Marching Forward with Frida

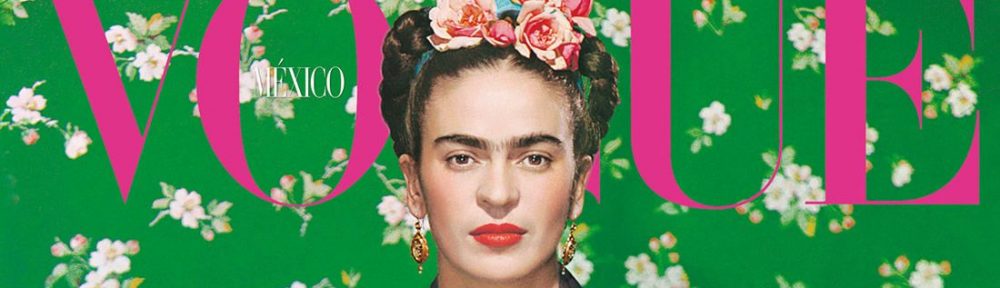

Frida Kahlo is undoubtedly a feminist icon of the late 20th and early 21st century. Her rediscovery and resulting explosion in popularity in the recent decades is not only noted by a significant increase in the market value of her artwork, but also by the mainstream recognition of her face. Images of Frida’s famous self-portraits with her striking eyes have been printed on everything from T-shirts to magnets to tennis shoes, demonstrating the “Fridamania” that has taken over the world. The image and idea of Frida has especially become linked with feminism, many seeing her life and work as a prime representation of the core ideals of the feminist movement. Although the specific goals of the feminist movement have differed over time, one easily identifiable goal being women’s suffrage, the basic tenants have remained the same. Women want equal opportunities and consideration in the political, professional, and educational realm. Feminists are people who “believe in the social, political and economic equality of the sexes” (Adichie 17). Frida is an early feminist due to her challenge of gender norms, her depiction of pain and suffering from a women’s perspective, and her commitment to spreading revolutionary ideals.

It is first important to contextualize Frida within the time period she lived and painted. Frida came of age in the early 1920s, which was right at the end of Mexican Revolution. At that time, post-revolutionary Mexico was defined by a political rhetoric that championed the previously marginalized (such as women and the mestizo) and promised a radical social transformation (Bakewell 167). However, although the Revolution was successful at overthrowing the oppressive dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, it was relatively unsuccessful at bringing about meaningful social and political change. This sentiment is well articulated in the “Hispano-America” panel in José Clemente Orozco’s mural Epic of American Civilization at Dartmouth College (Fig. 1). Orozco is considered one of the premier muralists of the post-revolutionary mural movement in Mexico. In this panel, we see a Mexican rebel being stabbed in the back by his own general. In the foreground, what appears to be greedy government officials hoard golden coins while other military officials clamor to get their own share of money. As evidenced by this mural, despite the utopic depictions of post-revolutionary Mexico in the murals of Diego Rivera, in this panel Orozco demonstrates how the Mexican government was still characterized by corruption and consolidation of power, with women and campesinos remaining to be marginalized (Bakewell 168). Unfortunately, the progressive political rhetoric of the Mexican Revolution did not precipitate real change for the roles of women in society, including Frida Kahlo.

In fact, the artistic world that was largely responsible for creating this new nationalist rhetoric was very much a male dominated space. The famous artists of the time, such as “Los Tres Grandes” that comprised of Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and Frida Kahlo’s husband, Diego Rivera, were tasked with using public murals to rebuild a national culture that celebrated indigeneity and inspired Mexican nationality. Frida was obviously intimately tied to the artistic world through her own artwork as well as marriage to Diego Rivera. Ironically however, Jose Vasconcelos, the Minister of Education after the Revolution, commissioned only male artists to construct these iconic murals (Pankl & Blake 5). In the process of trying to liberate one marginalized group of people, these male muralists solidified a male-centered artistic narrative.

