliefs. They “failed to give any legitimacy to a fairly substantial grass-roots campaign against the stadium deal”, and thus “the framing of this initiative was clearly tilted toward stadium advocates through selective presentation and omission of facts and opinions” (Delaney 81). The Arlington media used their power to support the Cowboys, and suppress opposition, echoing a common problem in which “local elites exert an overwhelming influence on urban affairs” (Lekakis 7). Knowing that the Arlington media was part of a larger LGC, and the importance of the media’s position, Jones spent millions of dollars on the campaign, because money talks and the residents listen.

Eminent Domain Takings and the Mayor

In addition to the money that Jerry Jones pumped into campaigns to generate positive air around the initiative, he needed a political ally to support his hyperlocalist plans, and he found that ally in the mayor of Arlington. Mayor Robert Cluck supported the project through and through from its inception, and he made sure that the Cowboy’s had everything they needed. He encouraged the city council to approve the subsidy vote and he promoted the Cowboy’s at every chance he had. Of the subsidy he said “I think it’s an investment by the owner here, I don’t look at it at all as if it’s corporate welfare,” (Ross). Others vehemently disagreed, a local lawyer said that Cluck “sold out and the council went right along… we don’t provide basic infrastructure, yet we subsidize a team.” (Sandomir). And this is not just any team, the Dallas Cowboys are the most valuable franchise in the world, which means they could have easily funded the stadium themselves (Ozanian). Jones knew that the subsidy bordered on corporate welfare, so he choose to personally stay out of the lime light. The campaign, according to the head of the public relations firm in charge of it, was “100 percent about how America’s team can help make Arlington America’s City,” but there is no economic data to support that stadiums make cities better than before (Ross). Jones guaranteed an economic revival, however in exchange for the 325 million dollar subsidy, the Cowboys only promised to pay 60 million dollars in rent over 30 years and donate 16.5 million dollars to youth sports (Ross). And the promised jobs that a new stadium produces? A typical stadium only employs around 100 full time employees that work when there is no event (Siegfried 106). By keeping himself out of the public eye, Jones mitigated any concerns of corporate welfare and kept the initiative focused on garnering local support. Some people caught on, one resident believed that “Jones has taken the part of the welfare queen in this deal… the money we give him is going to go in his pocket” (Ross). The hyperlocalist campaign conquered these resistors with platform that focused on the theoretical local good that their stadium would bring.

Discussion

When the Dallas Cowboys set their sights on a new stadium in Arlington, Texas, there existed a small community on the land that they had picked to locate their football and entertainment mecca. With Kelo v. New London paving the way for local regulations on eminent domain, the Cowboys only needed to portray themselves as a public good to begin eminent domain procedures. They used hyperlocalism to achieve this. Through a strong local growth coalition, Jerry Jones convinced the residents of Arlington that the project was an economic engine, despite the widespread results that prove otherwise. The media, which had a role in the LGC, supported Jones and built up a positive attitude around the project, which in turn influenced the voters to approve a subsidy for the project. This approval did not solely provide monetary funds, it also allowed the city, headed by a zealous mayor, to evoke eminent domain in accordance with the laws of Texas. When the dust finally settled, the Cowboys that had a brand new stadium that generated corporate revenue, while the owners of 150 properties were forced to relocate.

As much as Americans love rooting for their local sports teams, they better hope that their team does not want a new stadium. History dictates that the team will threaten to leave the area if they do not receive a large subsidy for a new venue, a venue that- will generate huge revenues for the owner. If they do get the subsidy and they choose to build on developed land, there is a precedent that if all the factors fall into place, they can use hyperlocalism to gain voter approval and legally evoke eminent domain. This result is scary because it proves that any private infrastructure project may gain the legal right to take privately owned land for their private revenue. Hyperlocalism is especially successful if a corporation has the support of local politicians and media outlets. Kelo v. New London gives corporations the ability to act with the force of local government, provided that federal laws are interpreted with leniency at the local level. In the case of sports teams, a city’s fear of losing their team results in stadium deals that disguise private revenue with public good. With regard to stadiums, the only thing more magical than a young kid’s first time inside, are the reasons it is there in the first place.

Works Cited

10: General Government, Http://www.statutes.legis.state.tx.us/Docs/GV/htm/GV.2206.htm §§ 2206. Eminent Domain-001-157 (2015).

Delaney, Kevin, and Rick Eckstein. “Local Media Coverage of Sports Stadium Initiatives.” Journal of Sport and Social Issues. Sage Publications, 2008. Web. 31 Jan. 2016.

Hanzus, Dan. “Rams to Relocate to L.A.; Chargers First Option to Join.” NFL.com. National Football League, 12 Jan. 2016. Web. 05 Feb. 2016.

Joyner, James. “Eminent Domain Ruling Affects Dallas Cowboys Stadium.” Outside the Beltway. The Dallas Morning News, 25 June 2005. Web. 31 Jan. 2016.

“KELO V. NEW LONDON.” Cornell Law. Cornell Law, 22 Feb. 2005. Web. 31 Jan. 2016.

Korosec, Thomas. “Cowboys Take on Conservatives over Stadium.” Houston Chronicle. Hearst Newspapers, 18 Oct. 2004. Web. 18 Feb. 2016.

Kuriloff, Aaron, and Darrell Preston. “In Stadium Building Spree, U.S. Taxpayers Lose $4 Billion.” Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg, 5 Sept. 2012. Web. 31 Jan. 2016.

Lekasis, Nikos. “The Politics of PAO’s New Football Stadium.” IRS.sagepub.com. Sage, 4 Jan. 2014. Web. 31 Jan. 2016.

Ozanian, Mike. “The Most Valuable Teams in the NFL.” Forbes. Forbes Magazine, 14 Sept. 2015. Web. 09 Feb. 2016.

Poirier, Mark R. “Federalism and Localism in Kelo and San Remo.” Private Property, Community Development, and Eminent Domain. Ed. Robin Paul Malloy. Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate, 2008. 101-31. Print.

Ross, Bobby, Jr. “In Fight over Proposed Cowboys Stadium, Some Ask: Where’s Jerry?” MyPlainview.com. My Plainview, 31 Oct. 2004. Web. 31 Jan. 2016.

Sandomir, Richard. “A Texas-Size Stadium.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 16 July 2009. Web. 31 Jan. 2016.

“Settlement of $325,000 Ends Land Acquisition for Cowboys Stadium.” WFAA. Tegna, 16 Oct. 2009. Web. 31 Jan. 2016.

Siegfried, John, and Andrew Zimbalist. “The Economics of Sports Facilities and Their Communities.” JSTOR. American Economic Association, 2000. Web. 31 Jan. 2016.