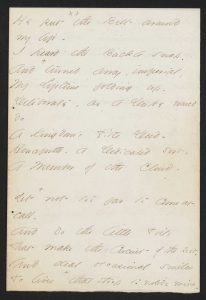

He put the Belt around

my life –

I heard the Buckle snap –

And turned away, imperial,

My Lifetime folding up –

Deliberate, as a Duke would

do

A Kingdom’s Title Deed –

Henceforth – a Dedicated sort –

A Member of the Cloud –

Yet not too far (Yet near enough) to come at

call –

And do the little Toils

That make the Circuit of the Rest –

And deal occasional smiles

To lives that stoop (As stoop) to notice mine –

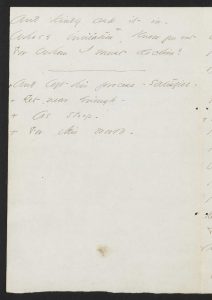

And kindly ask it in –

Whose invitation (For this world –) know you not

For Whom I must decline?

Link to EDA manuscript. Originally in: Packet XIV, Mixed Fascicles, written in ink, ca. 1860-1862. First published in Poems (1891). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass.

The word “Master” does not occur in this poem, but the speaker attributes many of the characteristics of power and domination to the “He” who snaps the belt around her life. He is “imperial,” like a “Duke” handling “a Kingdom’s Title Deed.” Marianne Noble observes:

Evident in Emily Dickinson’s writing is a strain of masochistic expression, as the first lines of many poems (“Bind me, I still can sing”; “Joy to have merited the pain”; “He put the belt around my life / I heard the Buckle snap”) and countless other phrases (“Most I love the cause that slew me,” “a Bliss like Murder”; “an ecstasy of parting / denominated Death”) suggest.

Noble connects this masochistic strain to Dickinson’s letters, especially the Master letters. But is this belt a wedding ring, or a sign of spiritual vocation, like “The Collar” of a priest or minister that gives the title to a poem by George Herbert (1593-1633) about his resistance to his religious calling. Or is it a sign of artistic calling that binds the speaker to a powerful Muse figure and keeps her separate from ordinary society? Or all three?

Joan Kirkby finds many analogs in the periodicals Dickinson read for what she calls her “bride poems,” including “poems of sacrifice and loss, compromised autonomy and early death,” and this unmistakable assertion from an essay in The Springfield Republican on January 25, 1845: “Marriage is to woman at once the happiest and the saddest event of her life; it is the promise of future bliss raised on the death of all present enjoyment.” She argues that Dickinson avoids the “pathos” of these representations and “ironizes the limited gender roles assigned to women in her culture” in poems like “He put the Belt around my life,” in which “marriage is a kind of colonization of the bride.”

Helen Vendler offers folktale’s “Cinderella” as a backdrop for the insignificant girl who is “hidden royalty,” but also hears an echo of the moment of spiritual and artistic vocation experienced by the English Romantic poet William Wordsworth (1770-1850) in the speaker’s self-description as “a Dedicated sort”:

I made no vows, but vows

Were then made for me; bond unknown to me

Was given, that I should be, else sinning greatly,

A dedicated Spirit.The Prelude (1850) IV, 334-337

Vendler observes:

We meet, in this poem, four Dickinsons: the humble one doing “little Toils” in the routine “Circuit” of the Household; the spiritual “Member of the Cloud” who has business with a celestial Realm; the hidden Duchess who deals out royal smiles; and the poor spinster whom others take pity on, thinking that she needs invitations. Nobody understands her declining of those invitations, because they cannot see the imperial power to whom she belongs.

Formally, Vendler notes, the poem consolidates its four rhymed quatrains into two eight-line stanzas “to demonstrate the two lives that the poet lives.”