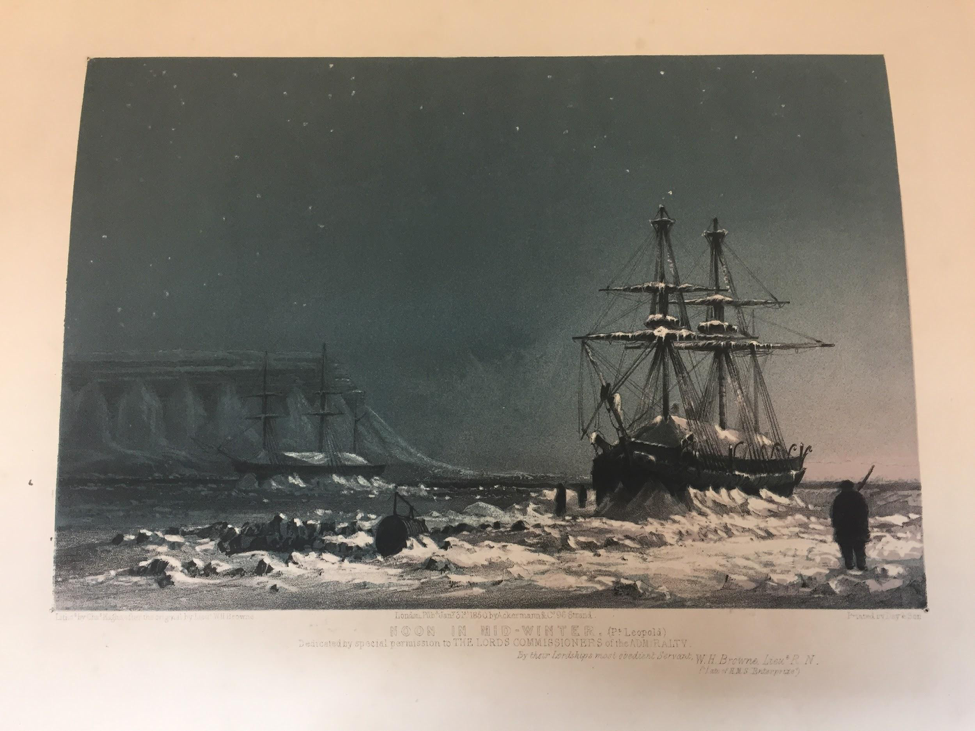

- Browne, W. H. Ten coloured views taken during the Arctic expedition of Her Majesty’s ships “Enterprise” and “Investigator,” under the command of Captain Sir James C. Ross. London: Ackermann, 1850. (final image) [Stefansson G610 .B88]

The final image from “Ten coloured views taken during the Arctic expedition of Her Majesty’s ships ‘Enterprise’ and ‘Investigator’” depicts “Noon in Mid-Winter.” The book is a stunning collection of drawings by W. H. Brown released with a concise summary in both English and French of “the various Arctic expeditions in search of Captain Sir John Franklin, K. T., K. C. H., and his companions in H. M. ships ‘Erebus’ and ‘Terror’” (1). The book was reserved for the wealthy as a way to repay those who had financed the arctic expeditions in the past as well as to advertise for future support of arctic explorations. It was used to keep the wealthy public informed of what had happened to their finances and where they could be applied in the future through striking colored images of what life was like in the Arctic on these voyages.

The final image from “Ten coloured views taken during the Arctic expedition of Her Majesty’s ships ‘Enterprise’ and ‘Investigator’” depicts “Noon in Mid-Winter.” The book is a stunning collection of drawings by W. H. Brown released with a concise summary in both English and French of “the various Arctic expeditions in search of Captain Sir John Franklin, K. T., K. C. H., and his companions in H. M. ships ‘Erebus’ and ‘Terror’” (1). The book was reserved for the wealthy as a way to repay those who had financed the arctic expeditions in the past as well as to advertise for future support of arctic explorations. It was used to keep the wealthy public informed of what had happened to their finances and where they could be applied in the future through striking colored images of what life was like in the Arctic on these voyages.

