Response Paper 3: Who Authorizes and Supports the Production of Public Art?

Declan McGonagle accurately describes both the essence and impact of public art in his article, Public Art when he writes, “Even when such work is pretending simply to provide formal solutions to formal problems, like all culture, it still reflects and embodies the momentum of society” (McGonagle 42). Public art has not always been so prominent in today’s community, for it truly did not become a popular movement until the 1980s (Zebracki 303). Because they were painting public murals in Mexico in the 1920s, this is what makes men such as José Clemente Orozco, Diego Rivera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros artistic revolutionaries, as they paved the way for an increasing amount of public art in the future through their creations of murals that reflected scenes of the Mexican Revolution, communist policies, and the mestizo. When thinking about public art, it is important to consider who authorizes and supports its production, for the majority of public art is not created without some form of controversial content. The works of Suzanne Lacy, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Frida Kahlo are notable contributors to the public art movement mostly for their portrayal of feminist themes in correspondence to the context of the feminist movement. Kahlo and O’Keeffe’s works are considered public art in a different manner, for their work consisted most of easel and water color paintings, which were originally exhibited in galleries and were held in private collections, but in recent years have been displayed through numerous advertisement and forms of merchandise. The feminist, outspoken, and contentious content of Kahlo, O’Keeffe, and Lacy’s work, as well as their ability to spark reaction from various audiences is what allowed their pieces to be so heavily supported by the general public or authorized in various museums. Despite the fact that all three of these women are unified by their feminist values and relevant, artistic themes, there is a clear distinction between being a public artist, and producing public art.

In her essay A Small World That’s Become So Big…, Ingried Brugger pins the essence behind Kahlo’s artistic content when she writes, “She reacted to her immediate environment, sometimes allowing herself political allusions or, more precisely, portrayals of the connections she perceived between her own person and wider complexes of ideas” (Brugger 12). During the time she was creating paintings, Kahlo’s work was not popular or frequently supported. Kahlo received few authorized exhibitions, and received most of her fame from being married to Diego Rivera, who was a very successful at the time in Mexico, Europe, and the United States (Brugger 12). However, in the present time, Kahlo is one of the most recognized female artists in the creative world. Her painting, Henry Ford Hospital (1932) is one of her most famous easel paintings, which depict Kahlo’s post-miscarriage depression. Originally called The Lost Desire, Kahlo includes six symbols (a medical model, the dead child, a snail, a machine, a flower, and a pelvis) to thoroughly portray her struggle after the death of her child, as well as create seriously sexual and satirical undertones. For example, the snail is supposed to resemble the moon in the painting, but Kahlo expands this a step further as she conveys the snail to be sliding in and out of its shell, creating a sexual metaphor (Prignitz-Poda 102). Although Kahlo’s work was not displayed in generally public vicinities, and access to her paintings was limited to museums and galleries with an audience narrowed to artists, Kahlo’s tendency to create art contrary to social norms is what inadvertently gave her a feminist label as time went on. Kahlo’s transition from a struggling artist to a symbol of social progressiveness clarifies that although her art was by no means performance or public art, her name recognition, as well as the reproduction and merchandising or her work, categorizes her immensely universal painter.

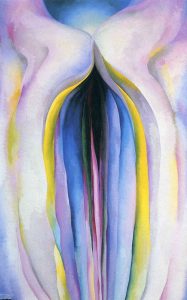

Similar to Kahlo, Georgia O’Keeffe is another prominent artist of the 20th century, who inadvertently created feminist art as well becoming a public figure. Despite the fact that O’Keeffe was a member of the National Women’s Party in the 1910’s, she publicly denounced any claim that her art was meant to be feminist as well as stating her lack of support for any feminist art projects (Ellis—Peterson 1). Although her membership to a feminist group and denial to any sort of “feminist” label is contradictory, her art does in fact reflect feminist themes whether she intended to or not. The paintings that O’Keeffe is most recognized for are her flower series, in which she carefully constructs replications of various blossoms as if they were being looked at through a magnifying glass. The first showing of the flower series was at the 219 Gallery in New York in the 1920s, and since then, O’Keeffe has been a lasting presence in the art world. Similar to Kahlo, much of O’Keeffe’s popularity culminated from her impressively famous, photographer husband, Alfred Stieglitz, who was the first to authorize her work in 1919. O’Keeffe’s marriage to Stieglitz is similar to the marriage between Kahlo and Rivera, since both women were married to men, and famous artists, who facilitated in bringing their artwork to a larger audience in a world that still viewed women as socially inferior. Nowadays, much of O’Keeffe’s work can be found in the Tate Modern, located in London, England, which showcases international modern and contemporary art. Achim Borchart Hume, who is the museum’s director of exhibitions, stated the reasoning behind the showcasing O’Keeffe’s work to be “Many of the white male artists across the 20th century have the privilege of being read on multiple levels, while others—be they women or artists from other parts of the world—tend to be reduced to one conservative reading. It’s high time that galleries and museums challenge this” (Ellis—Petersen 1). Hume makes a valid point in arguing that in order for women, or other artists that are not white males, to truly gain professional prestige in the artistic world, their work needs to be both prominent and show cased for long periods of time in museums and collections.

