On Choosing the Poems and Letter

As we said in the Overview, Dickinson’s fifth letter to Higginson touches on important themes and offers insights into the questions Higginson posed to Dickinson and the commentary he made on her work and her life in his letters, which are lost. We will examine these issues and how the letter fits into the development of their correspondence and relationship in the discussion of the letter below.

For poems this week, we explore the two Dickinson included with the letter, “I cannot dance upon my toes” (F381A, J326) and “Before I got my Eye put out” (F336A, J327), both of which have garnered quite a bit of critical attention. Dickinson introduces them with the plaintive question in the first line of the letter: “Are these more orderly? I thank you for the Truth –,” referring, presumably, to Higginson’s earlier critique that her poetry was disorderly or “Wayward,” as she says in the third paragraph of this letter. We will consider this question as we look at these poems. The first poem touches on performance and is a revealing choice to include in a letter that scholar Jason Hoppe calls “flamboyant.” The second treats blindness, literal and figurative.

In addition, we have chosen poems that explore both of these themes as Dickinson developed them in and around 1862, as well as one poem that depicts a visit from a beloved man. Though it is dated to early 1862 and, thus, must refer to another of Dickinson’s “Master” figures, in many ways the scenario it describes prefigures the visit Higginson finally makes to Dickinson in 1870, suggesting how well she fit him into the pattern of significant males in her life and work.

Dickinson to Higginson, Letter 271

August 1862

Dear friend -

Are these more orderly? I thank you for the Truth -

I had no Monarch in my life, and cannot rule myself, and when I try to organize – my little Force explodes – and leaves me bare and charred -

I think you called me "Wayward." Will you help me improve?

I supposed the pride that stops the Breath, in the Core of Woods, is not of Ourself -

You say I confess the little mistake, and omit the large – Because I can see Orthography – but the Ignorance out of sight – is my Preceptor's charge -

Of “shunning Men and Women” – they talk of Hallowed things, aloud – and embarrass my Dog – He and I dont object to them, if they'll exist their side. I think Carl[o] would please you – He is dumb, and brave – I think you would like the Chestnut Tree, I met in my walk. It hit my notice suddenly – and I thought the Skies were in Blossom -

Then there's a noiseless noise in the Orchard – that I let persons hear – You told me in one letter, you could not come to see me, “now,” and I made no answer, not because I had none, but did not think myself the price that you should come so far -

I do not ask so large a pleasure, lest you might deny me -

You say “Beyond your knowledge.” You would not jest with me, because I believe you – but Preceptor – you cannot mean it? All men say “What” to me, but I thought it a fashion -

When much in the Woods as a little Girl, I was told that the Snake would bite me, that I might pick a poisonous flower, or Goblins kidnap me, but I went along and met no one but Angels, who were far shyer of me, than I could be of them, so I hav'nt that confidence in fraud which many exercise.

I shall observe your precept – though I dont understand it, always.

I marked a line in One Verse – because I met it after I made it – and never consciously touch a paint, mixed by another person-

I do not let go it, because it is mine.

Have you the portrait of Mrs Browning? Persons sent me three – If you had none, will you have mine?

Your Scholar -

DEA transcript: Originally in Boston Public Library (Higg 55). Ink. Courtesy of BPL and Dickinson Electronic Archive. First published in Atlantic Monthly VIII (October 1891), 448-49.

In his reading of the Dickinson-Higginson correspondence, Jason Hoppe calls this fifth letter “exceptionally flamboyant,” and notes that it goes unanswered—Higginson was occupied with training new recruits and in November 1862 would take up command of a regiment of formerly enslaved men in South Carolina. This is the second letter in which Dickinson addresses Higginson as “Dear friend,” (the first time was in the third letter on 7 June), which suggests an equality. But as in the fourth letter, she signs herself “Your scholar,” which suggests her submission to his “Preceptorship.” In the context of the letter, this closing seems gently mocking. A pattern emerges where Dickinson cites one of Higginson’s comments or critiques and then answers it, often obliquely. As Hoppe points out, this is one way Dickinson echoes and inhabits Higginson’s words, but she also, then, turns them to her own purposes and makes them seem irrelevant. She never asks him about himself until the very last paragraph of the letter and, as we will see, that question contains a subtle reminder.

