As the Islamic State gains control over vast amounts of territory in the Middle East in hopes of creating a caliphate, it is becoming an increasing threat to the region, and potentially to the United States (Michek and Misztal). According to an overview given by the Bipartisan Policy Center, the radical jihadist organization, formed in 2000, has accrued an estimated 17,000 fighters (Michek and Misztal). A small, though significant, number of these fighters are citizens of the United States and several European nations (Michek and Misztal). Investigation into how and why Westerners are joining ranks with ISIS has revealed the group’s unprecedented ability to use various social media channels to disseminate recruitment and propaganda material. A post on the Brookings Institute blog written by Javier Lesaca, a visiting scholar to George Washington University, elaborates, “Analysis of the digital audiovisual campaigns released by ISIS since January 2014 suggests that ISIS has established a new kind of terrorism, using marketing and digital communication tools not only for ‘socializing terror’ through public opinion as previous terrorist groups did, but also for making terror popular, desirable, and imitable.” Their success in this regard, particularly on Twitter, has raised enough concern that efforts to combat their online presence are taking shape on several fronts, led by governmental organizations and hackers alike. The U.S. government has launched a program through the State Department to respond directly to pro-ISIS tweets. Hackers have flagged sympathetic accounts for suspension, flooded their most popular hashtags with spam, and monitored the communications between members to screen for information relevant to homeland security. Whether these methods have been effective against ISIS activity is a source of much contention and is the topic of exploration in this literature review.

The efforts of the United States government against ISIS on Twitter began in 2011, when President Obama signed an executive order establishing the Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications (CSCC) as a subset of the State Department. Judson Berger, a Fox News correspondent covering national security, quoted an official from the department itself as saying it hopes to offer “alternate perspectives to the misguided ideological justifications for using violence” through its Think Again Turn Away Twitter campaign. Since its launch, the account has tweeted in the English language roughly 11,000 times to over 25,000 followers. In a Think Progress article by Hayes Brown, a former contractor at the Department of Homeland Security, former State Department official Will McCants explains that these tweets constitute an effort to overlay the radical Islamic material on the site and “blunt the recruitment pitches online.”

Though most scholars believe confronting ISIS using of social media online is crucial, there exists doubt as to the value of the State Department’s Twitter campaign. Rita Katz, director of the SITE Intelligence Group for studying online extremist behavior, conducted a thorough examination of the methodology employed by Think Again Turn Away and views the program as deeply flawed. The Twitter account is designed to act in two ways: by directly engaging with pro-ISIS accounts, or trolling and by tweeting counter-material (Katz). Katz goes so far as to call the first method of engaging extremists on Twitter “ridiculous.” Her complaints center on the fact that each Think Again Turn Away tweet responding to ISIS propaganda provides Jihadists a platform to further articulate their ideas. Perhaps the most egregious example of these blunders occurred on August 6, 2015, when Think Again Turn Away responded to a tweet from a pro-ISIS account called Amreeki Witness, stating “IS has flaws, but the moment you claim they cut off the heads of every non-Muslim they see, the discussion is over” (Katz). Though the tweet was not addressed to the State Department, Think Again Turn Away tweeted back, “#ISIS tortures, crucifies & shoots some- ISIS also gives ultimatums to Christians: convert, pay or die- Some flaws u say?” (Katz). A lengthy “series of rebuttals” followed, providing Amreeki Witness a stage to expound on radical views. Katz explains, “The Think Again Turn Away account, instead of ignoring the claims of a pro-IS jihadist, dignified them by responding.” By engaging in “petty” Twitter wars with this and other similar accounts, the U.S. State Department is lending legitimacy to low-level Jihadists and aiding the promulgation of their extremist sentiment (Katz).

Due to the account’s numerous inaccuracies concerning the second method of disseminating counter-material, several sources in addition to Katz express a similarly negative sentiment. According to Joshua Keating, an international affairs reporter for Slate, Think Again Turn Away has tweeted several stories based on flimsy evidence or containing false information since its inception (Keating). One such example is a May 12, 2015 tweet providing a link to a story about forced female circumcision of two million women in Mosul, Iraq (Keating). The story was already one-year-old at the time, but beyond its lack of timeliness, the claim it makes had already been refuted by several journalistic sources in the area (Brown). Samuel Oakford, the UN correspondent for VICE News, cites a similar incident as further evidence of the account’s inaccuracy. On May 11, 2015, Think Again Turn Away tweeted an unconfirmed British tabloid article stating that girls kidnapped by ISIS frequently commit suicide (Oakford). Keating argues that by circulating stories like these that are untrue, the State Department is damaging its own credibility. Additionally, he suggests that highlighting atrocities perpetrated by ISIS, even when based solidly in fact, is at best harmless and at worst “may be selling points rather than deterrents for prospective ISIS members.”

