Research Paper

The Failure of Rivera and Siqueiros, Communism in the Mexican Muralist Movement

The Mexican Muralist movement intended to create a new national identity that celebrated Mexico’s precolonial past as well as its mestizo identity. Through their public art, the most influential artists of the movement, Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco, instilled in the Mexican population a new vision for the future of the country. Although these artists were deeply committed to the movement and its ideals, they were also heavily influenced by their political views. Rivera and Siqueiros in particular, were strong supporters of the communist movement, which can be seen across their work. There are numerous examples of communist propaganda in their murals, and one Rivera’s most famous murals, which I will consider in this paper, is the mural that he first painted at Rockefeller Center in 1933, “Man at Crossroads”. Murals such as “Man at Crossroads”, indicate that there was an attempt by these artists to promote Communism across Mexico and even abroad. Despite Rivera’s and Siqueiros’ attempt to promote the communist movement in Mexico through their murals and through their activism, the new nature of Mexican politics and the consolidation of the Mexican Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) that arose after the Mexican Revolution, prevented communism from ever gaining significant influence in Mexican society.

Even before the communist movement became a political entity, there were signs that communist ideals could gain influence in Mexico. The Bolshevik Revolution, which was occurring concurrently with the Mexican Revolution, had a significant impact on the Mexican people. Labor organizations, artisans, and intellectuals identified with the ideals of the Russian revolution, and saw it as having the same goals as their own revolution. In fact, Emiliano Zapata wrote to his friend Genaro Amezcua, “we would gain a lot, human justice would gain a lot, if all the peoples of our America and all the nations of old Europe were to understand that the cause of Revolutionary Mexico and the cause of Russia are and represent the supreme interests of all the oppressed peoples” (Spenser, 36). Finally, on September 25, 1919, extreme left Socialist held a congress in Mexico City and founded the Partido Comunista Mexicano (PCM). Just three years later, the communist party fell under the control of artists and intellectuals, led by Diego Rivera and David Alfaro Siqueiros. The two artists soon became active leaders of the PCM and their publication El Machete became the official organ of the Party (Schmitt, 10). Throughout the rest of their careers, Rivera and Siqueiros continued to be actively involved with the Party and the communist movement, while their work became increasingly more politicized.

Figure 1: Cover of “El Machete”

During the initial years of the communist movement, Rivera and Siqueiros quickly became influential figures of the Communist Party. By the end of 1923, the painters who belonged to the PCM, created the Union of Technical Work

ers, Painters, and Sculptures, with Siqueiros as its general secretary and Rivera as its secretary of the interior (Stein, 40). The creation of the union led to the political awakening of the artists, which in turn resulted in vastly different murals. At the beginning of the muralist movement, the artists simply wanted to create “murals for the people”, public art; however, after the creation of the Union, they wanted to create murals as well as instilling their ideals to the people. Siqueiros depicted his first “worker’s struggles” and Rivera began painting the exploitation of the peasants by the ruling class (Stein, 41). Apart from conveying their message through their murals, the Union published the controversial revolutionary newspaper, “El Machete”. Rivera and Siqueiros were members of the executive committee, contributed drawings, and even wrote articles under pseudonyms. El Machete contained numerous communist elements, such as the star, the hammer, and the sickle on the header, as well as including explosive political material. Siqueiros and Rivera understood the power of the printed word, which is why they developed El Machete as an ideological platform that would later become an elemental part of the PCM (Stein, 41).

Rivera’s work was significantly influenced by his political views, and his fame allowed him to move up the ranks of the Communist party; however, his dedication to the party and to the movement as a whole varied throughout the years depending of what was more convenient to him. Rivera officially joined the PCM in 1922 after his return from Europe. Because of his fame, his age, and his oratory skills, Rivera quickly became a leader of the party and was elected to the Executive Committee in 1923 (Hamill, 95-96). Rivera was also elected the president of the Union of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptures, but he had almost no time for union affairs. Although Rivera had a tendency to make a grand gesture for the union such as volunteering for a public role, most of the hard work fell to Siqueiros (Hamill, 96-97). Rivera’s visit to Russia in 1927 further decreased his commitment to the communist movement back home (especially Stalinism), since he became disillusioned with the growing authoritarianism of the Soviet government (Richardson, 50). His contempt for Stalinism was based on his visit to Moscow, but it also had a practical reason: he needed money (Hamill, 142). His involvement with the communist movement therefore, became characterized by practicality and convenience. Rivera was a very astute politician, in the sense that he understood that power was provisional. Diego learned to worry not about the future development of his work, but the future of the people who signed the checks (Hamill, 98).