From her opening question: “Are these more orderly? I thank you for the Truth –,” we can infer Higginson’s observation that he found the previous poems she sent him “disorderly.” Dickinson thanks him for his “Truth” and wants at least to appear to take his critique to heart. Her explanation in the next paragraph feels heartfelt, blaming this fault on the lack of a “Monarch” in her life, presumably an authority to govern what she describes as “my little Force,” which is, nevertheless, explosive. In the next moment, though, her tone is coy:

I think you called me “Wayward.” Will you help me improve?

In the next paragraph, a reference to “pride … not of Ourself” seems to absolve her of waywardness, attributing it to an outside force. A poem dated to 1863, “Sweet mountains – ye tell me no ” (F745, J722) provides a fascinating gloss on waywardness.

Higginson appears to have noted this dynamic in Dickinson’s letters, because she parrots him: “You say I confess the little mistakes, and omit the large–.” Nevertheless, she continues. Apparently, he accused her of “shunning Men and Women,” which she answers by saying “they talk of Hallowed things aloud– and embarrass my Dog.” Carlo is an important companion, “dumb and brave,” and a signal element in the scenario of a face-to-face visit, which Dickinson mentions in the next paragraph, and which she outlines in the poem, “Again his voice is at the door” (F274A, J663), discussed below. Next, she quotes Higginson’s demurral that she is “Beyond your knowledge,” but confirms her confidence in him with a remarkable parable about the stories she was told when she was a girl, presumably by her parents, those feckless monarchs in her life, about walking in the woods alone and meeting biting snakes, poisonous flowers, and abducting Goblins. Finding none but shy Angels on her rambles, she learned not to believe in “fraud,” and so insists on taking him at face value—which, of course, he cannot do with her.

What “precept” of his she promises to obey, though not understanding it, is not revealed. Then comes a statement scholars puzzle over about Dickinson’s fear of appearing imitative: seeing one of her ideas, images, or turns of phrase in another poet’s verse and striking it. But the following statement: “I do not let go it, because it is mine,” confuses that reading. With imitation in her mind, Dickinson asks Higginson the only question about himself in the letter, wondering if he has a portrait of Barrett Browning. Could this be an oblique reminder of the female poetic company in which she wishes him to consider her?

Sources

Hoppe, Jason. “Personality and Poetic Election in the Preceptual Relationship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, 1862-1886.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 55, 3 (Fall 2013): 348-387, 360.

I cannot dance upon my toes (F381A, J326)

I cannot dance opon

my Toes –

No Man instructed me –

But oftentimes, among

my mind

A Glee possesseth me

That had I Ballet –

knowledge –

Would put itself abroad

In Pirouette to blanch

a Troupe –

Or lay a Prima – mad –

And though I had no

Gown of Gauze –

No Ringlet, to my Hair –

Nor hopped to Audiences -

like Birds –

One Claw opon the Air –

Nor tossed my shape

in Eider Balls –

Nor rolled on Wheels

of Snow

Till I was out of

sight in sound –

The House encore me

so –

Nor any know I know

the Art

I mention easy – Here –

Nor any Placard boast

me

It's full as Opera –

EDA manuscript: Originally in Houghton Library MS Am 1118.1 (15). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Further Poems (1929), 8, from the fascicle copy (B), without stanza division, in twenty-one lines.

In Fall 1862, Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 19 in the third position. While it’s not clear what for Dickinson constituted the “more orderly” poetry Higginson asked of her, this poem has a mostly regular syllabic structure of 8686 and an almost discernible rhyme scheme. It's the poem’s unmistakable mood of confidence, and its bold declaration of artistic independence—“No Man instructed me”—that might have struck Higginson as somewhat “unruly” or at least ironic in terms of the framing letter’s many protestations of Dickinson’s submission and obedience to his “precepts” about poetry. In the poem's fantasy of having “Ballet knowledge” and putting it “abroad” to great acclaim, is Dickinson mocking Higginson’s injunction that she not publish?

