Redefining Public Art

Public art has long been a cultural tradition of societies across the globe. In fact, some anthropologists consider the ability to produce and share art a defining characteristic of the human race, pointing to the iconic cave drawings of primal humans as evidence of a key transition point in our evolutionary history (Kolbert 258). Since these ancient pictographs, public art has taken many different forms, from murals to graffiti and more. Although public art is generally defined as art that is open for free viewing from the general public, I also believe public art can be defined in another way. In my opinion, public art is also any art that is used to generate discussion and reflection among the public. Art that questions accepted realities and thus catalyzes change is often produced with public consumption in mind, and should also be considered a form of public art. Furthermore, art which is not sanctioned or commissioned by people with money and power perhaps resonates even more with this definition of public art since it is not contaminated by the deceptive intention of generating influence for the rich and powerful, and rather more concerned with inspiring social change. Artists such as Frida Kahlo circumvented the constraints that institutional authorization put on art by producing work with content that depended solely on her personal initiative, and not the agenda of the people signing her paychecks. This freedom of individual expression allowed Frida to produce provocative and influential paintings, such as Frida’ innumerable self-portraits, that defined this different type of public art.

Although Frida Kahlo did not produce public art in the traditional sense, the content of her art was her own prerogative and meant to be thought invoking for the viewer, making it public art in the way outlined above. Unlike the muralists of the time, the content of her work was exclusively her own decision and drew only from her own experiences and sentiments. The muralists depended on the commissions of government officials (such as Vasconcelos) or wealthy capitalists and thus were somewhat beholden to the agenda of the people signing their paychecks. The federal patronage of these great muralists led to the paradox of “a revolutionary art becom[ing] an official art that helped legitimize an authoritarian state” (Coffey 1) Frida’s lack of popularity during her time in some ways allowed her to be a truly revolutionary artist, even more so than the Tres Grandes because she had the free will to depict and legitimize the female experience in a world that primarily valued the male perspective. Frida herself acknowledges that “I paint…whatever passes through my head, without any other consideration” (Herrera xii). The liberated and revolutionary images she ended up producing would ultimately become symbols of the modern feminist movement for the way they questioned accepted realities of the female experience. These images were viewed by many and came to represent a public sentiment, despite their private ownership in some cases.

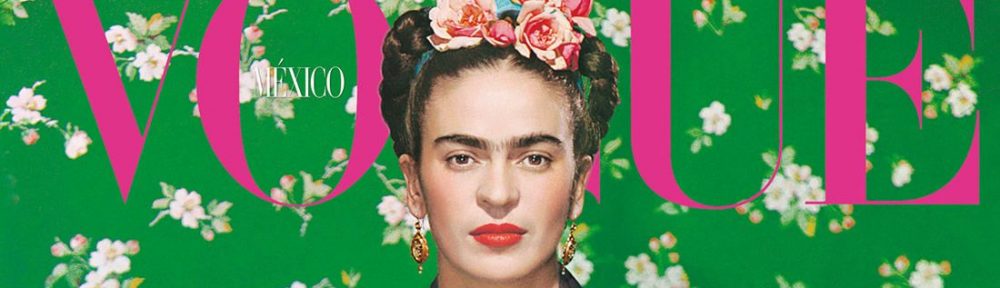

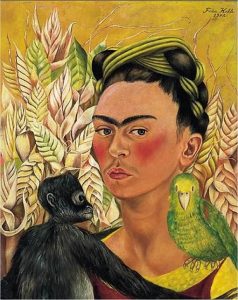

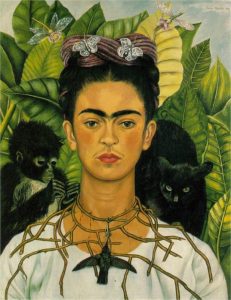

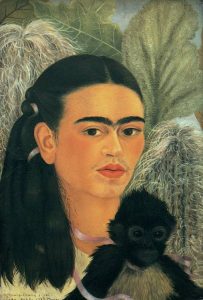

Thanks to the freedom of expression Frida experienced, her art was influential and provocative in many ways. Her influence is most notably evidenced by her surge in popularity in recent decades. In 1995, her painting “Self-Portrait with a Monkey and a Parrot” sold for $3.2 million, the highest price ever paid for a Latin-American work of art and the second-highest amount payed for a women artist (Collins). Frida’s popularity likely stems from the revolutionary nature of her art and life, and the feminist sentiments they inspire. In the heavily male dominated artistic narrative of post-revolutionary Mexico, Frida’s art offers a refreshing female perspective. Perhaps the most outwardly feminist theme of her art is the way she questions societal gender roles through sexual ambiguity in her self-portraits. For example, in her famous “Self-Portrait with a Monkey and a Parrot” mentioned above, Frida paints herself with obvious male features, such as a unibrow and mustache. Many of Frida’s other self-portraits also depict her with masculine features such “Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair” in which Frida is dressed in a man’s suit and boyish haircut after having cut off her long hair, a popular sign of Mexican womanhood and female beauty (Bakewell 169). Frida is often charged with exaggerating her facial hairs and masculine features in many of her other self-portraits in order to blur the line between male and female, as additionally evidenced by “Self Portrait with a Necklace and a Hummingbird” and “Fulang Chang and I” (Bakewell 169). In doing so, she not only attacks the patriarchy but also redefines beauty. As Carlos Fuentes eloquently puts it, “The manner of conceiving beauty as truth and self-knowledge…is Kahlo’s great legacy to the women of an increasing faceless, anonymous planet, where only the ‘photogenic’ or ‘shocking’, as seen on the screens, merits our vision” (Fuentes 17). Kahlo does not abide by conventional beauty standards, but this unconventional appearance and defiance is exactly what makes her beautiful. With a legacy of redefining beauty in the 21st century, her art inarguably makes the public question accepted realities and catalyzing change and thus should be considered a form of public art.

Not only is Frida Kahlo’s art public in many ways, it is also revolutionary. Perhaps the definition of public art I have been attempting to sell can be simplified: public art is art that is revolutionary. Revolutionary can be defined in many contexts and on my scales, but ultimately comes down to something that inspires people to think in different ways and reconsider often oppressive norms. Frida Kahlo’s art is undoubtedly revolutionary in the way she questions gender roles in society, regardless of the fact it is constrained to small canvases and does not take grand new forms such as murals. Revolutionary art is inherently dedicated to the public for its primary goal is to inspire change within its viewers. For art to be truly revolutionary is must be seen and seen by many to inspire the change that makes it so influential. Since her death, images of Frida Kahlo’s art have been viewed and enjoyed by millions of people due to their provocative and inspiring nature, making her self-portrait as recognizable as the face of a modern-day celebrity. Considering this, Frida’s art has undoubtedly achieved public and thus revolutionary status.