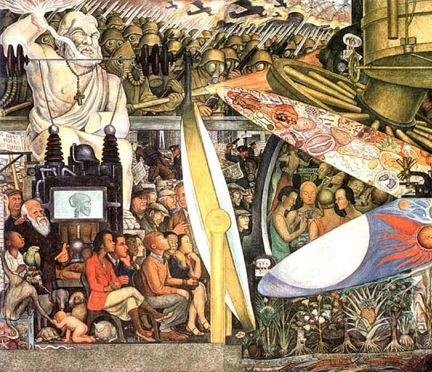

In 1932, Diego Rivera was commissioned to create what is arguably his most famous and controversial fresco, Man at the Crossroads at Rockefeller Center. During this time, the United States was facing a threat from communist ideas that appealed to the working class, which had been severely affected by the Great Depression. Communism was viewed by many Americans as a serious threat to capitalism and their current way of life. Rivera’s mural caused so much debate because of his use of numerous communist elements, especially a portrait of Soviet revolutionary, Vladimir Lenin. Although Rockefeller was a strong supporter of Rivera, the inclusion of Lenin presented a significant legal problem. Lenin’s insertion into the mural was a drastic move from the original plan since he doesn’t appear anywhere in the approved sketch. In addition, Rockefeller also had a practical consideration that was more important than Rivera’s violation of his contract. Rockefeller was anxious to rent the new offices of his building to capitalist tenants who would not be happy to see Lenin every time they walked in for work. Ultimately, Rivera refused to remove the portrait because he perceived Lenin as the “supreme type of labor leader”, who provided a sentimental alternative to the brutality of Stalin (Hamill, 165-166). Rivera’s insistence eventually forced Rockefeller to order the destruction of the mural; however, not long after the mural was removed, the Mexican government commissioned Rivera to recreate Man at the Crossroads in the Palace of Fine Arts in Mexico City.

Due to its critical nature, Man at the Crossroads was bound to encounter both praise and criticism. The fresco is characterized by having two polarizing sides. On the left side of the panel, Rivera included images of threatening looking soldiers that are ready to attack, a group of policemen assaulting protestors, wealthy individuals indulging in frivolous habits, and even venereal disease microbes. On the right side of the panel, Rivera included images of peaceful protestors waving red communist flags, and he even included an image of Vladimir Lenin holding hands with several workers (Paquette, 144). When these two sides are put together, it is clear that Rivera intended to present the “evil” capitalists, in contrast with the “enlightened” communists. Through this dramatic contrast of scenes, Rivera comparedclass inequities and the oppression of labor in the U.S. capitalist system with what he believed were the virtues of communism. References to warfare, unfair treatment of workers, and sexually promiscuous activity on the left sharply juxtapose the images on the right of social stability, a strong work ethic, righteous behavior, and physical well-being (Paquette, 146). These two sides are in clear tension with one another, constituting a “provocatively bipolar view of U.S. capitalism and Soviet communism” (Paquette, 144).

Although both Rivera and Siqueiros were both active communists, the latter was the more ardent supporter of the movement, showing a relentless effort to promote communist ideals that often times, especially in the 1920s and 1930s, far overshadowed his art. As the Union continued to publish El Machete and as their art became increasingly more politicized, the students of the Colegio San Ildefonso, the place where they worked in the initial stages of the muralist movement, became more belligerent and violent. Students and professors of the Preparatoria were so disgusted by the “blasphemous” murals, that there was a significant altercation in which a group of protestors attempted to destroy one of Siqueiros’ murals. The artist defended himself with a gun that he was carrying, and soldiers had to intervene in order to restore order (Stein, 49). This altercation, together with the resignation of Vasconcelos, resulted in an increasingly public resistance against the artists’ movement. Seeing that opposition towards their cause would only increase, Rivera moved closer to the government side, withdrew his funding of the newspaper, and refused to sign the union’s protest condemning the student attacks. To make things worse, Vasconcelos’ replacement as Minister of Education, José Manuel Puig Casauranc presented the members of El Sindicato with an ultimatum: continue to publish El Machete, and your contracts for mural painting will be suspended. Diego Rivera opted to continue painting his murals, while Siqueiros maintained his position of supporting El Machete (Stein, 50). For the next few years, Siqueiros moved away from painting, focusing on promoting his revolution. He even once said that “from the year 1924 to 1930, [he] did not once think about painting” (Stein, 55). Siqueiros instead addressed mass rallies, initiated the convening of the National Peasants Congress of the League of Agrarian Communities, and became a leader of the PCM (Stein 54-55, 57). Siqueiros eventually returned to painting, but in the meantime, he proved his loyalty to the workers’ cause through his total commitment to his political beliefs.