O’Keeffe’s Grey Lines With Black, Blue, and Yellow is an example of one of her many flower paintings that received a great amount of success during her career. The piece is slightly abstract since it is difficult to tell whether O’Keeffe is attempting to portray a form of plant life or female genitalia. This debate over what O’Keeffe is actually trying to convey is extended by the intentional use of three-dimensional lines that shape what is to be viewed as either a flower or a vagina. The colors within the painting, blues, greys, purples, black, and yellows are contrasting yet both euphoric and lustful. If O’Keeffe were alive to explain her symbolic intentions, she most definitely would claim that the piece has no sexual implications, but instead represents natural elements of the world she lived in (Ellis—Petersen 1). Furthermore, it is important to note that her husband, Alfred Stieglitz, introduced the interpretation of O’Keeffe’s work to resemble the female anatomy when he was beginning to publicize her art. However, since Stieglitz was the mind behind the symbolism of O’Keeffe’s flowers, and the fact that O’Keeffe refused to identify with any feminist labels, this acts as substantial evidence that O’Keeffe may simply have been just painting images of nature. Nonetheless, this does not diminish from the idea that her work represents feminist values since her accomplishments as a female artist in the 20th century were monumental. Her piece, Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1, was sold for $44.4 million dollars three years ago, making the painting the most costly work of art sold that was created by a female artist (Ellis-Petersen 1). O’Keeffe is quoted, “Men put me down as the best woman painted…I think I’m one of the best painters”, which attributes to her lack of conformity and confidence that inspired many eager, working females (The Tate Modern 1). Like Kahlo, O’Keeffe’s independent behavior and artistic content sparked the transition of her paintings being showcased in galleries and museums, to being nationally distributed, as well as creating her brand name and becoming a prominent artistic figure.

Contrasting from both Kahlo and O’Keeffe, Suzanne Lacy was neither commissioned by galleries nor museums, but instead impacted audiences on a local level by showcasing her art in largely public facilities (Fryd 23). Lacy’s most recognized example of public art is found in her exhibition, Three Weeks In May. Lacy’s intention behind the three week long display was to expose the frequency of rape, abuse, and sexual assault of women in Los Angeles. According to Vivien Green Fryd in her analysis of Three Weeks In May, Lacy “marked the establishment of New Genre Public Art, a socially engaged, interactive cultural practice that deploys a range of traditional and nontraditional media in public spaces for public audiences, intersecting activism, education, and theory” (Fryd 23). The difference between Lacy from Kahlo and O’Keeffe is that Lacy’s feminism was intentional. Furthermore, it did not take Lacy years for her artwork to gain recognition, unlike Kahlo and O’Keeffe, since her work consisted strictly of public art and was already available to so many people. Taking place in The City Mall Shopping Center, Lacy was strategic in her choice of setting because the location was near the Los Angeles City Hall. The notion to place the art in a public mall was to enlarge and diversify the audience Lacy hoped to connect with, primarily being women. Her dedication to feminism as well as political activism drove Lacy to want to attack, as well as assemble, governmental power and protest gender patterns.

The three images above represent the content in which Lacy included in her exhibition, Three Weeks In May. The first image showcases the street art that Lacy created to emphasize the reality of rape and how close it can be citizens in any community. The second image was showcased inside the City Mall Shopping Center and consists of a map and all of the areas in which women were raped spray painted in red. Lacy added to the spray painted labels as she checked the police reports daily for more cases of sexual assault against women (Fryd 23). The final picture exposes on the ignorance of society in the blindfolding of the female model, emphasizing Lacy’s political activism as one of her goals of Three Weeks In May was to spark a reaction from local institutions. Lacy’s work is highly applauded as she worked to raise awareness about many areas in society such as education and the suppression of minorities. Had it not been for her provocative, relevant content, as well as the being in the context of the women’s rights movement and other social movements, Lacy’s work would not have been as highly acclaimed.

In conclusion, the fact that Kahlo, O’Keeffe, and Lacy’s work was so controversial and outspoken against gender norms allowed their artwork to be featured in numerous galleries, museums, and public venues. While Kahlo and O’Keeffe did not intentionally include feminist themes in their work, the artwork of all three women is bound by the common notion of challenging gender norms and furthering women’s rights. It is important to consider who authorizes public art, as well as who supports it, but it is also important to understand the difference between public artists versus public art. While public art is not necessarily limited to art on or inside public buildings, its genre is very specific. Kahlo and O’Keeffe did not create forms of public art, but are widely known artists because of their original content and vast reproduction of their work around the world. The purpose of every form of art is to influence an audience, and while Kahlo, O’Keeffe, and Lacy’s genres differ, they are united by this artistic goal. Who authorizes art, who supports art, and society as a whole will change as time goes on, the goal of any artist will remain the same—to impact their viewers—no matter in what setting or form it exists.

Works Cited

Ellis-Petersen, Hannah. “Flowers or Vaginas? Georgia O’Keeffe Tate Show to Challenge Sexual Cliches.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 01 Mar. 2016. Web. 03 Mar. 2017.

Fryd, Vivien Green. “Suzanne Lacy’s Three Weeks in May: Feminist Activist Performance Art as “Expanded Public Pedagogy”.” NWSA Journal 19.1 (2007): 23-38. Web. 2 Mar. 2017.

McGonagle, Declan. “Public Art.” Circa Art Magazine 50 (1990): 42-43. Web.

Prignitz-Poda, Helga, and Ingried Brugger. Frida Kahlo Retrospective. Berlin: Prestel, 2010. Print.

Tate. “Georgia O’Keeffe – Exhibition at Tate Modern.” Tate. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2017.

Zebracki, Martin. “Beyond Public Artopia : Public Art as Perceived by Its Publics.” GeoJournal 78.2 (2013): 303-17. Web. 2 Mar. 2017.