- Charters, John. An Account of the H.M.S. Enterprise, April 29, 1848-November 9, 1849. [Stefansson Manuscript 252]

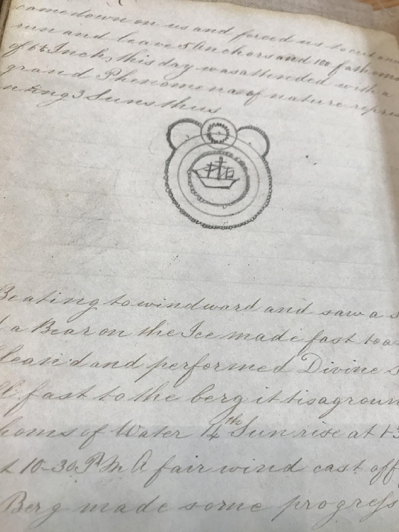

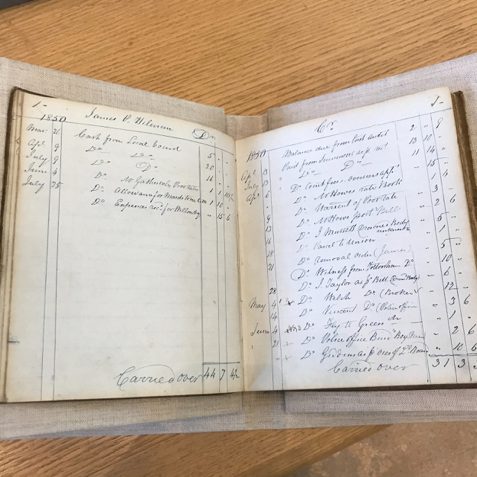

This is the journal of John Charters, a seaman on board the HMS Enterprise. It is a rare example of a shipboard journal in this period by a non-officer, providing the perspective of a seaman on board the Enterprise in search for Franklin and his men. The entries are written between April 29, 1848 until November 49, 1849. Captain Ross did not submit his account of the expedition, so there is no official report of the search. One of the pages in the journal shows an arctic natural phenomenon that Charters experienced in the expedition. It is showing the illusion of there being three suns as it occurs within the Arctic. Charters writes “this day was attended with a grand phenomenon of nature representing three suns.” The journey only lasted a year and though it was not successful in finding Franklin and his men, it resulted in the Europeans learning more about the Arctic and its different characteristics. The year after the expedition ended, the back of the journal was used as a legal ledger from 1850 until 1851, and it shows transactions and money exchanged.

This is the journal of John Charters, a seaman on board the HMS Enterprise. It is a rare example of a shipboard journal in this period by a non-officer, providing the perspective of a seaman on board the Enterprise in search for Franklin and his men. The entries are written between April 29, 1848 until November 49, 1849. Captain Ross did not submit his account of the expedition, so there is no official report of the search. One of the pages in the journal shows an arctic natural phenomenon that Charters experienced in the expedition. It is showing the illusion of there being three suns as it occurs within the Arctic. Charters writes “this day was attended with a grand phenomenon of nature representing three suns.” The journey only lasted a year and though it was not successful in finding Franklin and his men, it resulted in the Europeans learning more about the Arctic and its different characteristics. The year after the expedition ended, the back of the journal was used as a legal ledger from 1850 until 1851, and it shows transactions and money exchanged.

- Goodsir, Robert Anstruther. An arctic voyage to Baffin’s Bay and Lancaster Sound, in search of friends with Sir John Franklin. London: J. Van Voorst, 1850. (foldout map) [Stefansson G665 1849 .P4]