In contrast, Frida’s art had a refreshing female perspective. Furthermore, unlike the muralists of the time, the content of her work was exclusively her own decision and drew only from her own experiences and sentiments. The muralists depended on the commissions of government officials, such as Vasconcelos, or wealthy capitalists and thus were somewhat beholden to the agenda of the people signing their paychecks. The federal patronage of these great muralists led to the paradox of “a revolutionary art becam[ing] an official art that helped legitimize an authoritarian state” (Coffey 1). Frida’s lack of popularity during her time in some ways allowed her to be a truly revolutionary artist, even more so than the Tres Grandes because she had the free will to depict and legitimize the female experience in a world that primarily valued the male perspective. Frida herself acknowledges that “I paint…whatever passes through my head, without any other consideration” (Herrera xii). The liberated and revolutionary images she ended up producing would ultimately become symbols of the modern feminist movement for the way they questioned accepted realities of the female experience. These images were viewed by many and came to represent a public sentiment, despite their private ownership in some cases.

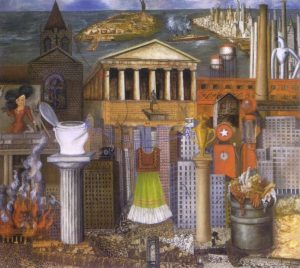

Frida’s commitment to the Communist party in her life and work demonstrate her political activism and ardent individualism. Frida was so committed to the ideals of the Revolution that she claimed she was born in 1910, instead of her real birth year 1907 (Pankl & Blake 4). She did this in order to label herself a daughter of the revolution. She was an active member of the Mexican communist party alongside her husband Diego Rivera, their shared revolutionary politics being a driving force behind their marriage (Bakewell 167). Frida’s socialist outlook is well demonstrated in My Dress Hangs There (Fig. 2), a painting she did while living in the United States with Diego in 1933. In the image, Frida’s traditional indigenous dress hangs on a wire across a modern America background. This background includes identifiable landmarks such as the statue of liberty and Manhattan island, celebrated symbols of American democracy and capitalism. In the forefront of the image however are images of what she perceives to be the harsh reality of democracy, including piles of garbage, tenement buildings, and a collage of newspaper clippings with headlines of social unrest. (Ankori 104). Coming from Mexico, a society where women were still not allowed to vote and the political arena was still very much a male domain, Frida “took to the streets in support of the communist revolutionary movements” (Bakewell 169). Her political activism inherent in her life and work demonstrates her feminist tendency to fight for gender equality in the political realm as well as the cultural.

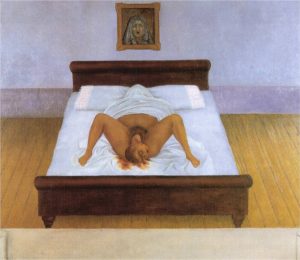

In addition to the explicit revolutionary and Communist content in Frida’s paintings, her art was also progressive and radical for the way it depicted the female body. The famous nude paintings drawn by Frida’s male contemporaries and predecessors were typically very objectifying of women, portraying their reclining bodies as lustful objects to be taken and enjoyed by men at their fancy. An example of the objectification of women that was popular at the time in many works of art are the Hovey Murals at Dartmouth College, which were painted by the white male artist, Walter Beach Humphrey in 1938 and which present a prime example of this tradition. In a particularly offensive panel, a group of Native American women are all gathered around naked looking at a central nude woman holding up a feathered fan (Fig. 3). There facial features are all similar, nondescript, and obviously Caucasian. Humphrey likely made their features white because he was accounting for the tastes of the perceived viewers, who in the late 1930s at Dartmouth College were predominantly the white, male students, faculty, and alumni, who would have used the Hovey Grill for their social gatherings, and who in 1938 would not have been bothered by these images that we now understand to be completely disrespectful of women. By doing so, Humphrey acknowledges that these portraits of nude women are meant for the visual pleasure of the males, completely disrespecting women as individuals and classifying them as objects of desire without capabilities beyond that of sexual pleasure. In striking contrast to the images that Hovey painted at Dartmouth College, “Frida’s nudes de-eroticize the female by representing blemished, imperfect, bloody bodies” (Bakewell 174). Many of her most famous paintings depict nude female bodies, most commonly brutally honest depictions of her own naked and broken body. What some argue is her most famous painting, My Birth is a graphic depiction of a naked women during child birth with a head coming out of her bloody vagina (Fig. 4). This is obviously not a sensual image, however it does depict an often censored reality of the female experience. Hayden Herrera claims it is “one of the most awesome images of childbirth ever made” (Herrera 188). This painting is the epitome of feminist art because not only exposes a uniquely female experience, but its graphic nature makes it a striking denouncement of the objectification of women’s bodies through art.

