Mural Art in Mexico & U.S.

Professor Moody

20 January 2017

Mestizaje

A strong sense of pride resounds within the Mexican culture. For many, Mexico was the only place they had ever known. Each person was bound to the other in their roots—they lived in a place incredibly rich in history. When the Spanish conquistadors attempted to change the indigenous inhabitants’ way of life in the early 20th century, the original people of Mexico bound themselves in opposition to these European people. For many years, the indigenous people of Mexico were in a constant battle with these new white faces. They fought against the subjugation of these tyrants believing that one race, even if it was a mixed race, would not be the answer to their underlying problems with the European culture.

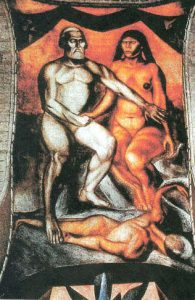

The feelings and beliefs of many Mexican people can vividly be seen in the work of artist José Clemente Orozco, particularly in his fresco Cortez and Malinche (See Figure One). In this work, Orozco depicts a very white Cortez sitting next to an indigenous woman, Malinche. This image symbolizes the creation of the very first mestizo—the very first child born with both a white and an indigenous parent. Cortez and Malinche therefore are considered to be the parents of what is known as the Mexican race today (Garsd).

In this image that Orozco painted, they are both naked and completely vulnerable. They are holding hands symbolizing a union, yet Cortez has his left arm held across Malinche’s chest as if to show power. This is symbolic as Malinche and the unknown man at the bottom of the page have the same skin color, and he is separating her from the man lying prone on the bottom of the image. Cortez’s eyes are looking ahead to the right, as if to be looking into the future—the future of Mexico. “The Cortez and Malinche fresco was the first direct reference by the Mexican muralists to one of the most significant results of Spanish colonialism in Mexico, that of the miscegenation or Mestizaje of the indigenous population” (Rochfort 44). The future that Mexico would know after this point would be an extremely tumultuous one, full of war and changes in political power.

Porfirio Diaz was the self-proclaimed president of Mexico for decades, until the people of Mexico wanted a change. Diaz was a dictator, and the people wanted someone who would govern them in way that would represent their best interests. Hearing this, Diaz fled the country and a new leader, Madero, stepped into power in 1911. However, his rule did not last long as he was soon assassinated and replaced by Huerta in 1913. Huerta very soon is threatened by many outside forces, including the United States, and flees the country in 1914. Carranza, who played a major role in eliminating Huerta from power, is then recognized as President of Mexico. In 1920, Carranza was murdered and replaced as President of Mexico by Obrégon. Once Obrégon was sworn into the Presidency, the Mexican Revolution was officially over (Library of Congress).

The Azuela novel, The Underdogs, does a great job of displaying the Mexican Revolution from a soldier’s point of view. At one point in the novel, in the heat of battle, Solís, a middle class soldier, cries out:

Such a shame that what must come now shall not be quite as beautiful. We must wait a bit. Until there are no more combatants, until no shots are heard other than those of the masses surrendered to the delight of plundering. Until the psychology of our race can shine diaphanous, light as a drop of water, condensed into two words: theft, murder! What a disappointment it would be, my friend, if those of us who came with all our enthusiasm, with our very lives, to defeat a wretched assassin, turn out to be the builders of an enormous pedestal upon which a hundred or two hundred thousand monsters of the same species might arise! A nation without ideals, a nation of tyrants! The shame of blood! (Azuela 68).

His feelings towards the destruction that was happening around him reflected that of many other Mexican soldiers. They were all sick of having multiple dictators trying to take over Mexico. They wanted someone who would step into power and rule on behalf of the citizens of Mexico. When Obrégon stepped in, that is what happened. However, the Mexican people were fresh from a very serious and destructive decade of hate and violence. They were torn because of race and the power of the class system. The Mexican people had a hard time coming together because of this, and uniting was something incredibly necessary for them to have a prosperous future.

Mural art was something the Mexican government wished to expand on in order to help heal the wounds still fresh from the war. In 1923, shortly following the Mexican Revolution, philosopher and politician José Vasconcelos commissioned Orozco to paint the Cortez and Malinche (Figure One) fresco explained above. Although it is depicted in the colonial period, looking back on it so soon after the war was meant to be healing. Orozco’s image shows the birthplace of the entire country of Mexico. Cortez and Malinche are seen as parents of almost everyone in Mexico. Because of this, every single person is connected. Looking at this image, the people of Mexico can recognize they all came from the same place, they all went through war and destruction together as a people, and they are in a new place now. Even though it was a very messy past, all the people of Mexico are united in it. The Mexican people can look back on their past as one people and be reminded that their future does not need to reflect it.

Works Cited

Azuela, Mariano. The Underdogs, a Novel of the Mexican Revolution. New York: New

American Library, 1963. Print.

Garsd, Jasmine. "Despite Similarities, Pocahontas Gets Love, Malinche Gets Hate. Why?" NPR.

NPR, 25 Nov. 2015. Web. 26 Jan. 2017.

"The Mexican Revolution and the United States in the Collections of the Library of

CongressTimeline." Timeline - The Mexican Revolution and the United States |

Exhibitions - Library of Congress. Library of Congress, n.d. Web. 26 Jan. 2017.

Rochfort, Desmond. Mexican Muralists: Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros. San Francisco: Chronicle,

- Print.