Operation Homecoming and Just Compensation

Under the trusteeship we have come to know and respect you as members of our American family, and now, as happens to all families, members grow up and leave home. I want you to know that we wish you all the best as you assume full responsibility for your domestic affairs and foreign relations, as you chart your own course for economic development, and as you take up your new status in the world as a sovereign nation. But you will always be family to us.

– President Ronald Reagan, October 21, 1983, on the Compact of Free Association

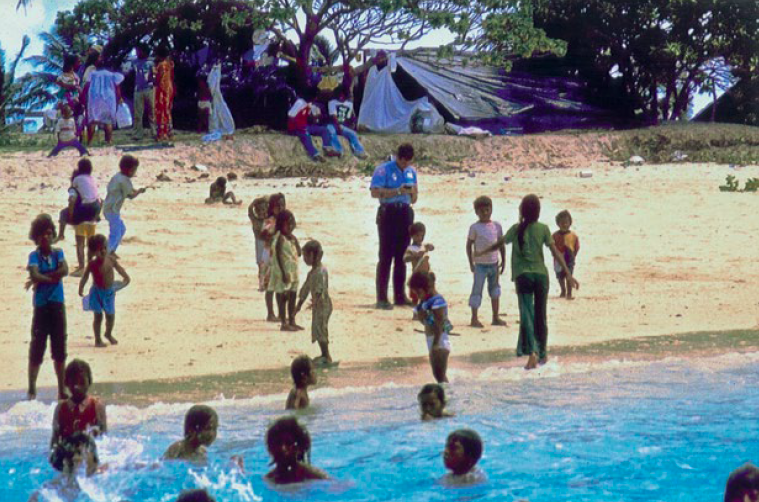

In May 1982 Marshallese sailed from Ebeye to Kwajalein. Except this time they did not leave at the end of the day. Earlier that month, the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) had finished negotiating the Compact of Free Association with the United States, which would grant sovereignty to the Marshall Islands and end the United States trusteeship. Against the wishes of Kwajalein’s native inhabitants, the terms of the treaty included a 50-year lease of Kwajalein Island and no stipulations for improving the US Army’s treatment of Marshallese workers. Furious that “independence” from the United States perpetuated American control over their islands, displaced Kwajalein landowners staged an occupation protest on the clean, sandy beaches of the military base. (In Marshallese culture extended families are considered to share ‘land rights’ and the product of the land is split amongst irooj chiefs, alap clan heads, and rijerbal commoners/workers. “Landowner” thus reflects a Western ideology).[1] For four months the Marshallese occupied their island homeland while enduring harassment and threats from the US Army. Finally, in October 1982 the Pentagon decided to reopen discussions with the RMI. The Marshallese President Amata Kubua used eminent domain to seize control of Kwajalein and negotiate without the landowners. The new agreement returned six islands to the Marshallese, created a ten million dollar capital improvement fund, and reduced the lease from fifty to thirty years. With these concessions from the United States, the protesters returned to Ebeye Island.[2]

The protesters, however, had failed to achieve their ultimate goal: repossession of their homeland. The Compact of Free Association established the precedent for landowner compensation. Instead of directly dealing with landowners, the United States negotiates the terms of their lease as an international agreement with the RMI. Distribution of that money is then a domestic issue between the RMI and the landowners. This model, however, disempowers landowners. For example, in the 2003 renegotiations of the Contract, the final agreement between the United States and RMI offered landowners $15 million a year, less than half the amount they wanted. Even though the landowners refused to sign the agreement for eight years, the United States continued to use Kwajalein since they had signed off with the RMI. The landowners’ protests fell on deaf ears.

This landowner compensation arrangement is a settler move to innocence. By exclusively negotiating with the RMI for the Compact of Free Association, the United States could preserve the illusion they were fully liberating the Marshall Islands. Domestic disputes between the RMI and landowners thus did not impede their decolonial mission. Americans could treasure their “special relationship” with the Marshallese while continuing to exploit their land.

Moreover, just compensation for land is a colonial concept in itself because it permits the United States to stay. The flow of dollars to the RMI and landowners give them a stake in American presence. In “Still in the Blood: Gendered Histories of Race, Law, and Science in Day v. Apoliona,” Maile Arvin argues that when five Native Hawaiian men sued the Office of Hawaiian Affairs for not restricting their services to the blood-quantum definition of indigeneity, these men “called the law on themselves” and perpetuated Western notions of whiteness.[3] Similarly, by arguing over how much money is just compensation for leasing Kwajalein land, the RMI and Marshallese landowners internalize Western notions of land use and normalize the United States’ presence. As Johnsay Riklon, a Marshallese lawyer who was deeply involved in Operation Homecoming, reflected, “Money is so powerful. Each time the US just gives us a little more money to stop asking for our land back and so we just go away. It’s a sad situation.”[4] Moreover, not all residents of Ebeye are Kwajalein landowners. The nuclear refugees have no land claims on Kwajalein and thus are excluded from debates over compensation. When Marshallese advocacy efforts focus on the question of how much, decolonization is taken of the table.

[1] Greg Dvorak, “Detouring Kwajalein: At Home Between Coral and Concrete in the Marshall Islands,” in Touring Pacific Cultures, ed. Kalissa Alexeyeff and John Taylor (Acton, Australia: ANU Press, 2016), 118.

[2] Jane Dibblin, Day of Two Suns: U.S. Nuclear Testing and the Pacific Islanders (New York: New Amsterdam Books, 1988), 92-106.

[3] Maile Arvin, “Still in the Blood: Gendered Histories of Race, Law, and Science in Day v. Apoliona,” American Quarterly 67, no. 3 (2015): 681-703.

[4] Jane Dibblin, Day of Two Suns: U.S. Nuclear Testing and the Pacific Islanders (New York: New Amsterdam Books, 1988), 105.