After being deeply involved with political activism for several years, in 1937 Siqueiros was commissioned to lead the creation of a mural for the Mexican Electricians’ Syndicate (SME) in Mexico City, allowing him to return to promoting his communist ideals through his art. From the beginning, this project was guided by communist ideology not only in its thematic orientation, but also its process (Jolly, 131). Siqueiros first accepted the commission for this mural on the condition that he would be allowed to organize a team of artists to join him, which would later be known as the International Team of Plastic Artists. The group of artists called themselves a “collective” and by doing so, they assigned themselves an “ideological charge, linking [them] to an approach to art-making associated with the Left during the 1930s and opposing bourgeois individualism” (Jolly, 137). Regarding the mural’s content, the syndicate directors originally intended the mural to focus on the electrical industry; however, the muralists were able to convince a significant number of electrical workers that it was critical to address anti-fascist struggle. With the support of the workers and several communist-sympathizing directors, Siqueiros and his team negotiated the expansion of the original conception of the mural’s themes to also include international politics. The first themes chosen by the collective were fascism, imperialism and war, and soon afterwards, capitalism became the overarching concept of the mural (Jolly, 99-100).

Figure 5 Siqueiros and the International Team of Graphic Artists. Mexican Electricians’ Syndicate Mural

In the end, the vision of the collective prevailed, with a mural that included a cinematic montage describing how fascism emerged out of capitalism and its generation of imperialism and war, and a condensed depiction of the production of electricity (Jolly, 98). The mural was designed to be viewed sequentially by a moving spectator. On the left side of the panel, there is a prominent figure with a parrot’s head representing Fascism and demagogy, addressing a group of protesters and groups of soldiers, which include Nazi Stormtroopers and Mussolini’s Blackshirts (Jolly, 104). These soldiers and protesters are rallying on the steps of a classical building that is on fire. The classical style of the building and the inscription in the pediment, “Liberté, Equalité, Fraternité”, are symbols of democracy. The inscription has a moneybag superimposed over it, suggesting that democracy has been tainted by capitalism (Jolly, 104). The torch held by the demagogue as well as the army by the building, reveal that this wall in its entirety represents the “self-destruction of capitalist democracy through its generation of Fascism” (Jolly, 105). The center wall presents a chaotic scene that is dominated by a giant metal object with golden coins pouring out from its inside, again representing capitalism. The metal figure, together with the chaotic scene in the background, once again suggests the destructive effects of capitalism. Finally, the right side of the wall introduces a very interesting figure that contrasts the dark nature of the rest of the mural. As the viewer moves up the stairs, he/she will see a large image of a man with a white shirt, carrying a gun and a red flag. The red flag suggest that this man is a communist, and he represents the revolutionary force that is needed to confront the “imperialist war machine” (Jolly, 106).

Despite Siqueiros’ and Rivera’s attempt to promote Communism in Mexico through their political activism and murals, the tight control of the governing party in the country prevented communism from ever gaining significant influence in Mexico. In 1928, a pivotal political crisis occurred in Mexico when the revolutionary hero Álvaro Obregón was assassinated. The outgoing president, Plutarco Elías Calles, attempted to prevent yet another violent dispute over the presidency in the aftermath of Obregón’s assassination; however, Calles knew that he could not take reigns over the presidency again without causing an armed conflict against his political rivals. In order to ensure a peaceful transition of power, Calles created a political party as a means of creating a process to designate a new presidential candidate, while also containing the opposition. Calles’ efforts resulted in the formation of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PNR) in 1929. For the next six years, a period known as El Maximato dominated the country, with Calles holding significant political influence through his manipulation of the PNR. The Party consolidated its power during this period, with Calles ruling over the different groups and political leaders that sought influence within the government. The PNR thus, became a mechanism for deciding who would be the candidates for public office, from congressional seats all the way to the presidency. Through this process of consolidation of power, the PNR essentially distributed political power among competing groups in order to avoid disagreements that could lead to instability (Saragoza et al., 501). Through the years, the PNR evolved into what is now the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), which governed the country for over 70 consecutive years and is the current the governing party in Mexico.