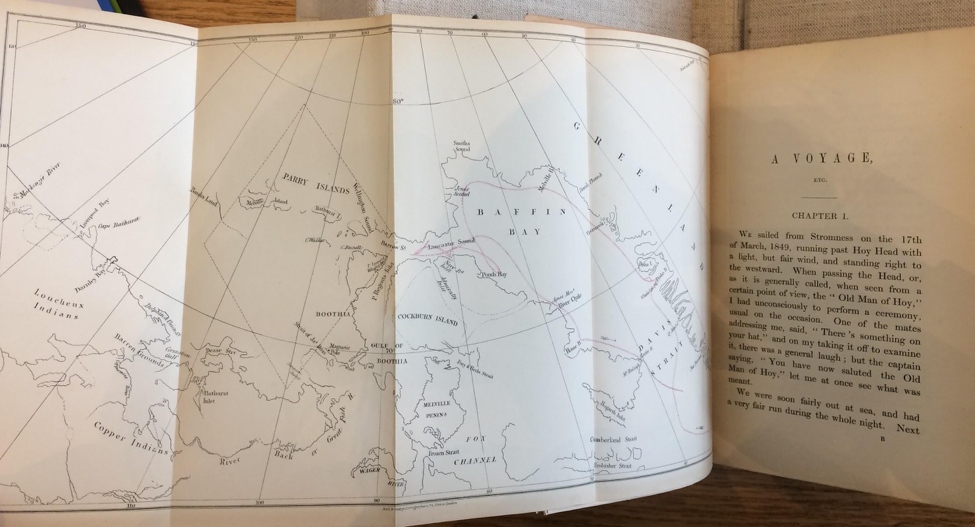

Robert Anstruther Goodsir’s short book describes an arctic expedition in search of Franklin’s fate. Goodsir’s brother Harry was a member of Franklin’s crew. Early in the text, Goodsir expresses gratitude towards Lady Franklin for encouraging the search. His expedition began in the spring of 1849, and the book includes stories of their route, struggles, and arctic insights they gained along the way. Goodsir provides accurate depictions of the wildlife and “Esquimaux” encounters. In the end, Goodisr’s expedition was unsuccessful at finding evidence of Franklin. Goodsir’s first question upon his return was “has anything been heard of Sir John Franklin?” and he stated he was “instantly depressed” upon hearing that no news had been found since the Esquimaux report which declared Franklin’s safety (151).

Robert Anstruther Goodsir’s short book describes an arctic expedition in search of Franklin’s fate. Goodsir’s brother Harry was a member of Franklin’s crew. Early in the text, Goodsir expresses gratitude towards Lady Franklin for encouraging the search. His expedition began in the spring of 1849, and the book includes stories of their route, struggles, and arctic insights they gained along the way. Goodsir provides accurate depictions of the wildlife and “Esquimaux” encounters. In the end, Goodisr’s expedition was unsuccessful at finding evidence of Franklin. Goodsir’s first question upon his return was “has anything been heard of Sir John Franklin?” and he stated he was “instantly depressed” upon hearing that no news had been found since the Esquimaux report which declared Franklin’s safety (151).

- Snow, William Parker. The Voyage of the Prince Albert in search of Sir John Franklin: a narrative of every-day life in the Arctic seas. Paris, A. and W. Galignani, 1851. (illustration of gutta percha boat) [Stefansson G 665 1850 .P91]

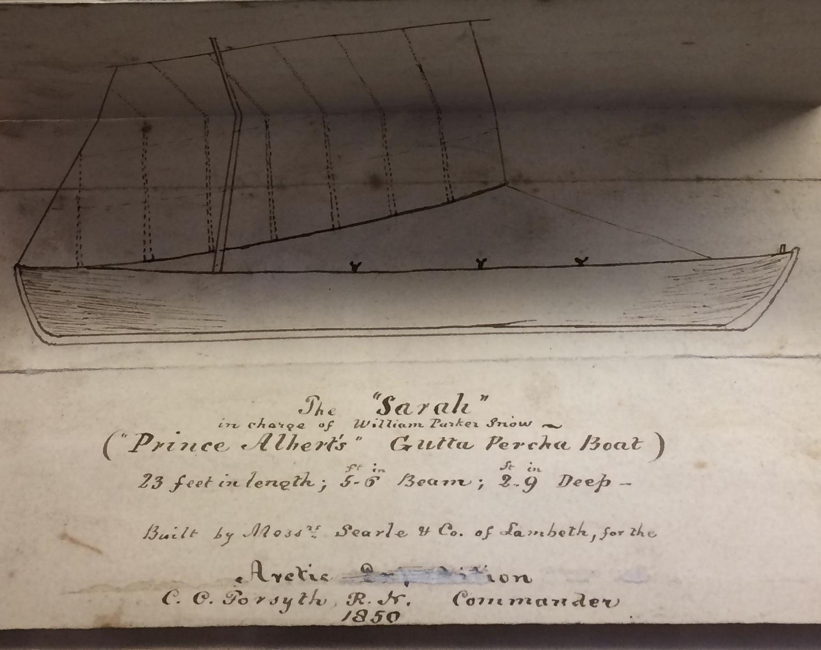

The Voyage of the Prince Albert highlights one of several expeditions sent out in order to find Sir Franklin and his crew. Included in this book are several sketches that provided information on the conditions and tools available during this attempted search as well as maps that marked the path taken by the Prince Albert. The Sarah, the Prince Albert’s Gutta Percha Boat, was integral in navigating through the icy waters of the Arctic, as it searched for the missing ships from Sir Franklin’s expedition.