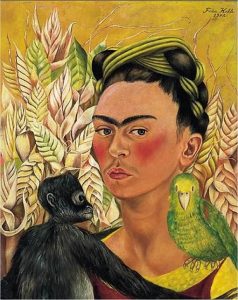

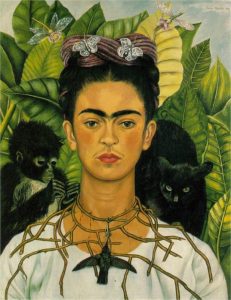

Thanks to the freedom of expression Frida experienced, her art was influential and provocative in many other ways beyond the reclamation of the female body. Her influence is most notably evidenced by her surge in popularity in recent decades. In 1995, her painting Self-Portrait with a Monkey and a Parrot (Fig. 5) sold for $3.2 million, the highest price ever paid for a Latin-American work of art and the second-highest amount paid for a women artist (Collins). Frida’s popularity likely stems from the revolutionary nature of her art and life, and the feminist sentiments they inspire. In the heavily male dominated artistic narrative of post-revolutionary Mexico, Frida’s art offers a refreshing female perspective. Perhaps the most outwardly feminist theme of her art is the way she questions societal gender roles through sexual ambiguity in her self-portraits. For example, in her famous Self-Portrait with a Monkey and a Parrot (Fig. 5), Frida paints herself with obvious male features, such as a unibrow and mustache. Many of Frida’s other self-portraits also depict her with masculine features such Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair (Fig. 6) in which Frida is dressed in a man’s suit and boyish haircut after having cut off her long hair, a popular sign of Mexican womanhood and female beauty (Bakewell 169). Frida is often charged with exaggerating her facial hairs and masculine features in many of her other self-portraits in order to blur the line between male and female, as additionally evidenced by Self Portrait with a Necklace and a Hummingbird (Fig. 7) and Fulang Chang and I (Fig. 8) (Bakewell 169). In doing so, she not only attacks the patriarchy but also redefines beauty. As Carlos Fuentes eloquently puts it, “The manner of conceiving beauty as truth and self-knowledge…is Kahlo’s great legacy to the women of an increasing faceless, anonymous planet, where only the ‘photogenic’ or ‘shocking’, as seen on the screens, merits our vision” (Fuentes 17). Kahlo does not abide by conventional beauty standards, but this unconventional appearance and defiance is exactly what makes her beautiful. With a legacy of redefining beauty in the 21st century, her art inarguably makes the public question accepted realities, proving women’s ability to catalyze change in society.

