From Feminists to Public Figures: Frida Kahlo, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Suzanne Lacy

“Feminist: a person who believes in the social, economic, and political equality of the sexes”, these are the words of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, a globally recognized author known for her writing discussing both racism and feminism (Bury 1). While the concept of feminism is simple, the overall formation of the movement has been slow. Nonetheless, as women began to stand up for their rights, women began to create art in reaction to the brave, confident, and gender proud themes being displayed by other feminists. Like the public art movement, the feminist art movement did not truly begin until female artists began to creatively reflect their experiences as being seen as socially inferior based on their gender. Artistic movements in general must contain provocative, nontraditional content in order to inspire reaction from an audience. Because they were painting such controversial content in Mexico in the 1920s, this is how men such as José Clemente Orozco, Diego Riviera, and David Alfaro Siqueiros became artistic revolutionaries. “Los Tres Grandes”, as they were widely known, paved the way for an increasing amount of public art in the future through their creations of murals that reflected scenes of the Mexican Revolution, communist politics, and the mestizo. When thinking about art in general, it is important to consider who authorizes it and supports its production. In the sense of the feminist art movement, those that authorized the works of Suzanne Lacy, Frida Kahlo, and Georgia O’Keeffe are incredibly significant to take in to account, since purchasers were supporting both a woman and extremely contentious material. While Lacy is considered one of the most famous female public artists of all time, Kahlo and O’Keeffe’s works are considered public art in a different manner, for their work consisted mostly of easel and water color paintings, which were originally exhibited in galleries and were held in private collections. However, in recent years, Kahlo and O’Keeffe’s paintings have been displayed through numerous advertisement and forms of merchandise. The feminist, outspoken, and contentious content of Kahlo, O’Keeffe, and Lacy’s work, as well as their ability to inspire reactions from various audiences is what allowed their paintings to be so heavily supported by the general public and authorized in various museums. Despite the fact that all three of these women are unified by their feminist values, there is a clear distinction between being a public artist, and producing public art.

Before the paintings of Kahlo, Lacy, and O’Keefe are discussed, it is important to understand what characterizes feminist art from other forms of work. To be short, the genre itself is significantly broad, for a lot can be considered feminist art in the sense of understanding the intention of the artist. However, more often than not, feminist art can be identified by, “aesthetic features, such as color, shape, balance, and imitation of people and objects found in the real world, but it can also be appreciated for its nonaesthetic features, such as content and contextual meaning within the broader society” (Brand 168). To expand on this idea, feminist art has commonly been a form of political art, for much of the artwork has been a direct reaction stemmed from the misogynistic portrayals of women by men. Art critic, Lucy R. Lippard extended the thought of feminist art as political art when she called the genre a form of “propaganda” (Brand 168). Feminist art as a form of propaganda makes sense due to the fact that first, the artwork is advocating for a specific cause, and two, one of the intentions of the artist is to spread the feminist word as well as earn an impactful amount of supporters to further the meaning behind the work. An example of such can be found by the public art works of Suzanne Lacy, which exposes feminist ideals in parks, plazas, and other public areas easily accessible to a large number of citizens. However, one of the most favorable characteristics of feminist art is that the intention behind the work can be effortless. For example, during Frida Kahlo’s time, feminism was not a prominent subject; however, Kahlo’s defiance, confidence, and consistency in her own character set the precedent for her artwork to be interpreted as feminist art in years to come. Much of Kahlo’s artwork is characterized by her own personal experiences, which affected who authorized her art, and who supported it.

In her essay “A Small World That’s Becomes So Big…,” Ingried Brugger pins the essence behind Kahlo’s artistic content when she writes, “She reacted to her immediate environment, sometimes allowing herself political allusions or, more precisely, portrayals of the connections she perceived between her own person and wider complexes of ideas” (Brugger 12). Brugger’s words effectively convey Kahlo’s artist trends in content, presenting evidence as to why her work was so controversial, revolutionary, and contextual. During the time she was creating paintings, Kahlo’s work was not popular or frequently supported. Kahlo received few authorized exhibitions, and received most of her fame from being married to Diego Rivera, who was very successful at the time in Mexico, Europe, and the United States (Brugger 12). During Kahlo’s lifetime, the feminist movement was not prominent, and traditional values favoring men still dominated society. However, in the present time, Kahlo is one of the most recognized female artists in the creative world. Kahlo was not a self-proclaimed feminist, but demonstrated through her impulsive, independent attitude all of the characteristics that currently categorize a feminist, believing “in the social, economic, and political equality of the sexes” (Bury 1). Her painting Henry Ford Hospital (1932) is an example of how Kahlo, inadvertently, created feminist art.