The Voyage of the Prince Albert highlights one of several expeditions sent out in order to find Sir Franklin and his crew. Included in this book are several sketches that provided information on the conditions and tools available during this attempted search as well as maps that marked the path taken by the Prince Albert. The Sarah, the Prince Albert’s Gutta Percha Boat, was integral in navigating through the icy waters of the Arctic, as it searched for the missing ships from Sir Franklin’s expedition.

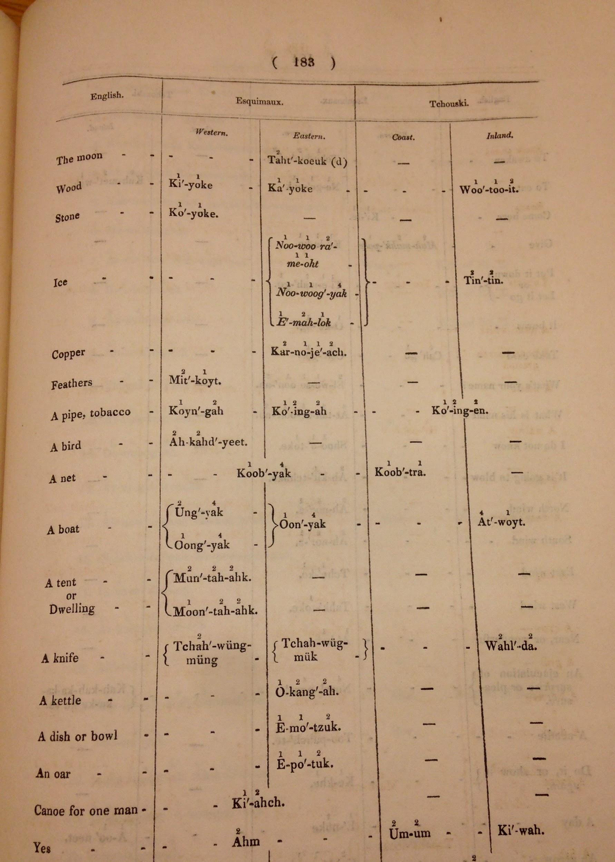

- Hooper, William Hulme. Ten months among the tents of the Tuski: with incidents of an Arctic boat expedition in search of Sir John Franklin, as far as the Mackenzie River, and Cape Bathurst. London: John Murray, 1853. (pg. 183) [Stefansson G665 1848 .M8]

This is a section of Lieutenant W. H. Hooper’s chart, “List of Esquimaux Words.” Hooper’s journal entries, including this chart, are located in the second section of the book Arctic Expeditions in Search of John Franklin, which was presented to the British Parliament in 1852. Hooper compiled this list between 1849 and 1850, while he was making his way from Fort Macpherson to Fort Simpson. He and his small crew of Englishmen relied on the assistance of various “Indian guides” to get them across the Canadian Arctic. In 1851, a correspondence from Hooper revealed his purpose for creating the chart: the lieutenant made an offer of service to further explore for Franklin, recommending a crew composed entirely of Inuit. He hoped that as the Indians had assisted his crew before, the Inuit’s knowledge of the land would be an invaluable asset. Faced with the daunting task of locating Franklin and his expedition, and the failure to do so thus far, Hooper believed new methods were required to find success.

This is a section of Lieutenant W. H. Hooper’s chart, “List of Esquimaux Words.” Hooper’s journal entries, including this chart, are located in the second section of the book Arctic Expeditions in Search of John Franklin, which was presented to the British Parliament in 1852. Hooper compiled this list between 1849 and 1850, while he was making his way from Fort Macpherson to Fort Simpson. He and his small crew of Englishmen relied on the assistance of various “Indian guides” to get them across the Canadian Arctic. In 1851, a correspondence from Hooper revealed his purpose for creating the chart: the lieutenant made an offer of service to further explore for Franklin, recommending a crew composed entirely of Inuit. He hoped that as the Indians had assisted his crew before, the Inuit’s knowledge of the land would be an invaluable asset. Faced with the daunting task of locating Franklin and his expedition, and the failure to do so thus far, Hooper believed new methods were required to find success.