Although the PNR was willing to accept artists such as Rivera and Siqueiros to promote radical ideas through their art when the party did not feel threatened, actions that could jeopardize the current balance of power was never tolerated. In 1929 for example, the economic recession of the United States was the catalyst to a disastrous phase of the Communist movement. Under Generals Aguirre and Escobar, a full-scale revolt against the government was being planned. The PCM interpreted this imminent confrontation as the “final phase in the internal struggles and contradictions of the Mexican Bourgeoisie and their opportunity to seize power” (Schmitt, 15). The PCM planned to support Calles in his efforts to suppress the revolt and then proceed with an attack on Calles to overturn the government. However, their plan completely backfired when the Calles learned the details of the PCM’s plan from defectors. When the revolt was suppressed, the PCM was made illegal, party members were jailed, and El Machete was closed (Hamill, 138). The next five years resulted in a complete prosecution of the communist movement in Mexico, exemplifying the new party’s ruthlessness against its rivals when the balance of power was threatened.

The rise to power of Lázaro Cárdenas to power in 1934 provides a contrasting view of how the Mexican government, and more specifically the PNR, allowed certain forms of dissent as long as their power was not affected. Rivera’s recreation of “Man at Crossroads” in the palace of fine arts in Mexico City, exemplifies the PNR’s willingness to accept radical political views being promoted if certain elements aligned with their own policies. The party introduced its “Six-Year Plan” in 1933, outlining their vision for the future of the country. The plan asserted the PNR as a

workers’ party and declared that socialist as well as labor issues would be the government’s priority (Paquette, 147). After Rivera’s mural was destroyed in 1934, the Mexican government was willing to commission Rivera to recreate his work, since “Man at Crossroads” aligned in many ways to PNR policy items. For example, Rivera’s contrasting images of warfare and peace resonated with the party’s calls in the Six-year Plan for “peaceful resolution of differences between nations”. The portrait of Lenin with an industrial laborer, a worker, and a soldier served a particularly useful purpose, since the government was attempting to instill sentiments of brotherhood and solidarity in their students (Paquette, 148). Cárdenas’ term as president also saw a reconciliation between the government and the PCM, which had been harshly persecuted since 1929. In fact, one of Cárdenas’ first acts after his inauguration was to formally stop the attack on Communists and to free Communists leaders that had been imprisoned in the Islas Marías (Schmitt, 16). Despite the public appearance of reconciliation with the Communist party, which served to accentuate Cárdenas’ socialist policies, the president acted swiftly to prevent the PCM from gaining any real power. Cárdenas never accepted the Communists in a government coalition, refused to let them incorporate into the PRN, and did not allow them to form a significant bloc in Congress (Schmitt, preface vi). The PRN was willing to allow radical ideas, such as Communism, to be promoted through mediums like art, but carefully excluded the PCM from achieving any type of political power that could alter the status quo.

Although Siqueiros and Rivera were both deeply influenced by their political views, their personal experiences with the Communist movement were significantly different. Diego Rivera had a turbulent relationship with the Communist party in Mexico, mainly because his actions proved that he always prioritized his art. Siqueiros was a passionate supporter of the movement, tirelessly working to promote Communist ideals through his art and through political activism. The disparity between Rivera’s and Siqueiros’ involvement with Communism is just one example of how vastly different these two artists were. Both artists disagreed on so many different issues, ranging from art to politics, that a rivalry between the two emerged. Siqueiros publicly attacked Rivera’s art claiming it was “retarded” and “Incapable of working outside the traditional fresco” (Anreus, 49). Rivera would respond to this criticism by claiming that Siqueiros was a “Stalinist.. and an enemy of both plurality in the arts and permanent revolution in politics” (Anreus, 49). Evidence of their conflicting ideologies can be seen throughout their careers with events such as Rivera’s hosting of Leon Trotsky when he received asylum in Mexico, and later Siqueiros’ involvement in an attempt to assassinate Trotsky. In the end despite their differences, Siqueiros payed homage to Rivera by attending his funeral in a tradition that started when José Clemente Orozco died years earlier. Ultimately, Rivera and Siqueiros had a deep impact in Mexico due to their work during the Mexican Muralist movement and their political activism, even if they eventually failed to propagate their Communist views.