Originally called The Lost Desire, Kahlo painted this piece after her miscarriage and it was featured in one of her few exhibitions in New York and Paris. In the painting, Kahlo depicts herself in a hospital bed in Detroit in immense pain, sorrow, and distress. Blood covers the bed, and six objects float around the shape of the hospital bed. The first, most noticeable object is Kahlo’s dead son, who is depicted as calmly floating to heaven. To the right of the deceased fetus is a snail, which Kahlo uses to replace the traditional view of the Virgin Mary’s soul making its way to heaven with the sun and the moon surrounding its descent. The snail is supposed to resemble the moon, but Kahlo expands this a step further as she portrays the snail sliding in and out of its shell, creating a sexual metaphor. To the left of the child fulfills the symbol of the sun within the scene of the Virgin Mary in the shape of a medical exemplary. Kahlo extends her sexual metaphor of “the moon” and snail by symbolizing the Aesculapian model to mirror the craving for a male figure. Beneath the hospital bed, Kahlo paints what she is left with in the world after her son’s death. Towards the bottom right, she depicts a pelvis to resemble the process of carrying a child and the pain in which her body went through during the miscarriage. Furthermore, the orchid in the middle symbolizes her child’s short life on earth through the stem of the flower being cut so terse. Finally, in the bottom left corner, Kahlo portrays a machine, which has received numerous interpretations overtime. However, the analysis that best aligns with Kahlo’s feminist tendencies, as Helga Prignitz-Poda explains represents “With the non-functional machine element, Frida is denoting Rivera’s penis enclosed in a metallic chastity belt. Just as the empty pelvis bone demonstrates her lack of lust on the female side, the metallic condom signifies his sexual abstinence of his side” The red lines attaching all six objects to Frida’s stomach serve as arteries, depicting her physical connection to these different symbols (Prignitz-Poda 102). Henry Ford Hospital’s authorization directly links to the fact that is message depicting the effect of miscarriages on women, and also the acceptance of women not always wanting children was relatable to many female viewers at the time of its creation, and also matched the evolving acceptance of women’s rights in the 1930s. Although Kahlo’s work was not displayed in generally public vicinities, and access to her paintings was limited to museums and galleries with an audience narrowed to artists, Kahlo’s tendency to create art contrary to social norms is what inadvertently gave her a feminist label as time went on.

To further the argument that Kahlo unintentionally created feminist art, her painting A Few Small Nips projects strong feminist themes as it depicts the gruesome effects of domestic abuse on women. The piece portrays a naked woman bleeding out on a bed with one shoe and sock on. Above her stands a fully clothed man, holding a knife, as well as being covered in the woman’s blood. The woman in the painting appears to be Kahlo, and the man is Kahlo’s husband, Diego Rivera. However, in addition to reflecting Diego and herself, Kahlo is depicting a murder that actually occurred in Mexico. “The murderer, the husband of the victim, justified himself before the judge with the ludicrous statement, ‘But they were only a few small nips’” (Prignitz-Poda 108). The motive for the murder was the wife’s adultery, an egregious crime to commit as a woman in a society favorable to men. Kahlo references the husband’s infamous quote during the trial with the placement of, “unos cuanto piquetitos!” (a few small nips), in the actual painting directly above the scene of the murder. The fact that Kahlo is portraying an event that actually occurred is important in understanding her tendency towards having a reactionary response while creating her artwork, meaning that Kahlo tended to paint exactly what she was feeling as events happened in her life. Furthermore, Kahlo uses the murder to relate to her own relationship with Diego Rivera, and she does so by placing herself as the murder victim and Riviera as the murderer. Kahlo hopes to expose the unhealthy marriage she and Diego had by painting themselves, since they both committed numerous forms of adultery. Furthermore, Kahlo creates a metaphor by insinuating the many “nips” or stab wounds to resemble the psychological damage Diego inflicted on her (Prignitz-Poda 108). A Few Small Nips is a form of feminist art due to the fact that it discusses the serious problem of domestic violence; exposing both the physical and psychological effects abuse has on women, as well as displaying the female anatomy. Although Kahlo had no feminist intent while creating A Few Small Nips, this sort of content is what eventually allowed her to become such a well-known artist, as well as a strong representative for the feminist movement. Kahlo’s transition from a struggling artist to a symbol of social progressiveness clarifies that although her art was by no means performance or public art, her name recognition, as well as the reproduction and merchandising or her work, categorizes her as a public artist.