Some content on the Think Again Turn Away Twitter feed may, however, have a positive impact. For example, Keating argues that a story posted about a young woman from the UK who came to deeply regret her decision to join ISIS once confronted with the extreme violence of the group could conceivably deter potential new members from joining with its powerful appeal to emotion. The State Department account also regularly tweets about acts of extreme violence and brutality perpetrated by ISIS, as well as information regarding successful counter-measures. Just after the recent ISIS attack on Jakarta, Indonesia, the account tweeted about the successful arrests of several terrorists involved in the attack and retweeted a message with the trending Indonesian hashtag #KamiTidakTakut, meaning “we are not afraid” (@ThinkAgain_DOS). In Brown’s article, McCants is also quoted as saying, “at least this way, we’re offering some American perspective and shooting down some of the more egregious examples.” Though Keating notes that measuring just how much hope inspired by these tweets is impossible, McCants puts forward that simply making available non-extremist perspectives is valuable in and of itself.

Other, non-official efforts to staunch the spread of extremist ideology are also taking place on Twitter. Many vigilante hackers have taken up patrol, searching for accounts of ISIS sympathizers, recruiters and fighters. Rick Gladstone, a frequent reporter for the New York Times foreign desk, explains that once found, the names of suspected accounts are broadcast via blacklists on the hackers’ own accounts. This is meant to encourage other Twitter users to report the accounts for violations that would serve as grounds for suspension or deletion by Twitter, including graphic violence and threats (Gladstone). According to an article written for the International Business Times, an in-depth digital global news publication, many hackers are moving away from lone-wolf status and are becoming affiliated with organizations like Anonymous, GhostSec and CntrlSec, all of which have taken up arms within the past year against ISIS online (Cuthbertson). The same article quotes a spokesperson for GhostSec as having said, “To date our operations have met with resounding success…We have terminated over 57,000 Islamic State social media accounts that were used for recruitment purposes and transmission of threats against life and property” (Cuthberston). This movement began when Jihadists began posting gruesome photos of beheadings and picked up speed after many hackers became outraged by the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris (Gladstone).

The activity of ISIS on Twitter, however, suggests that the group has not taken these measures lying down. Lists of hackers are circulated in the group’s Twitter circles to aid in evasion and users are encouraged to switch account handles if they suspect they’ve been reported (Gladstone). A study conducted by Recorded Future CTO and geopolitical intelligence writer Staffan Truvé raised concerns that the thousands suspensions are a drop in the bucket compared to the estimated 60,000 accounts that openly support the radical group (Truvé). The data from the study suggests that once an account is shut down by Twitter after being reported, a new account with a similar handle is promptly created and promoted by many other ISIS supporters (Truvé). New extremist content is then rapidly circulated within the vast network of sympathizers (Truvé). Based on this evidence, the study concludes that Twitter cannot keep up with the pace at which ISIS is able to expand and rebuild its network on the site (Truvé). Due to the evasive action taken by ISIS on Twitter, Gladstone is similarly unwilling to ascribe success to the rash of account terminations.

Besides simply being ineffective, the pro-ISIS account suspensions may produce measurable negative effects. “The ISIS Twitter Census,” a study by J.M. Berger and Jonathon Morgan of the Brookings Institute, demonstrated that the suspension of these accounts has caused the ISIS Twitter network to become “more internally focused.” This means that as the network continues to face outward pressure, its supporters will interact more exclusively with each other and less with people outside the network (Berger and Morgan). The study explains the effect this could have as follows: “there is a risk that the more focused and coherent group dynamic could speed and intensify the radicalization process” (Berger and Morgan). This potential outcome of the demonstrated internalization of pro-ISIS accounts, however, requires further research to be considered conclusive.