Scholars who discuss this poem talk about its emphasis on performance, technique, and the use of dance as a metaphor for writing, also noting its tone of comedy and parody. The “Gown of Gauze,” the “Ringlet” in the hair, hopping like birds, which might be an allusion to the ballet Swan Lake, with its costumes shaped like “Eider [goose feather] Balls,” or The Nutcracker with its large sleds on “wheels of snow,” all deflate the seriousness of this classical art form and suggest an impatience with the “conventional” form Higginson was pressing on Dickinson and which he and Mabel Todd successfully imposed on her poetry they edited and published after her death.

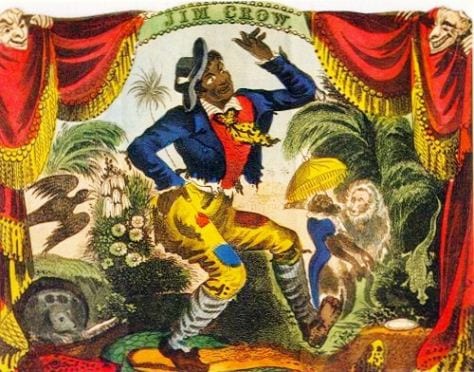

In a notable reading, Sandra Runzo frames this poem in terms of Dickinson’s knowledge of popular music and popular culture, specifically of blackface minstrelsy. She notes that a common name for minstrel songs was “Ethiopian Glee,” and minstrel shows were known as “Ethiopian Opera,” two words that appear in the poem. Other terms associated with minstrelsy are “troupe,” “blanch” and “prima.” Apparently, the female impersonator of the minstrel show was called the “prima donna,” who by 1860 had a well-established role in minstrel performances. This impersonation is central to the poem’s satire. Another hint is the description of the dancer hopping, “One Claw opon the air–,” a gesture that mimics the poses of minstrel dancers and “even the famous ‘Jim Crow.’”

By alluding to the minstrel show, according to Runzo, Dickinson taps into a cultural conversation

that addressed vital questions of personal and public identity and that debated the social struggles of her day.

Furthermore, she says, the mixing of allusions to high culture and low culture

carries an implicit class consciousness, suggesting the speaker’s own divided or mischievous sensibility; she courts the classical arts but identifies with the popular forms. In addition, notions of gender are wheeled around, the regalia and postures of the prima ballerina parodied and replaced with the playful (or earnest) performance of the prima female impersonator.

Sources

Runzo, Sandra. “Popular Culture.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Ed. Eliza Richards. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, 216-25.

For an unorthodox reading of this poem, see Jerome Charyn. “Ballerinas in a Box.” A Loaded Gun: Emily Dickinson for the 21st Century. New York: Bellevue Literary Press, 2016.

Before I got my Eye put out (F336A, J327)

Before I got my eye

put out

I liked as well to see –

As other Creatures, that

have Eyes

And know no other way –

But were it told to

me – today –

That I might have the

sky

For mine – I tell you

that my Heart

Would split, for size of

me –

The meadows – mine –

The Mountains – mine –

All Forests – Stintless Stars –

As much of Noon

as I could take

Between my finite eyes –

The Motions of The

Dipping Birds –

The Morning's Amber

Road –

For mine – to look

at when I liked –

The News would strike

me dead –

So safer Guess –

With just my soul

opon the Window pane –

Where other Creatures

put their eyes –

Incautious – of the Sun –

EDA manuscript: Originally in Houghton Library A.MS. (unsigned) poem; 1s. (3p.) MS Am 1118.1 (14). Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Poems (1891), 60-61, as five quatrains, from the fascicle copy (B), with the alternative not adopted.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 16 in the first place, a position that often suggests the announcement of a theme. The startling first line certainly catches our attention. It is also quite regular in terms of the 8686 syllabic pattern, but completely “slant” in terms of rhyme.

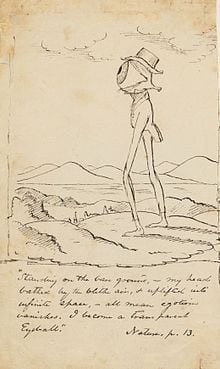

Several scholars read this poem in terms of the eye problems Dickinson began suffering that in 1864-65 sent her to Cambridge to be treated by an eye specialist, who forbade her to read or write for a long period of time. It’s important to note, however, that the speaker talks about having her eye, singular, “put out,” as if by way of punishment or deliberate disfigurement. She might have been thinking about Gloucester in King Lear, or other characters who go blind like Romney in Barrett Browning’s Aurora Leigh or Rochester in Jane Eyre. This singular “eye” might also allude to the “I” of the Transcendental poet, especially to Emerson’s famous and parodied description in his essay Nature (1836) of his moment of epiphany walking across the Cambridge Commons in which he becomes a “transparent eyeball.”