Similar to Kahlo, Georgia O’Keeffe is another prominent artist of the 20th century, who inadvertently created feminist art as well becoming a public figure. Interestingly enough, Kahlo and O’Keeffe were very close friends due to the fact that O’Keeffe spent a good portion of time in Mexico, and Kahlo accompanied Riviera to America when he was working on his murals. On many accounts, Kahlo and O’Keeffe exchanged letters, which revealed delicate insight into their personal lives (Patron of the Arts 1). Despite the fact that O’Keeffe was a member of the National Women’s Party in the 1910’s, she publicly denounced any claim that her art was meant to be feminist as well as stating her lack of support for any feminist art projects (Ellis—Peterson 1). Although her membership to a feminist group and denial to any sort of “feminist” label is contradictory, many artists and audiences interpret O’Keeffe’s work to be feminist because of her tendency to create shapes resembling the female genitalia, as well as the professional prestige she earned as a female. The paintings that O’Keeffe is most recognized for are her flower series, in which she carefully constructs replications of various blossoms as if they were being looked at through a magnifying glass. The first showing of the flower series was at the 219 Gallery in New York in the 1920s, and since then, O’Keeffe has been a lasting presence in the art world. Similar to Kahlo, much of O’Keeffe’s popularity culminated from her impressively famous, photographer husband, Alfred Stieglitz, who was the first to authorize her work in 1919. O’Keeffe’s marriage to Stieglitz is similar to the marriage between Kahlo and Rivera, since both women were married to men, and famous artists, who facilitated in bringing their artwork to a larger audience in a world that still viewed women as socially inferior. Nowadays, much of O’Keeffe’s work can be found in the Tate Modern, located in London, England, which showcases international modern and contemporary art. Achim Borchart Hume, who is the museum’s director of exhibitions, stated the reasoning behind the showcasing O’Keeffe’s work to be “Many of the white male artists across the 20th century have the privilege of being read on multiple levels, while others—be they women or artists from other parts of the world—tend to be reduced to one conservative reading. It’s high time that galleries and museums challenge this” (Ellis—Petersen 1). Hume makes a valid point in arguing that in order for women, or other artists that are not white males, to truly gain professional prestige in the artistic world, their work needs to be both prominent and show cased for long periods of time in museums and collections.

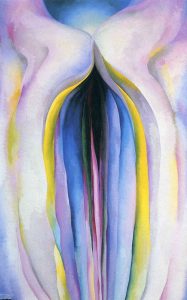

O’Keeffe’s Grey Lines With Black, Blue, and Yellow is an example of one of her many flower paintings that received a great amount of success during her career. The piece is slightly abstract since it is difficult to tell whether O’Keeffe is attempting to portray a form of plant life or female genitalia. This debate over what O’Keeffe is actually trying to convey is extended by the intentional use of three-dimensional lines that shape what is to be viewed as either a flower or a vagina. The colors within the painting, blues, greys, purples, black, and yellows are contrasting yet both euphoric and lustful. If O’Keeffe were alive to explain her symbolic intentions, she most definitely would claim that the piece has no sexual implications, but instead represents natural elements of the world she lived in (Ellis—Petersen 1). Furthermore, it is important to note that her husband, Alfred Stieglitz, introduced the interpretation of O’Keeffe’s work to resemble the female anatomy when he was beginning to publicize her art. However, since Stieglitz was the mind behind the symbolism of O’Keeffe’s flowers, and the fact that O’Keeffe refused to identify with any feminist labels, this acts as substantial evidence that O’Keeffe may simply have been just painting images of nature. Nonetheless, this does not diminish from the idea that her work represents feminist values since her accomplishments as a female artist in the 20th century were monumental. Her piece, Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1, was sold for $44.4 million dollars three years ago, making the painting the most costly work of art sold that was created by a female artist (Ellis-Petersen 1). O’Keeffe is quoted, “Men put me down as the best woman painted…I think I’m one of the best painters”, which attributes to her lack of conformity and confidence that inspired many eager, working females (The Tate Modern 1). Like Kahlo, O’Keeffe’s independent behavior and artistic content sparked the transition of her paintings being showcased in galleries and museums, to being nationally distributed, as well as creating a name recognition and becoming a prominent artistic figure. Similar to Kahlo, O’Keeffe’s relationship with Stieglitz was very open; therefore, O’Keeffe experienced a great deal of pain from his adultery. O’Keeffe’s independent behavior is demonstrated by her own affairs and her bisexuality. There is rumor that one of O’Keeffe’s affairs was with Kahlo, but nonetheless, this sort of behavior was beyond the traditional etiquette of women in the 1930’s and gave O’Keeffe a great deal of popularity (The New York Times 1). Furthermore, O’Keeffe’s independent sexuality is another characteristic that adds to the interpretation of her as a feminist. All in all, it is important to understand that although an artist may have a certain intention in mind, the audiences’ interpretation is what determines the final reputation of the piece. Because O’Keeffe’s paintings were seen as feminist, this allowed her to artwork to inadvertently become forms of public art, through advertisement and merchandise, as well as represent the thriving feminist movement, even though this was never her deliberate intention.