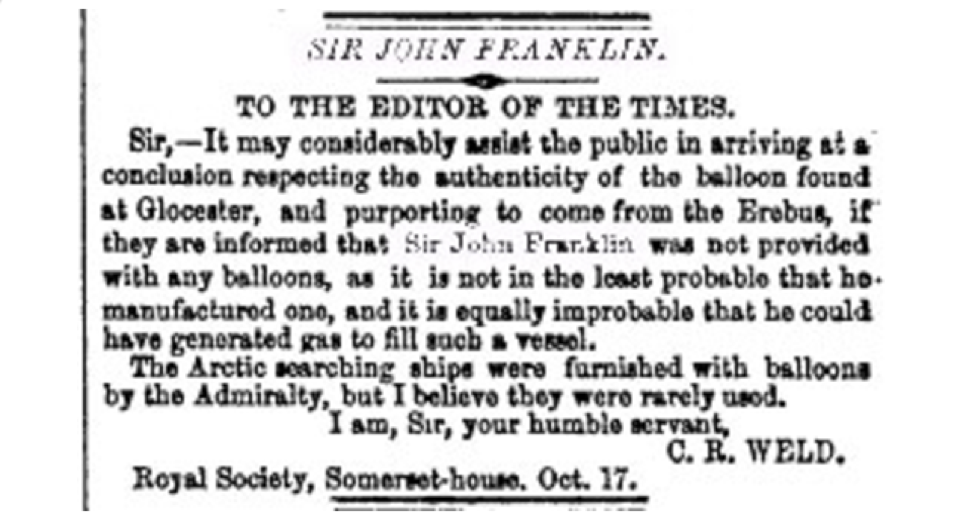

- Weld, C.R. “Sir John Franklin: Letter to the Editor of the Times”, London Times, 1851.

In 1851, a woman named Mrs. Russell claimed to see a government-issued, Arctic-messaging balloon land in her garden. The balloon contained coordinates of Sir John Franklin and his crewmembers. These balloons were difficult to acquire, thus the message appeared credible and newspapers took an immediate interest. C.R. Weld, the main assistant to Sir John Franklin in the organization of his arctic expeditions, writes to the editor of the London Times on October 17th, 1851 to discredit the authenticity of the balloon. During the years Franklin was missing, many other items were rumored to have come from his ship, but like the balloon, they were proven fake.

In 1851, a woman named Mrs. Russell claimed to see a government-issued, Arctic-messaging balloon land in her garden. The balloon contained coordinates of Sir John Franklin and his crewmembers. These balloons were difficult to acquire, thus the message appeared credible and newspapers took an immediate interest. C.R. Weld, the main assistant to Sir John Franklin in the organization of his arctic expeditions, writes to the editor of the London Times on October 17th, 1851 to discredit the authenticity of the balloon. During the years Franklin was missing, many other items were rumored to have come from his ship, but like the balloon, they were proven fake.

C.R. Weld’s letter to the London Times editor details a civilian-generated rumor about Sir John Franklin’s whereabouts. Because search expeditions needed new information regarding Franklin, rumors publicized by media had to be vetted before acted upon. C.R. Weld understood the Franklin expeditions better than anyone else and he helped combat rumors using his knowledge and scientific background.

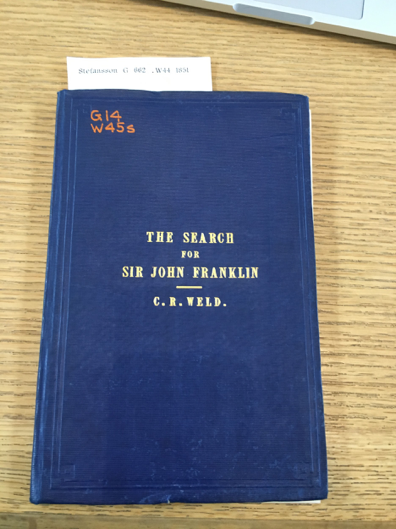

- Weld, Charles Richard. The search for Sir John Franklin. A lecture delivered at the Russell institution. January 15, 1851. London: R. Bentley, 1851. (book cover, title page) [Stefansson G662 .W44 1851]

This lecture describes Sir John Franklin’s final voyage in 1845 and the search expeditions that followed. C.R. Weld discusses major findings during the search for Franklin, and attempts to create a map based on these findings. He references many different expeditions and major names involved in the search, such as John Richardson, Captain Kellett, and Lady Franklin’s expeditions. He reveals his theory regarding Franklin’s whereabouts and activities during his final days, which he believed were on Cape Riley. Finally, he argues that if the conditions were tolerable, Franklin’s crew could survive. Based on this, he believes that the search should continue.