This poem also suggests that there are different kinds of seeing, which the speaker only learns about after experiencing blindness. There is a physical form of seeing, “As other Creatures, that have Eyes / And know no other way,” and an imaginative, inner form of seeing with the soul, which allows the speaker to possess, rather than just see, the daily natural beauty of this world. That the “News” of this kind of seeing “would strike [the speaker] dead” suggests it has a spiritual component, since the Gospel message of Christian salvation and immortality is called “the good news.”

Is there a message in this poem for Higginson about appearances, about his ability to really see Dickinson?

Again – his voice is at the door – (F274A, J663)

Again – his voice is at

the door –

I feel the old Degree –

I hear him ask the

servant

For such an one – as me –

I take a

flower – as I go –

My face to justify –

He never saw me – in

this life –

I might surprise [not please] his

eye!

I cross the Hall

with mingled steps –

I -silent [speechless] – pass the

door –

I look on all this

world contains –

Just his face – nothing

more!

We talk in

careless [venture]- and in toss –

A kind of plummet

strain –

Each – sounding – shily –

Just – how – deep –

The other's one – had been [foot had been]-

We walk – I

leave my Dog – at home [behind] –

A tender – thoughtful

Moon

Goes with us – just

a little way –

And – then – we are

alone –

Alone – if Angels

are "alone" –

First time they try the

sky!

Alone – if those "vailed faces" – be –

We cannot count – [that murmur so- / that Chant so, far]

On High!

I'd give – to live that

hour – again –

The purple – in my

Vein –

But He must [should] count

the drops – himself -

My price for every

stain!

EDA manuscript: Originally in Amherst Manuscript #set 89- Of nature I shall have enough – asc:7239 – p. 8. Courtesy of Amherst College, Amherst, MA. First published in Bingham, Ancestors’ Brocades (1945), 273, the second stanza; Bolts of Melody (1945), 142-43, entire, as seven quatrains, with the alternatives for lines 13, 17, and 18 adopted.

Dickinson’s concern, even obsession with face-to-face meetings and with what faces reveal is captured in this poem, written in early 1862 on embossed notepaper, as if it might have been intended for inclusion in a letter. The variants are written in above and below the words in the poem and so we put them into square brackets. The poem also has an unusual amount of underlining, which we rendered in italics.

Although the poem could not have been written about a real or even imagined meeting with Higginson, it prefigures some of the elements of their first meeting, which took place in 1870, and which Higginson described in great detail in a letter to his wife (L342). His account included Dickinson giving Higginson two day lilies by way of introduction, but not a walk outside with or without Carlo.

Dickinson reprises other phrases in this poem about the meeting of lovers in her fifth letter to Higginson, discussed above. She suggests that in an earlier letter Higginson broached the possibility of coming to Amherst to see her, because she refers to his comment that he

could not come to see me, “now,” and I made no answer, not because I had none, but did not think myself the price that you should come so far – / I do not ask so large a pleasure, let you might deny me–

The word “price” also appears in the last line of the poem, alluding to a sacrifice of blood (“purple– in my Vein”) that the meeting or the separation cost these lovers. In her letter Dickinson uses “price” to describe “herself” as the object of Higginson’s efforts. Both uses suggests the monetizing of desire in Dickinson’s writing we explored last week in the post on Wealth, Class, and Economics. The parable Dickinson relates in her letter also contains the “shy Angels” in the woods the lovers meet in this poem as they walk abroad. This poem also echoes “There came a day– at Summer’s full” (F325B, J322), a great poem of renunciation. All of this suggests that Dickinson was using language to weave Higginson into the an archetypal scenario of climactic visit.