Contrasting from both Kahlo and O’Keeffe, Suzanne Lacy was neither commissioned by galleries nor museums, but instead impacted audiences on a local level by showcasing her art in largely public facilities (Fryd 23). Lacy’s most recognized example of public art is found in her exhibition, Three Weeks In May. Lacy’s intention behind the three week long display was to expose the frequency of rape, abuse, and sexual assault of women in Los Angeles. According to Vivien Green Fryd in her analysis of Three Weeks In May, Lacy “marked the establishment of New Genre Public Art, a socially engaged, interactive cultural practice that deploys a range of traditional and nontraditional media in public spaces for public audiences, intersecting activism, education, and theory” (Fryd 23). The difference between Lacy from Kahlo and O’Keeffe is that Lacy’s feminism was intentional. Furthermore, it did not take Lacy years for her artwork to gain recognition, unlike Kahlo and O’Keeffe, since her work consisted strictly of public art and was already available to so many people. Taking place in The City Mall Shopping Center, Lacy was strategic in her choice of setting because the location was near the Los Angeles City Hall. The notion to place the art in a public mall was to enlarge and diversify the audience Lacy hoped to connect with, primarily being women. Her dedication to feminism as well as political activism drove Lacy to want to attack, as well as assemble, governmental power and protest gender patterns.

The three images above represent the content in which Lacy included in her exhibition, Three Weeks In May. The first image showcases the street art that Lacy created to emphasize the reality of rape and how close it can be citizens in any community. The second image was showcased inside the City Mall Shopping Center and consists of a map and all of the areas in which women were raped spray painted in red. Lacy added to the spray painted labels as she checked the police reports daily for more cases of sexual assault against women (Fryd 23). The final picture exposes on the ignorance of society in the blindfolding of the female model, emphasizing Lacy’s political activism as one of her goals of Three Weeks In May was to spark a reaction from local institutions. Lacy’s work is highly applauded as she worked to raise awareness about many areas in society such as education and the suppression of minorities. Had it not been for her provocative, relevant content, as well as the being in the context of the women’s rights movement and other social movements, Lacy’s work would not have been as highly acclaimed. Lacy has won awards such as the Women’s Caucus for Art Lifetime Achievement Award, proving that her social work and artwork impacted a number of audiences (National WCA 1). However, Lacy’s artwork was not limited to paintings and other forms of public art, for she was also the author and editor of many books, such as Mapping The Terrain.

Mapping the Terrain is a book edited by Suzanne Lacy, consisting of eleven different authors, that discusses the new genre public art. “The term ‘new genre’ has been used since the late sixties to describe art that departs from traditional boundaries of media. Installations, performances, conceptual art, and mixed-media art, for example, fall into the new genre category, a catchall term for experimentation in both form and content” (Lacy 20). Lacy’s portion of the book is called “Cultural Pilgrimages and Metaphoric Journeys”, as she conveys the progression of the public art movement, as well as the importance of the history of art, and engaging multiple audiences to have success. Furthermore, Lacy offers though-provoking points about the feminist art movement, which was her most passionate area of interest. To begin, Lacy suggests that many public artists are predominately political activists, meaning that the more women understood themselves and their social identity, the more they created art about their experiences with gender inequality (Lacy 26). “The personal is political” is what Lacy stated to be the slogan of the feminist movement, implying that the personal inferiority women felt to men demands a political response (Lacy 27). Furthermore, towards the end of the 1970s, the feminist art movement was beginning to gain professional prestige, so many female artists collaborated with both men and women of minority social and economic groups so create an even larger political message that strived for equality (Lacy 27). Lacy includes a quote from Juana Alicia, a muralist, that reads, “I feel a great urgency in my own work to address the issues of our destruction and not make works of art that keep our society dormant”. Alicia’s words offer the reasoning behind new genre public art, to bring important issues to the general public, and inspire social change. All in all, Lacy’s editing of Mapping The Terrain shows that she was not limited artistically to Three Weeks In May. The political message behind the book clearly portrays that Lacy, on top of being an artist, was an activist and truly had the interest of gender equality at heart.