This lecture describes Sir John Franklin’s final voyage in 1845 and the search expeditions that followed. C.R. Weld discusses major findings during the search for Franklin, and attempts to create a map based on these findings. He references many different expeditions and major names involved in the search, such as John Richardson, Captain Kellett, and Lady Franklin’s expeditions. He reveals his theory regarding Franklin’s whereabouts and activities during his final days, which he believed were on Cape Riley. Finally, he argues that if the conditions were tolerable, Franklin’s crew could survive. Based on this, he believes that the search should continue.

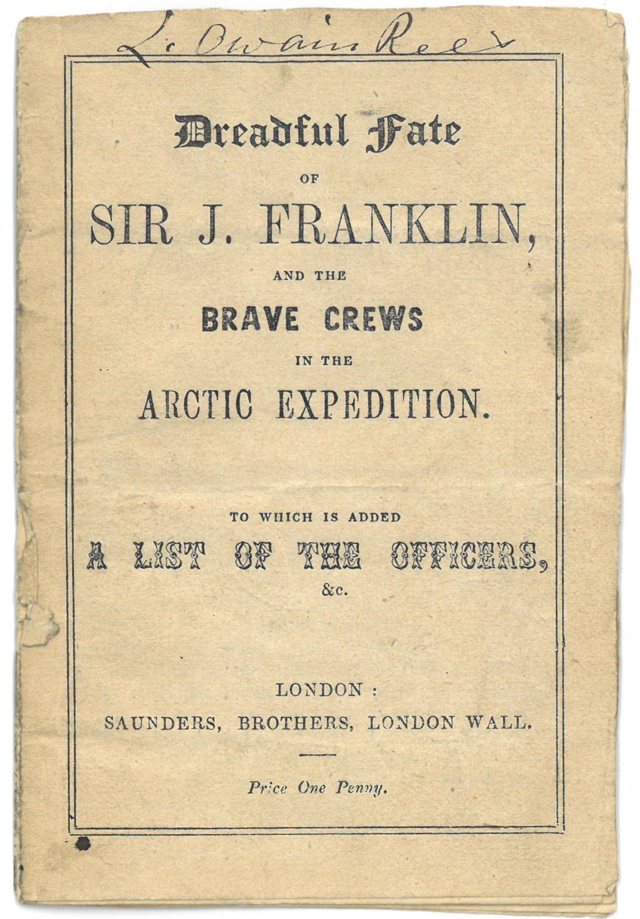

- Dreadful Fate of Sir J. Franklin. London: Saunders, [1854] (book cover) [Stefansson G660.D72]

This ‘penny dreadful’, a short story sold for a penny in England, covers Sir John Franklin’s expedition and the search for him following. Written in 1854, it gruesomely accounts finding the bodies of the men on the boats and interactions with Inuit people. It also talks about Dr. John Rae’s discovery, including quotes from a letter to the editor of the Times.

This ‘penny dreadful’, a short story sold for a penny in England, covers Sir John Franklin’s expedition and the search for him following. Written in 1854, it gruesomely accounts finding the bodies of the men on the boats and interactions with Inuit people. It also talks about Dr. John Rae’s discovery, including quotes from a letter to the editor of the Times.