Works Cited

- Anreus, Alejandro, Leonard Folgarait, and Robin Adèle Greeley. “Los Tres Grandes: Ideologies and Styles.” Mexican Muralism: A Critical History. Berkeley: U of California, 2012. 37-54. Print.

This is a reliable source since it was written by art professors that are qualified to write about the topic. This section of the book gave me information about the different ideologies of Rivera and Siqueiros and how these differences led to a rivalry. I used this source for my concluding paragraph.

- Hamill, Pete, and Diego Rivera. Diego Rivera. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1999. Print.

This biography of Rivera was a great source to understand his involvement with the communist movement in Mexico. It reveals how his commitment to the movement depended on what was more convenient for him. This book is written by a respected journalist, novelist, essayist, editor and educator, making it a reliable source.

- Jolly, Jennifer. “Art of the Collective: David Alfaro Siqueiros, Josep Renau and Their Collaboration at the Mexican Electricians’ Syndicate.” Oxford Art Journal, vol. 31, no. 1, 2008, pp. 131–151., jstor.org/stable/20108009.

This is a reliable source since it was written by a professor from Ithaca College that specializes on the Mexican Muralists. This source gave me detailed information about the ideologies behind Siqueiros’ mural at the Mexican Electricians’ Syndicate.

- Jolly, Jennifer. “Two Narratives in Siqueiros’ Mural for the Mexican Electricians’ Syndicate.” Revistas UNAM 8 (2005): 97-116. Web. http://www.revistas.unam.mx/index.php/cronicas/article/view/17251/16429.

This is a reliable source since it’s written by the same author as my previous source. This article have me more information about how Siqueiros’ mural could be interpreted.

- Paquette, Catha. “Revolutionary” Ideologies and Discursive Struggle: Diego Rivera’s 1934 Mural Commission at the Palace of Fine Arts.” Latin Americanist, vol. 54, no. 4, Dec. 2010, pp. 143-162. EBSCOhost, doi:10.1111/j.1557-203X.2010.01095.x.

This is a reliable source since the author is a professor of Art at the California State University in Long Beach. The source presented a detailed description of Rivera’s mural in Rockefeller Center and explains why the Mexican government decided to commission of the mural.

- Richardson, William. “The Dilemmas of a Communist Artist: Diego Rivera in Moscow, 1927-1928.” Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos, vol. 3, no. 1, 1987, pp. 49–69. jstor.org/stable/4617031.

This article gives a history of Rivera’s involvement with the communist movement. This is a reliable source since it was published in a peer reviewed article that focuses on Mexican studies. This source reveals how Rivera became disillusioned by the communist movement after he witnessed the growing authoritarianism in the USSR during his visit to Moscow.

- Saragoza, Alex, Ana Paula. Ambrosi, and Silvia D. Zárate. “Partido Revolucionario Institucional.” Mexico Today: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2012. 501. Print.

This is a reliable source since I obtained this article from a published Encyclopedia written by professors in Latino Studies. I used this source to get background information about el PRI and its origins, to understand how they were able to prevent communism from ever gaining a significant influence.

- Schmitt, Karl M. Communism in Mexico: A Study in Political Frustration. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1965. Print.

This book traces the history of the communist movement in Mexico. This is a reliable source since its author is very qualified on the topic. Dr. Schmitt has a doctorate degree from the University of Pennsylvania, has worked as a government and history professor, and even worked for the US department of state. This book was my main source that helped me understand the communist movement in Mexico.

- Spenser, Daniela. Stumbling Its Way Through Mexico: The Early Years of the Communist International. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2011. Print.

This is a reliable source since its author has been a researcher at the Centro de Inverstigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social in Mexico City since 1980, making her very qualified to write about the topic. This source gave me valuable background information on the communist movement in Mexico.

- Stein, Philip, and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Siqueiros his life and works. New York: International Publishers, 1994. Print.

This biography of Siqueiros was a great source to understand his involvement with the communist movement in Mexico as well as how his art was influenced by his political ideas. This book was written by an American muralist that lived in Mexico and worked with Siqueiros, making it a reliable source.