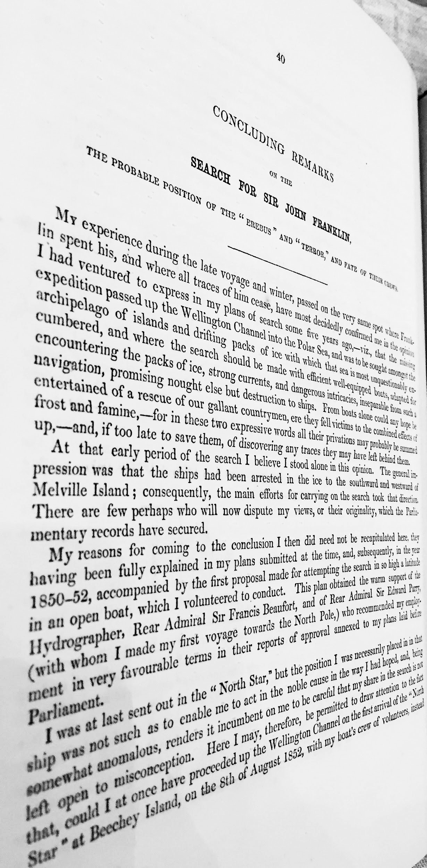

- McCormick, R. M. (Robert M.). Narrative of a boat expedition up the Wellington Channel in the year 1852, under the command of R. M’Cormick, …, in H.M.B.”Forlorn Hope,” in search of Sir John Franklin. London: Printed by G.E. Eyre and W. Spottiswoode, 1854. (pg. 40) [Stefansson G665 1852 .M2]

This book details the probable position of the Erebus and Terror, and the fate of their crews. It also provides a primary account of McCormick’s voyage in the search for Sir John Franklin, including charts, illustrations, narratives, and plans of search. Printed for the wealthy, it was published in London for the Queen’s “most excellent majesty.” McCormick narrates the boat expedition up the Wellington Channel in the year 1852 in the H.M.B Forlorn Hope. The purpose of his expedition was not to find Franklin and his crew alive, but rather to discover any traces of what they left behind. The last few pages of the book contain McCormick’s suggestions for the preservation of health in polar climates. He adds this because he feels that it is his duty to guide future voyagers, as he managed to maintain his health throughout his voyage.

This book details the probable position of the Erebus and Terror, and the fate of their crews. It also provides a primary account of McCormick’s voyage in the search for Sir John Franklin, including charts, illustrations, narratives, and plans of search. Printed for the wealthy, it was published in London for the Queen’s “most excellent majesty.” McCormick narrates the boat expedition up the Wellington Channel in the year 1852 in the H.M.B Forlorn Hope. The purpose of his expedition was not to find Franklin and his crew alive, but rather to discover any traces of what they left behind. The last few pages of the book contain McCormick’s suggestions for the preservation of health in polar climates. He adds this because he feels that it is his duty to guide future voyagers, as he managed to maintain his health throughout his voyage.

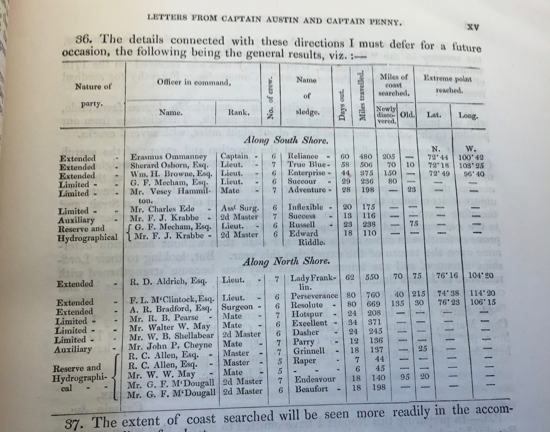

- [Arctic expeditions in search of Sir John Franklin] [1852]. (pg. xv) [Stefansson G601 .G7 1852]

A table, found in the book Arctic Expeditions in Search of John Franklin, contains details about the expeditions in search of Sir John Franklin throughout the northeast Canadian Arctic. This includes the group traveling, the length of the expedition, the distance traveled, and location coordinates. Taken together, this information provides a simple glimpse at a range of arctic expeditions, and allows for their success to be compared against one another. As these searches were intended to locate Sir John Franklin, the government organization and detail speaks for how determined people were to find their lost arctic hero. Ultimately, they would not have been successful, but this chart provides specifics needed to fill in the gaps in this crucial chapter in arctic exploration.

A table, found in the book Arctic Expeditions in Search of John Franklin, contains details about the expeditions in search of Sir John Franklin throughout the northeast Canadian Arctic. This includes the group traveling, the length of the expedition, the distance traveled, and location coordinates. Taken together, this information provides a simple glimpse at a range of arctic expeditions, and allows for their success to be compared against one another. As these searches were intended to locate Sir John Franklin, the government organization and detail speaks for how determined people were to find their lost arctic hero. Ultimately, they would not have been successful, but this chart provides specifics needed to fill in the gaps in this crucial chapter in arctic exploration.