- Sad Tidings of Sir John Franklin. [S.I.: s.n., 1854?]. [Stefansson Broadside 001402]

Sad Tidings of Sir John Franklin contains a letter from George Simpson, Governor of the Hudson’s Bay Territory, to Henry Grinnell, a New York aristocrat. Governor Simpson encloses an excerpt from the Montreal Herald‘s October 21st issue, which contains a letter Simpson received from Dr. Rae, in which the latter details his arctic voyage and its findings. Dr. Rae discovered secondhand accounts of cannibalism and death by starvation of some of Franklin’s crewmembers as well as several of their articles (primarily engraved silverware) that he obtained from Inuit. The purchased silverware, originally scavenged from the sites where the crewmembers perished, constituted the only substantive evidence of Franklin and his crew’s fate at the time. Note that Governor Simpson fully accepts Dr. Rae’s gruesome conclusions, as he assures Mr. Grinnell that “this information is no mere rumor,” by way of the physical proof. Perhaps the Governor’s experience of the region’s harsh conditions had an influence. However, Dr. Rae’s accounts would be less well-received in Britain, where its contents became a subject of controversy. His report would bring Franklin’s expedition back into the public eye and reignite the search for the missing crews, if only to discover their exact fate.

Sad Tidings of Sir John Franklin contains a letter from George Simpson, Governor of the Hudson’s Bay Territory, to Henry Grinnell, a New York aristocrat. Governor Simpson encloses an excerpt from the Montreal Herald‘s October 21st issue, which contains a letter Simpson received from Dr. Rae, in which the latter details his arctic voyage and its findings. Dr. Rae discovered secondhand accounts of cannibalism and death by starvation of some of Franklin’s crewmembers as well as several of their articles (primarily engraved silverware) that he obtained from Inuit. The purchased silverware, originally scavenged from the sites where the crewmembers perished, constituted the only substantive evidence of Franklin and his crew’s fate at the time. Note that Governor Simpson fully accepts Dr. Rae’s gruesome conclusions, as he assures Mr. Grinnell that “this information is no mere rumor,” by way of the physical proof. Perhaps the Governor’s experience of the region’s harsh conditions had an influence. However, Dr. Rae’s accounts would be less well-received in Britain, where its contents became a subject of controversy. His report would bring Franklin’s expedition back into the public eye and reignite the search for the missing crews, if only to discover their exact fate.

- Symboyleyomenoi, Philoi. The Great Arctic mystery. London: Chapman and Hall, 1856. (pg. 16) [Stefansson G662 .G73 1856]

This report outlines Dr. Rae’s claim towards one part of the reward for information on the Franklin Expedition, specifically the third part of the reward regarding information, “…by virtue of his or their efforts, first succeed in ascertaining their fate” (‘London Gazette’, 12/22/1856). Symboyleyomenoi chronicles how Rae gathered this information, and in his conclusion (the above page) makes the plea to the Admiralty that Rae not receive the £10,000 reward, nor that they adjudicate the reward to James Anderson (who led the expedition to try to validate Rae’s claim). If the Admiralty were to award one or both of the men with the reward money, they would be endorsing the fate of Franklin’s expedition, and would thus quench the fire that was the Search.

This report outlines Dr. Rae’s claim towards one part of the reward for information on the Franklin Expedition, specifically the third part of the reward regarding information, “…by virtue of his or their efforts, first succeed in ascertaining their fate” (‘London Gazette’, 12/22/1856). Symboyleyomenoi chronicles how Rae gathered this information, and in his conclusion (the above page) makes the plea to the Admiralty that Rae not receive the £10,000 reward, nor that they adjudicate the reward to James Anderson (who led the expedition to try to validate Rae’s claim). If the Admiralty were to award one or both of the men with the reward money, they would be endorsing the fate of Franklin’s expedition, and would thus quench the fire that was the Search.