The feminist movement took place in three distinct waves. Frida Kahlo lived during the “first wave” of feminist movement and died before the “second wave” occurred. The first wave of the movement occurred roughly from the 1830s to the early 1900’s and was concerned mostly with women’s suffrage, a goal that was realized in the United States in 1920 with the 19th amendment. Surprisingly, women in Mexico only gained the right to vote in 1953 for local elections and for national elections in 1958 meaning that Frida never had the opportunity to vote during her lifetime. Frida’s active participation in the Communist party demonstrated her defiance of the political restrictions that were placed on her as a woman her and her determination to inspire change in her lifetime, which was another inspirational facet of Frida’s feminist character. The “second wave” of the feminist movement took place between the 1960’s and the 1980’s and was characterized by the fight for gender equality in the workplace, as well as for sexuality, family and reproductive rights (Dorey-Stein). More specifically, the Chicana Feminist movement was born during this time within the context of the larger Chicano movement, which fought for the rights of Mexican Americans. This subset of the feminist movement was uniquely concerned with “Chicana feminists struggle to gain equal status in the male-dominated nationalist movements and in American society” (Garcia 220). After her death in 1954, Frida became an icon of Chicana movement, because Kahlo’s Mexican identity along with her defiant and politically active life, embodied the ideals Chicanas were fighting for. Frida also embodied the larger ideals of the second wave in many ways. She fought for gender equality in the workplace in the way she fearlessly produced art in a male-dominated artistic arena (as mentioned above). Furthermore, she fought for sexual liberation in the way she blurred the line between male and female in her iconic self-portraits and engaged in relationships with both men and women. Considering these parallels between the life and work of Frida and the goals of the second wave of feminism, it is not surprise that the surge in Frida’s popularity began during this time.

The third wave of Feminism began in the 1990’s and continues through the present. This wave builds upon the legal rights and protections gained during the first and second waves of feminist struggle and aims to finish the perceived unfinished work of the second wave, including “redefine[ing] the ideas, words, and media that have transmitted ideas about womanhood, gender, beauty, sexuality, femininity, and masculinity, among other things” (Burkett & Brunell). Unsurprisingly, Frida Kahlo is also an icon of this wave, alongside other notable female figures such as Madonna, Beyoncé, and Lena Dunham. Beyond the feminist nature of Frida’s life and work, the most recent surge in her popularity is attributed to the publication of her biography by Hayden Herrera in 1983 and the making of multiple major motion pictures of her life.

There are many obvious reasons for Frida’s explosion in popularity in recent decades in relation to the feminist movement, however there might also be some less-obvious underlying psychological reasons women of today are particularly enamored with her. According to the Kirk Varnedoe, the chief curator for the Museum of Modern Art in New York city, “[Frida] clicks with today’s sensibilities- her psycho-obsessive concern with her herself, her creation of a personal alternative world carry a voltage… . [and] she fits well with the odd, androgynous hormonal chemistry of our particular epoch” (Collins). The obsessive concern with our personal identities and public perception is particularly evident in the rise of social media. This self-obsession is manifested in Frida’s self-portraits and our modern-day Instagram, Facebook, and Snapchat accounts. Where Frida differs from the modern users of social media is the way she depicts struggle alongside her strength. In a society where we spend a significant portion of our time attempting to construct a perfect and seamless public image of ourselves, we can take note from Frida’s self-portraits which offer us an autobiography in paint that depicts an unavoidable and universal struggle, defined by a resonating acknowledgement that we are not alone in our suffering.

