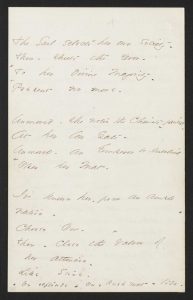

The Soul selects her own Society –

Then – shuts the Door –

To her divine Majority –

+Present no more – +Obtrude

Unmoved – she notes the Chariots – pausing –

At her low Gate –

Unmoved – an Emperor be kneeling

+ Opon her Mat – +On [her] Rush mat

I’ve known her – from an ample

nation –

Choose One –

Then – close the – +Valves of +lids

her attention –

Like Stone –

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in Packet XIII, Mixed Fasciles, ca. 1862. First published in Poems (1890), 26, from the fascicle copy (A), with the alternatives for lines 3 and 4 adopted. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

This is a touchstone poem about selection and choice in Dickinson’s canon and it has been read and much debated. Helen Vendler does a close reading of the poem, comparing it to “Of all the Souls that stand Create” (F 279), which, she argues, recounts in “unsurpassable” terms the soul’s “eschatological” or timeless and eternal choice of one person. Here, she thinks, Dickinson redoes the topic “in humbler terms.”

One place to start is with the form. The poem begins each stanza with long lines followed by very short ones, which sets a pattern of extension and truncation that feels like something being shut down or out. The first two stanzas begin with pentameter lines followed by short lines of dimeter (two feet each). The thirds stanza starts with a nine syllable line followed by a monometer (one foot line). Attention is getting shorter and shorter. In this last stanza, the monomter lines contaib spondees, two stressed syllables that bang shut with a double thump. Annie Finch observes that the poem

retreats from its initial iambic pentameter line, a movement that metrically parallels the poem’s verbal description of self-reliance and frugality.

The word “valves” with its variant of “lids” suggests an exclusion that resembles blindness and suffocation. The final rhyme of “One” and “Stone” reinforces the sense of rigidity, especially in how the first word is enclosed in the second.

In reading this poem, many readers invoke Emerson’s notion of self-reliance and his advocacy of retreating into the soul in search of the divine. Emily Budick suggests the poem

borrows linguistic trappings from Puritan theology and applies them to the phenomenon of Transcendentalism.

Notable is the theme of royalty in the “Chariots” that pause at the soul’s humble abode, and the “Emperor” found kneeling upon the soul’s lowly door mat. It is also important to note that in the third stanza, the speaker differentiates herself from this discerning “soul,” or speaks about herself in the third person–how discriminating!

Sources:

Budick, E. Miller. “When the Soul Selects: Emily Dickinson’s Attack on New England Symbolism.” American Literature 51.3 (Nov. 1979): 349-63, 352.

Finch, A. R. C. “Dickinson and Patriarchal Meter: A Theory of Metrical Codes.” PMLA 102.2 (Mar. 1987): 166-76, 172-3.

Vendler, Helen. Dickinson: Selected Poems and Commentaries. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University, 2010, 187-190.