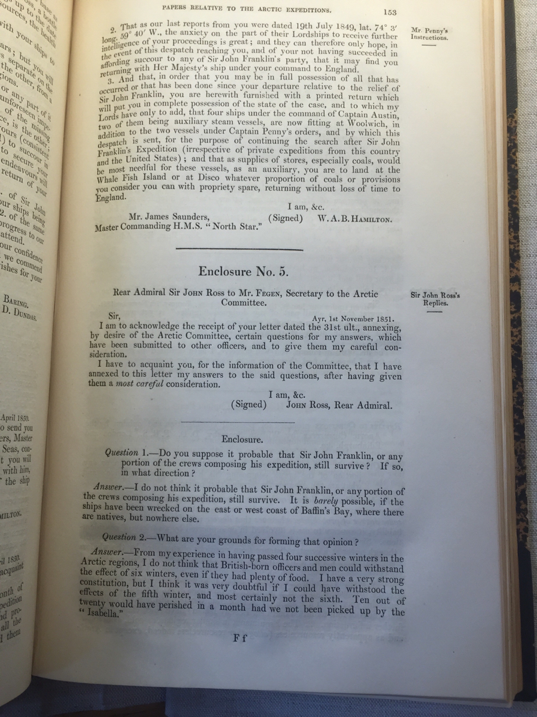

- Mangels, James. Papers and despatches relating to the Arctic searching expeditions of 1850-51-52: together with a few brief remarks as to the probable course pursued by Sir John Franklin. London: F. & J. Rivington, 1852. (pgs. 153-154) [Stefansson G665 1851 .M3]

This book includes the written testimony of Rear Admiral John Ross, in response to several questions asked of him regarding his opinions on the potential status of the Franklin expedition, and whether it was of benefit to continue search efforts. This testimony comes from the report commissioned by the Lords Commissioners of the High Admiralty in 1851 regarding the Franklin expedition and the early search operations, and was a part of the calculations that led to the British continuing naval operations in hopes of finding Franklin. Sir Ross was a noted arctic explorer who had spent a great deal of time in the area of the Northwest Passage, and who had led a recent search effort for Franklin, making him an ideal resource for the Admiralty to consult.

This book includes the written testimony of Rear Admiral John Ross, in response to several questions asked of him regarding his opinions on the potential status of the Franklin expedition, and whether it was of benefit to continue search efforts. This testimony comes from the report commissioned by the Lords Commissioners of the High Admiralty in 1851 regarding the Franklin expedition and the early search operations, and was a part of the calculations that led to the British continuing naval operations in hopes of finding Franklin. Sir Ross was a noted arctic explorer who had spent a great deal of time in the area of the Northwest Passage, and who had led a recent search effort for Franklin, making him an ideal resource for the Admiralty to consult.

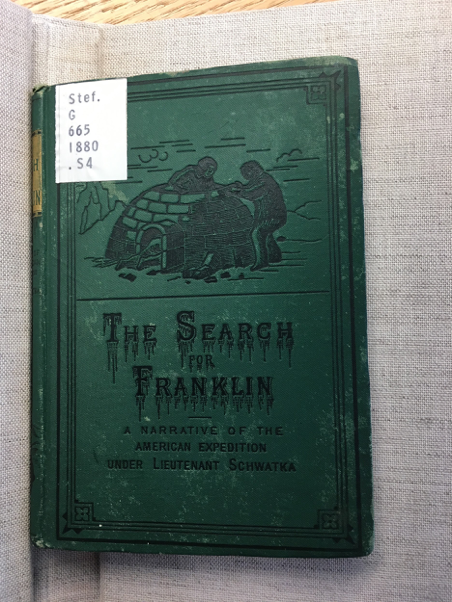

- The search for Franklin; a narrative of the American expedition under Lieutenant Schwatka, 1878 to 1880. London: T. Nelson, 1882. (book cover, title page) [Stefansson G665 1880 .S4]

This is an account by Lieutenant Schwatka, an American officer, on his journey to the Arctic to search for Franklin. He sought to confirm previous accounts of finding evidence of Franklin’s expedition in the region of King William Land. Judging from the book’s cover and illustrations, it’s obvious that this account was meant to capture the public’s attention as an arctic adventure and thriller. The cover image and font plays on one’s imagination of a foreign, remote region where igloos and Inuit are the only signs of civilization.

This is an account by Lieutenant Schwatka, an American officer, on his journey to the Arctic to search for Franklin. He sought to confirm previous accounts of finding evidence of Franklin’s expedition in the region of King William Land. Judging from the book’s cover and illustrations, it’s obvious that this account was meant to capture the public’s attention as an arctic adventure and thriller. The cover image and font plays on one’s imagination of a foreign, remote region where igloos and Inuit are the only signs of civilization.