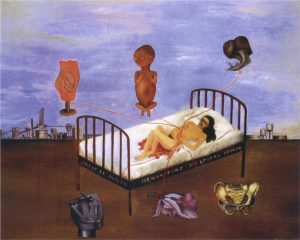

Frida’s life was characterized by suffering, and thus, so was her art. According to her biographer Hayden Herrera, one of “the qualities that marked Kahlo as a person and as a painter [was] her gallantry and indomitable alegría in the face of physical suffering” (Herrera x). Furthermore, her depiction of pain and suffering from a uniquely women’s perspective was unprecedented for the time, making her not only revolutionary, but also feminist. The uniquely feminine issues that Frida depicted in her art range from miscarriages to divorce and more. Her piece of work that most obviously depicts the theme of miscarriage is Henry Ford Hospital (Fig. 9). This piece comes from Frida’s actual experience of having a dangerous miscarriage while living in Detroit in 1932. The piece shows Frida lying naked in a hospital bed bleeding, holding six vein-like ribbons that are attached to different objects floating around the frame. The objects include a pelvis bone, a snail, a piece of machinery, a dying flower, and perhaps most strikingly a male fetus. The flower is evocative of the famous flower drawings of one of Frida’s contemporary feminist artists Georgia O’Keeffe. O’Keefe is famous for her large-scale flower paintings that symbolized female genitalia. This was Frida’s first piece of iconic art, and marked a transition in her painting style. As noted by her husband Diego Rivera at the time, after the miscarriage “Frida began work on a series of masterpieces which had no precedent in the history of art-paintings which exalted the feminine qualities of endurance of truth, reality, cruelty, and suffering” (Herrera 144). Miscarriages are undoubtedly one of the most haunting experiences a woman can experience, and this reality is masterfully depicted in this piece. To this day, miscarriages are still considered a taboo and deeply personal topic and Frida’s willingness to depict the experience of having one so graphically yet beautifully is likely what makes this piece so gripping and iconic. This piece demonstrates Frida’s unparalleled ability to encapsulate often inexplicable female realities in her work.

Another type of suffering that inspires many of Frida’s pieces is the pain of heartbreak. Frida was famous for saying that she suffered two accidents during her lifetime, the tram accident that would leave her crippled for the rest of her life, and her love affair with Diego Rivera, claiming that he was the worse of the two (Malkin). Diego Rivera and Frida’s love affair is one of the most iconic modern love stories, characterized by fervent passion, affairs, and heartbreak. This pain of heartbreak is depicted in many of her pieces, notably in what is probably her most famous piece The Two Fridas (Fig. 10), drawn in the wake of her divorce with Rivera in 1939. In this painting, two Frida figures sit side by side on a bench holding hands. The Frida figure on the left is dressed in a white Victorian dress and the one on the right is dressed in traditional Mexican dress. Both Fridas have exposed hearts- a literal device Frida often uses to show pain in love (Herrera 278). Both Fridas are connected by a vein between their hearts. The one on the left is also pictured with another vein coming out of her heart that appears to be severed by scissors that she is holding with blood flowing from the vein onto her white dress. This appears to be a reference to her recent severance of her relationship with Diego and the pain it has caused her heart. The Frida on the right is also holding a miniature portrait of Rivera as a child, another reference to her lost husband. In the background of the image there is a grey and black stormy sky, another reminder of the turbulence in Frida’s life caused by the divorce. The Two Fridas demonstrates that Frida’s only companion is herself after the divorce, and “the doubling of herself deepens the chill of loneliness” (Herrera 279). Loneliness and heartbreak is a universal experience that transcends time periods and cultures, making this piece resonate with many people, especially women who are stuck in relationships defined by the expectation of remaining faithful wives who are dependent on philandering husbands. This piece articulates the pain of divorce, but also demonstrates the resiliency of survivors, as Frida’s unavoidable gaze commands your attention and assures you of her strength.

Beyond her tragic life story and the “unmistakable power of her face on a T-Shirt” (Malkin), Frida’s acclaimed artwork is still the defining aspect of her life that makes her one of the most iconic feminist artists of recent decades. Her ability to articulate the universal sentiment of suffering in her art is what resonates with the viewer and makes her unforgettable. As we enter a time period where feminism is no longer an exclusively women’s movement, but one supported by anyone who identifies with being oppressed and wants to end the senseless oppression of women, the messages in Frida’s paintings become more and more universal and applicable. The work of feminist movement is not over as evidenced by the recent historical Women’s March on Washington and the troubling fact that women continue to only make eighty cents to the men’s dollar (National Committee on Pay Equity). The life and work of Frida Kahlo can continue to be a source of hope and inspiration as we march defiantly and decidedly forward through the next four years and beyond.