In conclusion, the fact that Kahlo, O’Keeffe, and Lacy’s work was so controversial and outspoken against gender norms allowed their artwork to be featured in numerous galleries, museums, and public venues. While Kahlo and O’Keeffe did not intentionally include feminist themes in their work, the artwork of all three women is bound by the common notion of challenging gender norms and furthering women’s rights. It is important to consider who authorizes public art, as well as who supports it, but it is also important to understand the difference between public artists versus public art. While public art is not necessarily limited to art on or inside public buildings, its genre is very specific. Kahlo and O’Keeffe did not create forms of public art, but are widely known artists because of their original content and vast reproduction of their work around the world. Every form of art’s purpose is to influence an audience, and while Kahlo, O’Keeffe, and Lacy’s genres differ, they are united by this artistic goal. The impact that these three women had on society is to grand for words. However, it is important to have an appreciation for Kahlo, O’Keefe, and Lacy’s bravery to be their own individual in a world that did not accept (and still does not accept to an extent) women as equal citizens capable of achieving goals just as well as men. Their paintings and artwork spoke to an audience that had no voice, which deserves greater applaud than earning a generous paycheck in the workforce. Who authorizes art, who supports it, as well as the dynamic of society as a whole will change as time goes on, but the goal of any artist will remain the same—to impact their viewers—no matter in what setting or form it exists

Works Cited

Brand, Peg. “Feminist Art Epistemologies: Understanding Feminist Art.” Hypatia 21.3 (2006): 166-89. Web. 9 Feb. 2017. Feminist Art Epistemologies: Understanding Feminist Art was used to understand the characterization of feminist art. Feminist art can be presented in many shapes, colors, and themes; however, it is the intention of the artist that makes the piece feminist or not. Feminist Art Epistemologies: Understanding Feminist Art made this understanding of an artist’s intention possible.

Bury, Liz. “Beyoncé Samples Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Call to Feminism.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 13 Dec. 2013. Web. 15 Mar. 2017. This site was strictly used to find the exact quote by Chimamanda Nigozi Adiche. Otherwise, this article served no purpose in the actual research for the paper.

Ellis-Petersen, Hannah. “Flowers or Vaginas? Georgia O’Keeffe Tate Show to Challenge Sexual Cliches.” The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 01 Mar. 2016. Web. 03 Mar. 2017. The Guardian article was used for a lot of the analysis of O’Keeffe’s life, including who authorized her artwork and who supported it. Furthermore, much of the article discussed how O’Keeffe inadvertently created feminist art, which was one of the main points made in the research paper.

Fryd, Vivien Green. “Suzanne Lacy’s Three Weeks in May: Feminist Activist Performance Art as “Expanded Public Pedagogy”.” NWSA Journal 19.1 (2007): 23-38. Web. 2 Mar. 2017. This journal article was used to gain a further understanding of the premise of Suzanne Lacy’s Three Weeks In May, as well as understand the effects the exhibition had on its viewers and the political message the art wished to expose.

“‘Georgia O’Keeffe: A Life’.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 02 Dec. 1989. Web. 15 Mar. 2017. This New York Times article was used to learn about O’Keeffe’s individual behavior in order to compare her actions to Frida Kahlo. Here, it was discovered that O’Keeffe was bisexual, and may have had an affair with Kahlo. Furthermore, this article assisted in furthering the argument that it is possible to characterize O’Keeffe as a feminist, even though she was against the label.

Lacy, Suzanne. Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art. Seattle, Wash: Bay, 1996. Print. Mapping the Terrain was used to offer another example of Lacy’s work that expanded beyond public art. Furthermore, the book provided a number of thought- provoking quotes and ideas regarding the feminist art movement, and the emotional and political effects such a movement had on the general public.

Prignitz-Poda, Helga, and Ingried Brugger. Frida Kahlo Retrospective. Berlin: Prestel, 2010. Print. Frida Kahlo Retrospective was used primarily for the analysis of Kahlo’s two paintings, Henry Ford Hospital (1932) and A Few Small Nips.

Tate. “Georgia O’Keeffe – Exhibition at Tate Modern.” Tate. N.p., n.d. Web. 03 Mar. 2017. The Tate Modern website was used to solidify that O’Keeffe’s work was being presently and consistently shown, as well as depict the importance of authorizing and supporting female artists.

“WCA Past Honorees.” WCA Past Honorees. N.p., n.d. Web. 15 Mar. 2017. This website was used to found out what awards Suzanne Lacy has won in the past. In providing the information that Lacy won the WCA in 2012, it emphasizes how appreciated and applauded her work was.