Contrary to the findings of Truvé and the reservations of Gladstone, material from “The ISIS Twitter Census” also suggests that The Twitter suspensions are creating several positive effects. By monitoring thousands of accounts affiliated with ISIS, the authors of the study estimate that 10% of the online activity of the extremist group is currently devoted to recouping the damage done to their network by mass suspensions (Berger and Morgan). This figure was calculated by considering only the frequency of the promotion of new accounts (Berger and Morgan). It did not include time spent discussing the suspensions or developing recovery strategy, both of which would contribute to an even larger amount of time spent rebuilding (Berger and Morgan). One of the hackers working to carry out the suspensions, @TheDoctor, agrees, “Basically our work not only cripples their ability to spread propaganda, but also wastes their time” (Gladstone). ISIS themselves referred to the suspensions as “devastating” and stress the importance of creating replacement accounts in a document circulated by supporters (Berger and Morgan). The study also noted that several of the suspended accounts were maintained by “some of the most active and effective users in the network” (Berger and Morgan). These suspensions detract from ISIS’ ability to recruit members and spread propaganda by forcing them to create replacement accounts and recover followers (Berger and Morgan). Despite ISIS’ efforts to rebuild, the Brookings study suggests that suspensions are “outpacing the number of new accounts successfully created, possibly by a wide margin” (Berger). The number of new accounts created after a string of suspensions in September of 2014 dropped considerably, though the suspensions continued to increase in number (Berger and Morgan).

Beyond the examination of account suspension and replacement, the Brookings study also investigated the prevalence of the most common hashtags used by ISIS. The most popular hashtag, the name of ISIS in Arabic, was tweeted 40,000 times a day when suspensions began in September (Berger and Morgan). By February, it was being tweeted fewer than 5,000 times a day (Berger and Morgan). This may be due to the efforts of hacktivists who commandeer ISIS hashtags by incorporating them into their own anti-ISIS messages, which are tweeted at five times the rate of the pro-ISIS tweets containing the same hashtag, making the ISIS messages less visible (Berger and Morgan). One example of this is cited by Mark Molloy, Social Media Content Editor at the Telegraph. The effort, nicknamed #RickRollDaesh, consisted of many Anonymous members tweeting hyperlinks to seemingly pro-ISIS material that actually led to a video of Rick Astley’s “Never Gonna Give You Up,” thwarting the ability of ISIS to use their usual hashtags to their advantage for a time (Molloy).

Besides simply working toward the suspension of pro-ISIS Twitter accounts, hackers monitor the content featured on the accounts in hopes of uncovering valuable intelligence. The BBC Trending blog, which covers on world news and why it matters, reports that one group in particular, GhostSec, has broken off from Anonymous because they felt its members had insufficient counter-terrorism experience to monitor ISIS’ online presence in a meaningful way (Wendling). One member of GhostSec, DigitaShadow, claims the group prevented a repeat terrorist attack on the island of Djerba in Tunisia by intercepting messages on Twitter between ISIS members referencing a suicide bomber in a densely inhabited area near the Homut Souk market (Cuthbertson). Though some of the Tweets existed for only minutes before being deleted, vigilant GhostSec hackers caught them and passed along the information to Michael Smith of the Kronos Advisory, a security consultant group. Smith then forwarded the threats to the appropriate authorities (Wendling). According to DigitaShadow, this information led to seventeen arrests (Cuthbertson). The group also has said it played a role in foiling an Independence Day attack in New York (Cuthbertson). Though it is difficult to verify the claims made by GhostSec, Djerba was revealed to be on a list of ISIS targets in July of 2015 and ten arrests were made in New York leading up to the July 4, 2015 holiday, indicating that the group’s measures have been met with some success (Cuthbertson).

Though the nature of online communities can make it difficult to gauge the effects of the multitude of measures being taken by the United States government and hackers against ISIS on Twitter, it can be said that different methods have been greeted with varying levels of approval. The State Department’s Think Again Turn Away was condemned as not only ineffective, but harmful and damaging to the reputation of the United States. It is possible, however, that some content on the account creates a sense of hope and helps demonstrate the atrocity of the Islamic State organization. The evidence behind methods employed by hackers against ISIS suggests they may be more successful that the Think Again Turn Away account. By monitoring furtive Twitter messages, GhostSec helped prevent at least one terror attack. And evidence suggests that the mass suspensions carried out on Twitter are decreasing the capacity for the ISIS accounts to spread propaganda and recruitment material. There exists, however, no broad determination of the overall success of efforts against the presence of ISIS on Twitter, leaving much to the unknown.