From blank to blank (F484A, J761)

From Blank to Blank –

A Threadless Way

I pushed Mechanic feet –

To stop – or perish -

or advance –

Alike indifferent –

If end I +gained

It ends beyond

Indefinite disclosed –

I shut my eyes – and

groped as well

'Twas +lighter – to be Blind –

+ reached + firmer

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XXXI, Fascicle 23, Houghton Library – (166c). Includes 20 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Further Poems (1929), 182, as two six-line stanzas, with the alternatives not adopted.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 23 in the 6th place in late 1862. We include it here as another perspective on blindness written at about the same time as the fifth letter to Higginson. The first stanza echoes the lines and dark mood of “After great pain, a formal feelings comes” (F372A, J341) where “The Feet, mechanical, go round – A Wooden way,” and the meaningless movement “From Blank to Blank” echoes “Like Eyes that looked on Wastes – / Incredulous of Ought / But Blank – and steady Wilderness …” (F693A, J458.)

Cynthia Wolff includes this poem in a group she calls the “the poetry of existential pain” and explains:

“Blank” is almost a totemic word in Dickinson’s work to identify a course of human affairs that has been stripped of larger significance. Now the “thread” of meaningful narrative sequence is gone, and there are no defined beginnings or endings to be acknowledged or rejected. Even the structure that the drive toward death had imposed has been lost, and poetry bears a commensurate wound … What now can dictate the shape of art?

What Wolff does not note is how this imagery suggests the sewing and binding of the booklets of fair copies of poems Mabel Todd called “fascicles,” which occupied Dickinson during this period. Even this poetic labor seems pointless.

What does the speaker shut her eyes against? In the indifference of existential pain, literal blindness seems paradoxically “lighter/firmer” than human sight, which only “discloses” the “indefinite.”

Source

Wolff, Cynthia. Emily Dickinson. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc. 1988, 472-73.

An ignorance a sunset (F669A, J552).

An +ignorance a Sunset

Confer opon the Eye –

Of Territory – Color –

Circumference – +Decay –

It's Amber Revelation

Exhilirate – Debase –

Omnipotence' + inspection

Of Our inferior face –

And when the solemn

features

+Confirm – in Victory –

We start – as if

detected

In Immortality –

EDA manuscript: Originally in Poems: Packet XVII, Mixed Fasciles, Houghton Library – (96a). Includes 25 poems, written in ink, ca. 1862. Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge, Mass. First published in Unpublished Poems (1935), 50, with the alternatives not adopted.

Dickinson copied this poem into Fascicle 30 in the 18th place. While Franklin dates it to the second half of 1863, Johnson dates it to 1862. It expands on the motif of seeing faces we have explored in these poems from the suggestion in Dickinson’s fifth letter to Higginson, with the added attraction of a reference to “Circumference,” one of the most potent terms in Dickinson’s lexicon.

At the outset of the poem, a sunset confers “An ignorance … upon the Eye.” The variant “impotence” makes this statement even stronger. It might mean that an ordinary viewing of this daily image of glory, one that encompasses “Territory,” “Color,” and “Circumference,” does not expand or enlighten the physical eye/I but rather “decays” it. The speaker suggests that our viewing of a sunset is like a face-to-face meeting with the “Omnipotence” of a divine force, and in this meeting our face proves “inferior.” What comes to mind is Moses on Mount Sinai asking to see God's glory, to which God replies:

"I will make all My goodness pass before thee; and I will proclaim the name of the Lord before thee, and will be gracious to whom I will be gracious, and will show mercy on whom I will show mercy."

And He said, “Thou canst not see My face, for there shall no man see Me and live.” (Exodus 33:18-20)

Moses is granted a partial “theophany,” the visible presence of God, and it signals some new beginning. Moses came down from Sinai with a shining face and the tablets of the Ten Commandments. In Dickinson's poem, when the superior face of this force, the sunset, withdraws or confirms its “Victory” over us, we “start,” a verb that has multiple meanings of “spring to attention,” “become active,” “startle,” also “begin a trip or journey,” as if we have been discovered in a form of incipient “Immortality.” Thus, is human ignorance/sight amended and linked to a deeper apprehension of life’s and death’s mysteries.

Source

Hallen, Cynthia, ed. Emily Dickinson Lexicon. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 2007.

Sources

Hoppe, Jason. “Personality and Poetic Election in the Preceptual Relationship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson, 1862-1886.” Texas Studies in Literature and Language 55, 3 (Fall 2013): 348-387, 360.