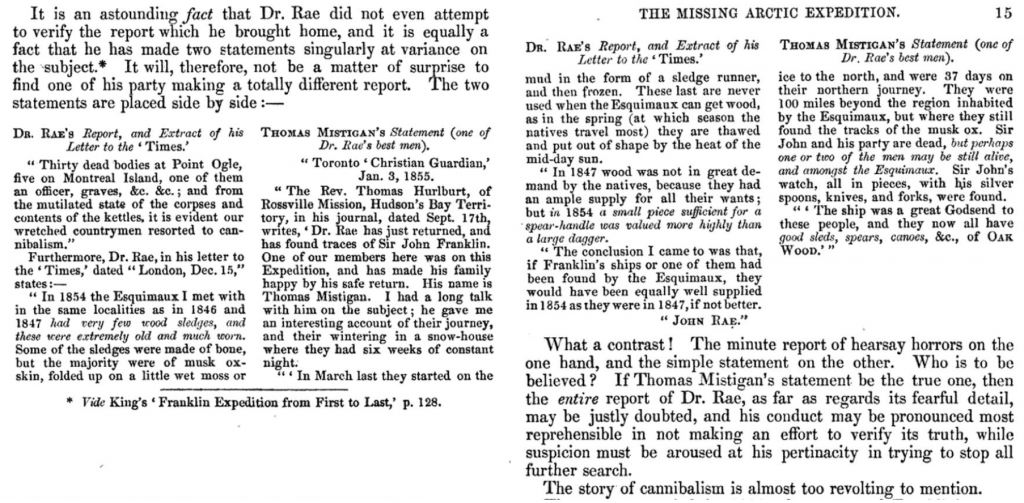

- Pim, Bedford. An Earnest Appeal to the British Public on Behalf of the Missing Arctic Expedition. London: Hurst and Blackett, 1857. (pg. 15) [Stefansson G660 .P6]

This is a piece of propaganda written by Lt. Bedford Pim in 1857. In it, the Royal Navy officer scrutinizes Dr. Rae’s reports of the fate of the Franklin Expedition, urging the public to discredit his accusations of cannibalism. He challenges Dr. Rae’s credibility in order to uphold the dignity of the British soldiers and officers who died on the Franklin expedition. It illustrates the confusion and drama that the search and discovery of the Franklin expedition created for the general public. There was clearly a discrepancy between the public’s perception of Franklin’s fate and of those actively searching and discovering it. This pamphlet is an obvious example at an attempt to hide the gruesome facts from the public and maintain the pristine reputation of the British army.

This is a piece of propaganda written by Lt. Bedford Pim in 1857. In it, the Royal Navy officer scrutinizes Dr. Rae’s reports of the fate of the Franklin Expedition, urging the public to discredit his accusations of cannibalism. He challenges Dr. Rae’s credibility in order to uphold the dignity of the British soldiers and officers who died on the Franklin expedition. It illustrates the confusion and drama that the search and discovery of the Franklin expedition created for the general public. There was clearly a discrepancy between the public’s perception of Franklin’s fate and of those actively searching and discovering it. This pamphlet is an obvious example at an attempt to hide the gruesome facts from the public and maintain the pristine reputation of the British army.

- F.W.I Arctic Stories, or Dr. Kane’s Search for Franklin. London: Gall & Inglis, 1887?. (book cover, title page) [Stefansson G614 .F85]

Written in third person POV, this children’s story about Dr. Kane’s trials and tribulations while searching for the lost Franklin ship and crew brings excitement, adventure, and wonderment to all children who read it. While written at an unknown date, it can be inferred that it was written around the 1850s-60s. In the book, F.W.I fictionalizes the true story of Dr. Kane’s search for Franklin and intersperses it with similar stories of other men’s adventures to the Great North, such as tales of close encounters with polar bears and ships crushed between ice bergs. While Kane was not successful in discerning the fate of Franklin, his story, nevertheless, shows the sense of bravery arctic travelers had and, more-so, the sense of immense adoration the British had for these travelers.

Written in third person POV, this children’s story about Dr. Kane’s trials and tribulations while searching for the lost Franklin ship and crew brings excitement, adventure, and wonderment to all children who read it. While written at an unknown date, it can be inferred that it was written around the 1850s-60s. In the book, F.W.I fictionalizes the true story of Dr. Kane’s search for Franklin and intersperses it with similar stories of other men’s adventures to the Great North, such as tales of close encounters with polar bears and ships crushed between ice bergs. While Kane was not successful in discerning the fate of Franklin, his story, nevertheless, shows the sense of bravery arctic travelers had and, more-so, the sense of immense adoration the British had for these travelers.