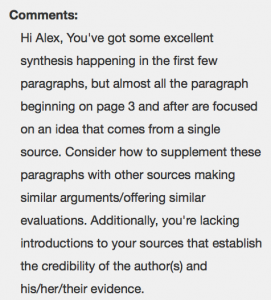

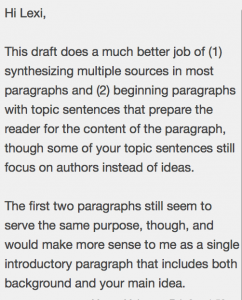

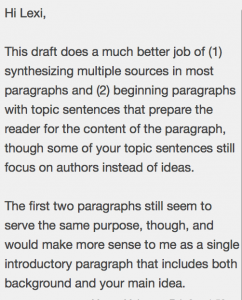

Note: This is a revised version that addresses these comments.

Works Cited

Berger, J.M. “Social Media Crackdown Hits ISIS Supporters.” CNN. Cable News Network, 2 Apr. 2015. Web. 16 Jan. 2016.

Berger, J.M., and Morgan, Jonathon. “The ISIS Twitter Census: Defining and Describing the Population of ISIS Supporters on Twitter.” The Brookings Project on U.S. Relations with the Islamic World (n.d.): n. pag. Brookings Institution. Web. Mar. 2015.

Berger, Judson. “State Department Enters Propaganda War with ISIS.” Fox News. FOX News Network, 09 Sept. 2014. Web. 21 Jan. 2016.

Brown, Hayes. “Meet The State Department Team Trying To Troll ISIS Into Oblivion.” ThinkProgress RSS. Center for American Progress Action Fund, 18 Sept. 2014. Web. 16 Jan. 2016.

Brown, Hayes. “No, ISIS Isn’t Ordering Female Genital Mutilation In Iraq.” ThinkProgress RSS. Center for American Progress Action Fund, 24 July 2014. Web. 21 Jan. 2016.

Cuthbertson, Anthony. “Anonymous Affiliate GhostSec Thwarts Isis Terror Plots in New York and Tunisia.” International Business Times RSS. N.p., 22 July 2015. Web. 16 Jan. 2016.

Gladstone, Rick. “Behind a Veil of Anonymity, Online Vigilantes Battle the Islamic State.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 24 Mar. 2015. Web. 16 Jan. 2016.

Katz, Rita. “The State Department’s Twitter War With ISIS Is Embarrassing.” Time. Time, 16 Sept. 2014. Web. 16 Jan. 2016.

Keating, Joshua. “The U.S. Government’s Anti-ISIS Twitter Account Is Full of Tabloid Garbage.” Slate. The Slate Group, 12 May 2015. Web. 16 Jan. 2016.

Lesaca, Javier. “On Social Media, ISIS Uses Modern Cultural Images to Spread Anti-modern Values.” Brookings. The Brookings Institution, 24 Sept. 2015. Web. 21 Jan. 2016.

Molloy, Mark. “RickRolled: Anonymous Use Rick Astley in War against Terrorism.” The Telegraph. Telegraph Media Group, 25 Nov. 2015. Web. 25 Jan. 2016.

Michek, Jessica, and Misztal, Blaise. “An Overview of ISIS and the U.S. Response.” Bipartisan Policy Center. N.p., 25 Sept. 2014. Web.

Samuel Oakford (@samueloakford). The US State Department is tweeting unsubstantiated articles from British tabloids about Yazidi suicides:. May 11, 2015, 4:26 PM. Tweet.

Think Again Turn Away (@ThinkAgain_DOS). Indonesians show #resilience on social media after #JakartaAttacks w/ hashtag #KamiTidakTakut (We are not afraid). January 15, 2016, 4:20PM. Tweet.

Truvé, Staffan. “ISIS Jumping from Account to Account, Twitter Trying to Keep Up.” Recorded Future. N.p., 03 Sept. 2014. Web. 16 Jan. 2016.

Wendling, Mike. “Ghost Security Group: ‘Spying’ on Islamic State Instead of Hacking Them.” BBC News. BBC Trending, 23 Nov. 2015. Web. 16 Jan. 2016.